I am belatedly posting about a superb homily I heard given at a mass to celebrate the Fourth Centenary of the (then) English Province of the Society of Jesus, held in Farm Street Church, London on 21 January 2023. The mass was celebrated by Vincent Cardinal Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster, and the sermon given by Fr Damian Howard SJ, Provincial of the British Province. The music at the mass included the world premiere of James MacMillan’s “Precious in the sight of the Lord” (with MacMillan in the congregation).

Archive for the ‘Oratory’ Category

Page 0 of 2

Loud Living in Cambridge

I was most fortunate this week to hear Jan Lisiecki in an outstanding recital at the West Road Concert Hall, Department of Music, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, on 26 February 2024, in a concert sponsored by Camerata Musica Cambridge. West Road Hall is a fine modern hall with very nice acoustics, and was fully packed. The hall management turned off the lights over the audience (as in a theatre), which should happen more often. Perhaps that darkness helped create the atmosphere of great seriousness this performance had. I later learnt that this recital was the twelfth time in the series that Mr Lisiecki had played the Preludes program.

Oratory at Nudgee

This is a short post to record for history a very fine speech by Mr Oscar Roati, School Captain of St Joseph’s Nudgee College, Brisbane, Australia, at the Investiture Ceremony for the 2024 Senior Class on 24 January 2024. Apparently, his father Alex Roati was a Vice-Captain and his two brothers were both Captains of Nudgee. The speech can be seen here, from minute 41:20.

The personality of Robert Mugabe

I have remarked before that Robert Mugabe was one of the best orators I have ever heard. I am not alone in having been impressed. Below is an assessment of Mugabe’s oratory and personality, by Zimbabwean journalist Jan Raath, published in The Times (London), 12 November 2017, under the headline, “Forty years ago, I too was beguiled by Robert Mugabe, the young guerrilla leader”.

I will treasure the events of yesterday afternoon for the rest of my life. I had driven to the Harare international conference centre to hear a rather dry debate on the impeachment of Robert Mugabe, the man I have been covering for this newspaper since 1975.

Continue reading ‘The personality of Robert Mugabe’

Piping 101

Leslie Claret (Kurtwood Smith) in Patriot (S1, Ep2, min 17):

Sell them on the structure. You can talk about it with confidence. Keep it simple. A little something like this, John.

Hey. Let me walk you through the Donnelly nut spacing and crack system rim-riding rip configuration. Using a field of half-C sprats, and brass-fitted nickel slits, our bracketed caps, and splay-flexed brace columns, vent dampers to dampening hatch depths of one half meter from the damper crown to the spur of plinth. How? Well, we bolster twelve husked nuts to each girdle-jerry, while flex tandems press a task apparatus of ten vertically-composited patch-hamplers. Then, pinflam-fastened pan traps at both maiden-apexes of the jim-joist.

A little something like that, Lakeman.

Praise to the writers of this series! The sounds here reminded me of the second stanza of Browning’s The Pied Piper of Hamelin:

Hamelin Town’s in Brunswick,

By famous Hanover city;

The river Weser, deep and wide,

Washes its wall on the southern side;

A pleasanter spot you never spied;

But, when begins my ditty,

Almost five hundred years ago,

To see the townsfolk suffer so

From vermin, was a pity.Rats!

They fought the dogs and killed the cats,

And bit the babies in the cradles,

And ate the cheeses out of the vats,

And licked the soup from the cooks’ own ladles,

Split open the kegs of salted sprats,

Made nests inside men’s Sunday hats,

And even spoiled the women’s chats,

By drowning their speaking

With shrieking and squeaking

In fifty different sharps and flats.

John Curtin Memorial Lecture Series at ANU

For some years starting in 1970, the Australian National University in Canberra hosted a public lecture series named for war-time Labor Prime Minister, John Curtin. As the list of eminent speakers below indicates, this lecture series honoured Curtin and the labour movement.

In 1979, the chosen speaker was the prominent right-wing journalist, Alan Reid. Although he had known Curtin and Curtin’s successor as PM, Ben Chifley, Reid had worked as a journalist in the Packer stable, had played a part in the Labor split in the 1950s, had privately advised Menzies and Holt, and had deplored the Whitlam government. Even Liberal PM John Gorton thought Reid despicable, famously saying once that while he, Gorton, had been born a bastard, Reid had become one through his own efforts. Reid was an entirely inappropriate person to give a lecture in a series honouring Curtin.

Continue reading ‘John Curtin Memorial Lecture Series at ANU’

London life

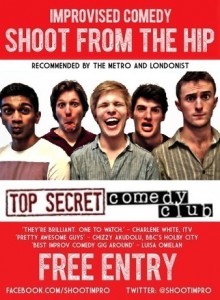

Shoot from the Hip’s Improv Jams and Workshops, London (HT: WP).

London life

Speakers’ Corner, Hyde Park, London.

Oral and written cultures at FBI and CIA

Henry Crumpton’s fascinating book about his time working for CIA includes an account of his time in 1998 and 1999 seconded, as a CIA liaison, to a senior post in the FBI. This account has a profound reflection of the cultural differences between the two organizations, differences which arise from their different primary missions: for FBI, the mission is to solve criminal cases (which is essentially a backwards-looking activity played against a suspect’s lawyers) versus, for CIA, the identification and avoidance of potential threats (which is inherently forwards-looking and played for an intelligence client). Crumpton summarized his reflections (contained on pages 112-115 of his book) in a Politico op-ed column here:

First, the FBI valued oral communications as much as or more than written. The FBI’s special-agent culture emphasized investigations and arrests over writing and analysis. It harbored a reluctance to write anything that could be deemed discoverable by any future defense counsel. It maintained investigative flexibility and less risk if its findