LondonJazz has a review of Rhythmica’s recent concert at the QEH here. And links to some videos are here on Rhythmica’s pages. Be delighted, be very delighted!

Next concert on the Rhythmica Wake-up-the-Nation tour is in Cambridge on 13 March 2011 at Clare Jazz, Clare Cellars, Memorial Court, Queen’s Road, Cambridge CB3 9AJ.

Archive for the ‘Music’ Category

Page 9 of 13

Cocktails with Rhythmica

Another superb gig from Rhythmica, this time in the Cafe of Foyle’s Bookshop in London. After last weekend’s wake-up call in Southport, tonight’s gig was at a more civilized hour. But the pace and the musical skill and the serious intent were just the same – anyone expecting easy-listening, cocktail-bar music was in for a shock!

With about 75 people present, it was standing room only. Standing at the back, I found Peter Edwards’ piano hard to hear – maybe it was not amplified, or not sufficiently. I enjoyed again bass Peter Randall’s solo in Parallel, a solo which seemed to have more coherence tonight, or perhaps I understood the motifs and their development better this time round. Andy Chapman on drums provided solid support for the odd time signatures, and I noticed again the frequent rhythmic coupling and tripling he did with Randall’s bass and Edwards’ piano.

I was also impressed by Mark Crown’s superfast bop trumpet solo on Herbie Hancock’s The Sorcerer. But the man of the match tonight was undoubtedly stand-in tenor sax player, Binker Golding, whose blistering, vein-popping solo on the same number had the audience up in a standing ovation when he ended. Even the two Dutch women near me who talked through the entire set were quiet for this, although they still didn’t look at the stage.

As best I recall, the order of songs was:

- Time Machine (Audu)

- Anthem (Edwards)

- Parallel (Joe Harriott)

- Turner’s Dream (Crown)

- Triple Threat (Edwards)

- The Sorcerer (Hancock)

- Blind Man’s Stomp (Golding).

Can’t wait to hear these guys again!

UPDATE (2011-02-18): A video of Binker’s blistering solo is here, and photos of the gig here.

Breakfast with Rhythmica

Earlier today I caught a rainy, late morning gig by Rhythmica as part of the Southport Jazz on a Winter’s Weekend Festival. The quintet comprises Mark Crown on trumpet, Peter Edwards piano, Peter Randall double bass, Andy Chapman drums, and Zem Audu on sax. Audu was absent today, his place taken by Binker Golding on tenor sax. There were perhaps 150 people in the audience, with only a handful looking younger than 50. Maybe everyone younger was still asleep.

What a way to wake up! From the first three bars of the first number – Time Machine – you knew these guys were serious – they were people to be reckoned with. The piece was in 11/4 (or perhaps one bar in 3 beats to every two bars in 4), and they were extremely together! Piano and bass were in close unison for an ostinato bass line, trumpet and tenor sax together in similar unison for the melody. And everyone – all 5 – in very tight formation. The close co-ordination was evident throughout the morning, with the players grouping mostly as for Time Machine.

The use of trumpet and sax together, sometimes in unison, sometimes playing seconds and thirds (especially at the ends of unison phrases), with the piano riffing between phrases, as if commenting from the sidelines on the melody, is a feature of Wynton Marsalis’ compositions, and before him, of Wayne Shorter and others in the early 60s. This produces what I find is a very attractive sound, and Rhythmica did it very well. Anthem was in this vein. Sometimes also the bass and drums would double (as in Mr JJ), and just once we also heard trumpet, sax and piano play unison/thirds choruses together, in the aptly named Triple Threat. And for the final chorus of Solace, Crown’s trumpet played long-held falling fifths underneath everyone else’s bop gyrations; these were just sublime.

In a lineup of excellent performers, the standout for me was bass player Peter Randall – he was fast, agile, and with lots of interesting walking lines – and using all five fingers to stop strings in the high registers. But we only heard him solo once (in Parallel) – it would be good to hear more of him.

As best I recall, the order of songs was as follows:

Set 1:

- Time Machine (written by Audu)

- Anthem (Edwards)

- Delfeayo’s Dilemma (Wynton Marsalis)

- Turner’s Dream (Crown)

- Mr JJ (Jeff “Tain” Watts)

Set 2:

- Triple Threat – The Bridge (Edwards)

- Parallel (Joe Harriott)

- Solace (Edwards)

- The Sorcerer (Herbie Hancock)

- Blind Man Stomp (Golding).

The last number was a great New Orleans stomp written by Binker Golding, which the crowd loved – perhaps showing their real preference would have been for something more traditional. Myself, I was happier with what came before. Counting 11 to the bar certainly woke me up PDQ!

UPDATE (2011-02-06): I have now listened to their debut CD. Confirms my view that these guys are not people you’d want to mess with. They have some serious intent and the strong musical skills to achieve it. This is great music.

UPDATE #2 (2011-02-08): The band’s next outing is in a bookshop! First, pre-dawn Saturday morning gigs, then playing in libraries! What next? An appearance on The Archers? Or music to accompany a TV cooking program?

Recent Listening 5: Hungarian Modern Jazz

A quick mention of various Hungarian jazz CDs that I’ve been listening to this week, some of the music cool and some hot. I have heard several of these performers live, and hope to do so again: pianist Szabo Daniel (whose hands are shown above), double bassist Olah Zoltan (playing on both the Toth Viktor and the Budapest Jazz Orchestra CDs), and the superb Trio Midnight.

Szabo Daniel [1998]: At the Moment. Hungary: Magneoton/Germany: Warner Music.

Trio Midnight [1999]: On Track. Featuring Lee Konitz. Budapest, Hungary: Well CD 2000.

Toth Viktor Trio [2000]: Toth Viktor Trio. Budapest, Hungary.

Budapest Jazz Orchestra [2000]: Budapest Jazz Orchestra. Budapest, Hungary. Recorded at Aquarium Studio.

Note: Entries in this series here.

Last Tango in Braidwood

Here is a review of a concert of student compositions, held at the then Canberra School of Music, on 31 October 1978, which I wrote at the time.

It is interesting that the student composer of one of the least impressive works played at that concert should end up as a professional composer (Knehans), while that of the most impressive, it seems, did not (McGuiness). But the style of McGuiness’ piece was closer to what we now call downtown, and I have never been much impressed with uptown contemporary music, despite its hold on the academy and the new music establishment. My sympathies for downtown and antipathy to uptown music has as much to do with the various aspirations of these styles as with how the resulting music sounds.

Ian Davies: Last Tango in Braidwood or I Might be Wrong. Very good – at times impressionistic, at other times expressionistic. Owes a lot to Sculthorpe (before his turn to late romanticism). Good stereo effects. Held together well, except for the ending. The last 15% of the piece would be better deleted and replaced by something much shorter, and more unified with the first 85%.

Alexandra Campbell: Harmonic Music. More harmonic than Davies’ piece, but not at all traditional. The piece seemed to lack any unifying idea, and just seemed a series of random statements, the phrases disconnected and unrelated. A pity, because some of the individual phrases were nice-sounding. Showed clear understanding of instrumental possibilities, especially the winds – perhaps fittingly for a composer who plays the oboe.

Richard Webb: Cube. If the previous piece was incoherent, this was completely incomprehensible. Like listening to someone speaking in an unknown foreign language, not even the individual phrases made sense. The piece was just a cacophony of effects, overloud and overlong.

Richard Webb: Maya. A tape realization, this was also overloud and overlong. Not gebrauchsmusik, but boretheaudiencemusik. Listening to electronic special effects in 1978 brings to mind only Star Wars and science fiction novels, so perhaps these effects can’t be used any longer. The audience began to talk about 3/4 of the way through, so my boredom was not unique.

Andrew McGuiness: Simple Music (for Simple People). This was superb! Fantastic! The ensemble stood in darkness and played according to graphic instructions written on paper affixed to the wall, each page of instructions illuminated by a lady (Alex Campbell) holding a torch, as it was being played. Sitting in the dark with just the torch light, it felt like we were watching a sunrise. And the music mirrored this feeling perfectly, though it was not programmatic or symbolic at all. The music was impressionistic and at times pseudo-Balinese (again, a la Sculthorpe). One discord was sustained throughout, I think on an electric piano or on a synth set to “harpsichord”, perhaps. Simply marvellous.

Peter Butler: Champagne will be Served at Interval. Butler played chimes and electronic piano at front. The e-piano was too loud, especially in comparison with the acoustic piano at rear. Apart from this the piece was very good. The “form” was a call-and-response structure, with the call issued by one of the five sections (strings; e-piano; piano; guitar and flute; and guitar and flute) to another, with the chimes intervening every so often to signal a climax, or perhaps an anti-climax. The calls – were these questions? – occasionally became fierce, with loud crescendos and sustained ranting, usually ending abruptly or halted by a clang of the chimes. Certainly, as the notes said, a snakes-and-ladders piece. Apparently, only the outline was sketched by the composer, with details added by the performers. It would be interesting to see the score. This was the most expressionistic piece of the evening (ignoring the tape realization).

Peter Butler: One Dollar per Glass. A piece for solo guitar, performed by Brian Lewis, this was a collage of special effects: tapping of the base of the guitar; playing it with a cello bow, a beer glass and a spoon; and re-tuning the instrument while it was being played. The second half of the piece was more overboard with effects than the first, which at least required some guitar-playing skills from the performer.

Douglas Knehans: Survey in Regions (A Tragedy in 4 Parts). Structured on Eliot’s poem, Portrait of a Lady, the piece was supported by rude tape noises. Some of these tape recordings were verses of the poem, although others sounded like Ronnie Barker speaking. I was unable not to laugh each time Barker’s voice was heard. The piece seemed sentimental and insincere, because so many cues in the poem were missed or ignored: “attenuated tones of violins, Mingled with remote cornets”, “a dull tom-tom begins”, etc. The only excitement was visual, since the performers each played many instruments (although only ever one at a time), so that everyone was running around: organist to xylophone, and then back; guitarist to bass drum and back, only to be followed to the drum immediately by the lady percussionist. Musically, the piece made no sense to me, although the organ had some nice phrases now and again.

Caravan in Brisbane

While posting about great jazz gigs, I remembered one superb performance I’d forgotten to record. On 27 November 2009, I heard a gypsy-style jazz group play at Brisbane Jazz Club. The Club has a million-dollar location at Kangaroo Point on the Brisbane River, looking back towards the city. Watching performers against a large window showing a darkening city skyscape across the water was just magical. I hope that the club can recover from the recent floods and return to their home.

The audience that night was about 50, including tables of people speaking Japanese and Russian. The band was advertised as Cam Ford’s Gypsy Swingers, but I’m not sure everyone was there. The line-up included Ian Date, leader, on acoustic guitar and trumpet, his brother Nigel Date on acoustic guitar, Daniel Weltlinger on violin, and two players whose names I failed to catch – an acoustic guitarist and an electric bass player. Later in the evening, the five were joined by another acoustic guitarist and a clarinet player (Dan?). The music included some flamenco (to be expected with all those guitars) and was mostly 1920s Hot Club de France-style arrangements. Most pieces had a fast, 4/4 tradjazz beat, with the bass playing a walking bass part. This is a style of jazz I am not fond of, since much of it sounds the same, but the players showed real skill. The violin or the lead guitar usually played a solo over the top, or sometimes, the two – violin and lead guitar – played a call-and-response duet. These tunes were all done with energy, enthusiasm and skill.

With the full line-up of seven, the group played an absolutely superb arrangement of Caravan, a song I have blogged about before. The arrangement began with the violin playing the melody over guitar rhythms and an ostinato bass. This first run through was then followed by several choruses where the melody was played in unison first by the violin and one guitar, and then with a second guitar playing a 2nd or a 3rd higher than the unison part. The effect of this was something like an Hawaiiwan guitar, and created a sound that was iridescent, shimmering like the flickering lights on the river in the window behind the musicians.

To me, the stand-out performer on the night was the violinist, Daniel Weltlinger, whom nothing seemed to faze. At one point, when the two additional players joined, he was shouting chord changes to the clarinetist while improvising his own solo at the same time.

Scottish Marley Chingus

A quick shout-out to Marley Chingus Jazz Explosion, who play at The Caledonia alternate Friday nights, to where a friend invited me last night. In truth, I’ve seen their posters for a couple of years, but had avoided going to hear them. Their twee name makes them sound like a tribute band, and who wants to listen to people with insufficient imagination to play their own music, or even to invent their own name?

But the loss was mine. What a great performance! The quartet comprises Colin Lamont on drums, Dave Spencer on e-double bass, Bob Whittaker on tenor, and long-fingered medic Misha Gray on e-piano. Last night they also had guesting another tenor player, whose name I did not catch. (And Principal Cellist of the RLPO, Jonathan Aasgaard, was also in the crowd.) Mingus, Monk, and Shorter featured (eg, JuJu), as well as their own fine compositions in brazen, hard-driving, funky, modal post-bop – serious early-60s jazz, before the harmonic emptiness of fusion took prominence. What I particularly liked was that their solos did not sound the same from song to song; quite a few jazz performers really play the same solos whatever the underlying tune. Gray’s trills, two-finger glissandos, and left-hand ostinatos were a delight, recalling early piano styles, and I also liked his occasional Shearing-style block chords. He could do more with those, I think.

Pity about the name, though.

Art: Bridget Riley at the National Gallery, London

I saw an exhibition of Bridget Riley’s work in a career retrospective of her work at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art some five years ago. With what great delight her paintings shimmered, danced and cavorted across the canvas before one’s very eyes, while the waters of the sunlit Harbour did the same through the MCA’s windows! I was reminded of this seeing the current, small exhibition of her work in the Sun-Lit Room at the National Gallery, London. While “sunlit” is an aspirational term in London this week, her paintings, some of them painted directly onto the walls themselves, still dance before our eyes. Robert Melville, writing in the New Statesman in 1970, expressed it best: “No painter, dead or alive, has ever made us more aware of our eyes than Bridget Riley.”

Morton Feldman once said of the paintings of the abstract expressionists that they only perform for you as you leave them. “Not long ago Guston asked some friends, myself among them, to see his recent work at a warehouse. The paintings were like sleeping giants, hardly breathing. As the others were leaving, I turned for a last look, then said to him, “There they are. They’re up.” They were already engulfing the room.” (Feldman, p. 100, cited in Bernard, p. 182) Riley’s paintings are up and dancing before you even enter the room! What pleasure these paintings give, what delight one has just being in their company!

References:

I have posted before about the art of the national treasure who is Ms Riley, here.

Reviews of the NG exhibition here: Hilary Spurling, Maev Kennedy, and Adrian Searle. And images from the Exhibition here.

The image above shows two assistants of Bridget Riley painting her work Arcadia 1 directly onto the wall at the National Gallery. Photograph credit: The National Gallery.

Morton Feldman [1965]: Philip Guston: The last painter. Art News Annual 1966 (Winter 1965).

Jonathan W. Bernard [2002]: Feldman’s painters. pp. 173-215, in: Steven Johnson (Editor): The New York Schools of Music and Visual Arts. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

Santayana and chemistry

The philosopher George Santayana (1863-1952), whom I have written about before, was fortunate to have two families, one Spanish and one American. His mother was a widow when she married his father, and his parents later preferred to live in different countries – the USA and Spain, respectively. Santayana spent part of his childhood with each, and accordingly grew up knowing his Bostonian step-family and their cousins, relatives of his mother’s first husband, the American Sturgis family. Among these relatives, his step-cousin Susan Sturgis (1846-1923) is mentioned briefly in Santayana’s 1944 autobiography (page 80). (See Footnote #1 below.)

Susan Sturgis was married twice, the second time in 1876 to Henry Bigelow Williams (1844-1912), a widower and property developer. In 1890, Williams commissioned a stained glass window from Louis Tiffany for the All Souls Unitarian Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts (pictured below), to commemorate his first wife, Sarah Louisa Frothingham (1851-1871).

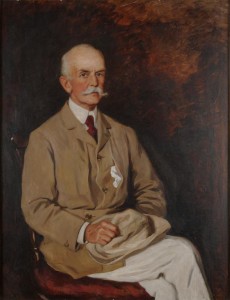

The first marriage of Susan Sturgis was in 1867, to Henry Horton McBurney (1843-1875). McBurney’s younger brother, Charles Heber McBurney (1845-1913) went on to fame as a surgeon, developer of the procedure for diagnosis of appendicitis and removal of the appendix. The normal place of incision for an appendectomy is known to every medical student still as McBurney’s Point. The portrait below of Charles Heber McBurney was painted in 1911 by Ellen Emmet Rand (1875-1941), and is still in the possession of the McBurney family. (The painting is copyright Gerard McBurney 2013. As Ellen Emmet married William Blanchard Rand in 1911, this is possibly the first painting she signed with her married name.)

Charles H. McBurney was also a member of the medical team which treated US President William McKinley following his assassination. He and his wife, Margaret Willoughby Weston (1846-1909), had two sons, Henry and Malcolm, and a daughter, Alice. The younger son, Malcolm, also became a doctor and married, having a daughter, but he died young. Alice McBurney married Austen Fox Riggs (1876-1940), a protege of her father, Charles, and a pioneer of psychiatry. He founded what is now the Austen Riggs Centre in Stockbridge, MA, in 1907. They had two children, one of whom, Benjamin Riggs (c.1914-1992), was also a distinguished psychiatrist, as well as a musician, sailor, and boat builder.

The elder son of Charles and Margaret, Henry McBurney (1874-1956), was an engineer whose own son, Charles Brian Montagu McBurney (1914-1979), became a famous Cambridge University archaeologist. CBM’s children are the composer Gerard McBurney, the actor/director Simon McBurney OBE, and the art-historian, Henrietta Ryan FLS, FSA. CBM’s sister, Daphne (1912-1997), married Richard Farmer. Their four children were Angela Farmer, a yoga specialist, David Farmer FRS, a distinguished oceanographer, whose daughter Delphine Farmer, is a chemist, Michael Farmer, painting conservator, and Henry Farmer, an IT specialist, whose son, Olivier Farmer, is a psychiatrist.

Henry H. and Charles H. had three sisters, Jane McBurney (born 1835 or 1836), Mary McBurney (1839- ), Almeria McBurney (who died young), and another brother, John Wayland McBurney (1848-1885). They were born in Roxbury, MA, to Charles McBurney and Rosina Horton; Charles senior (1803 Ireland – Boston 1880) was initially a saddler and harness maker in Tremont Row, Boston – the image above shows a label from a trunk he made. Later, he was a pioneer of the rubber industry, for example, receiving a patent in 1858 for elastic pipe, and was a partner in the Boston Belting Company. It is perhaps not a coincidence that Charles junior pioneered the use of rubber gloves by medical staff during surgery.

All three boys graduated from Harvard (Henry in 1862, Charles in 1866, and John in 1869). John married Louisa Eldridge in 1878, and they had a daughter, May (or Mary) Ruth McBurney (1879-1947). May married William Howard Gardiner Jr. (1875-1952) in 1918, and on her death left an endowment to Harvard University to establish the Gardiner Professor in Oceanic History and Affairs to honour her husband. John worked for his father’s company and later in his own brokerage firm, Barnes, McBurney & Co; he died of tuberculosis.

Mary (or Mamie) McBurney married Dr Barthold Schlesinger (1828-1905), who was born in Germany of a Jewish ethnic background, and immigrated to the USA possibly in 1840, becoming a citizen in 1858. For many years, from at least 1855, he was a director of a steel company, Naylor and Co, the US subsidiary of leading steel firm Naylor Vickers, of Sheffield, UK. Barthold’s brother, Sebastian Benson Schlesinger (1837-1917), was also a director of Naylor & Co from 1855 to at least 1885; he was also a composer, mostly it seems of lieder and piano music; some of his music has been performed at the London Proms. At the time, Naylor Vickers were renowned for their manufacture of church bells, but in the 20th century, under the name of Vickers, they became a leading British aerospace and defence engineering firm; the last independent part of Vickers was bought by Rolls-Royce in 1999.

Mary and Barthold Schlesinger appear to have had at least five children, Mary (1859- , married in 1894 to Arthur Perrin, 1857- ), Barthold (1873- ), Helen (1874- , married in 1901 to James Alfred Parker, 1869- ), Leonora (1878- , married in 1902 to James Lovell Little, c. 1875- ), and Marion (1880- , married in 1905 to Jasper Whiting, 1868- ). The Schlesingers owned an estate of 28 acres at Brookline, Boston, called Southwood. In 1879, they commissioned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead (1822-1903), the designer of Central Park in New York and Prospect Park in Brooklyn, to design the gardens of Southwood; some 19 acres of this estate now comprises the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, of the Greek Orthodox Church of North America. The Schlesingers were lovers of art and music, and kept a house in Paris for many years. An 1873 portrait of Barthold Schlesinger by William Morris Hunt (1824-1879) hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

While a student at Harvard, Henry H. McBurney was a prominent rower. After graduation, he spent 2 years in Europe, working in the laboratories of two of the 19th century’s greatest chemists: Adolphe Wurtz in Paris and Robert Bunsen in Heidelberg. Presumably, even Harvard graduates did not get to spend time working with famous chemists without at least strong letters of recommendation from their professors, so Henry McBurney must have been better than average as a chemistry student. He returned to Massachusetts to work in the then company, Boston Elastic Fabric Company, of his father, and then, from November 1866, as partner for another firm, Campbell, Whittier, and Co. From what I can discover, this company was a leading engineering firm, building in 1866 the world’s first cog locomotive, for example, and, from 1867, manufacturing and selling an early commercial elevator.

Henry H. and Susan S. McBurney had three children: Mary McBurney (1867- , in 1889 married Frederick Parker), Thomas Curtis McBurney (1870-1874), and Margaret McBurney (1873-, in 1892 married Henry Remsen Whitehouse). Mary McBurney and Frederick Parker had five children: Frederic Parker (1890-), Elizabeth Parker (1891-), Henry McBurney Parker (1893-), Thomas Parker (1898.04.20-1898.08.30), and Mary Parker (1899-). Margaret McBurney and Henry Whitehouse had a daughter, Beatrix Whitehouse (1893-). The name “Thomas” seems to have been ill-fated in this extended family.

HH died suddenly in Bournemouth, England, in 1875, after suffering from a lung disease. As with any early death, I wonder what he could have achieved in life had he lived longer.

POSTSCRIPT (Added 2011-11-21): Henry H. McBurney’s visit to the Heidelberg chemistry lab of Robert Bunsen is mentioned in an account published in 1899 by American chemist, Henry Carrington Bolton, who also worked with Bunsen, and indeed with Wurtz. Bolton refers to McBurney as “Harry McBurney, of Boston” (p. 869).

POSTSCRIPT 2 (Added 2012-10-09): According to the 1912 Harvard Class Report for the Class of 1862 (see Ware 1912), Henry H. McBurney spent the year from September 1862 in Paris with Wurtz and the following year in Heidelberg with Bunsen. He therefore presumably just missed meeting Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1841-1880), son of composer Felix, who graduated in chemistry from Heidelberg in 1863. PM-B went on to co-found the chemicals firm Agfa, an acronym for Aktien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation. I wonder if Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy ever returned to visit Bunsen in the year that Henry McBurney was there.

POSTSCRIPT 3 (Added 2013-01-20): I am most grateful to Gerard McBurney for the portrait of Charles H. McBurney, and for additional information on the family. I am also grateful to Henrietta McBurney Ryan for information. All mistakes and omissions, however, are my own.

NOTE: If you know more about any of the people mentioned in this post or their families, I would welcome hearing from you. Email: peter [at] vukutu.com

References:

Henry Carrington Bolton [1899]: Reminiscences of Bunsen and the Heidelberg Laboratory, 1863-1865. Science, New Series Volume X (259): 865-870. 15 December 1899. Available here.

George Santayana [1944]: Persons and Places: The Background of My Life. (London, UK: Constable.) (New York, USA: Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

Charles Pickard Ware (Editor) [1912]: 1862 – Class Report – 1912. Class of Sixty-Two. Harvard University. Fiftieth Anniversary. Cambridge, MA, USA, Available here.

Footnotes:

1. Santayana writes as follows about Susan Sturgis Williams (Santayana 1944, page 74 in the US edition):

Nothing withered, however, about their sister Susie, one of the five Susie Sturgises of that epoch, all handsome women, but none more agreeably handsome than this one, called Susie Mac-Burney and Susie Williams successively after her two husbands. When I knew her best she was a woman between fifty and sixty, stout, placid, intelligent, without an affectation or a prejudice, adding a grain of malice to the Sturgis affability, without meaning or doing the least unkindness. I felt that she had something of the Spanish feeling, So Catholic or so Moorish, that nothing in this world is of terrible importance. Everything happens, and we had better take it all as easily or as resignedly as possible. But this without a shadow of religion. Morally, therefore, she may not have been complete; but physically and socially she was completeness itself, and friendliness and understanding. She was not awed by Boston. Her first marriage was disapproved, her husband being an outsider and considered unreliable; but she weathered whatever domestic storms may have ensued, and didn’t mind. Her second husband was like her father, a man with a checkered business career; but he too survived all storms, and seemed the healthier and happier for them. They appeared to be well enough off. In her motherliness there was something queenly, she moved well, she spoke well, and her freedom from prejudice never descended to vulgarity or loss of dignity. Her mother’s modest solid nature had excluded in her the worst of her father’s foibles, while the Sturgis warmth and amiability had been added to make her a charming woman.”

POST MOST RECENTLY UPDATED: 2013-03-26.

Chance would be a fine thing

Music critic Alex Ross discusses John Cage’s music in a recent article in The New Yorker. Ross goes some way before he trips up, using those dreaded – and completely inappropriate – words “randomness” and “chance”:

Later in the forties, he [Cage] laid out “gamuts” – gridlike arrays of preset sounds – trying to go from one to the next without consciously shaping the outcome. He read widely in South Asian and East Asian thought, his readings guided by the young Indian musician Gita Sarabhai and, later, by the Zen scholar Daisetz Suzuki. Sarabhai supplied him with a pivotal formulation of music’s purpose: “to sober and quiet the mind, thus rendering it susceptible to divine influences.” Cage also looked to Meister Eckhart and Thomas Aquinas, finding another motto in Aquinas’s declaration that “art imitates nature in the manner of its operation.”

. . .

In 1951, writing the closing movement of his Concerto for Prepared Piano, he finally let nature run its course, flipping coins and consulting the I Ching to determine which elements of his charts should come next. “Music of Changes,” a forty-three-minute piece of solo piano, was written entirely in this manner, the labor-intensive process consuming most of a year.

As randomness took over, so did noise. “Imaginary Landscape No. 4″ employs twelve radios, whose tuning, [page-break] volume, and tone are governed by chance operations.” [pages 57-58]

That even such a sympathetic, literate, and erudite observer as Alex Ross should misconstrue what Cage was doing with the I Ching as based on chance events is disappointing. But, as I’ve argued before about Cage’s music, the belief that the material world is all there is is so deeply entrenched in contemporary western culture that westerners seem rarely able to conceive of other ways of being. Tossing coins may seem to be a chance operation to someone unversed in eastern philosophy, but was surely not to John Cage.

References:

Alex Ross [2010]: Searching for silence. John Cage’s art of noise. The New Yorker, 4 October 2010, pp. 52-61.

James Pritchett [1993]: The Music of John Cage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Here are other posts on music and art.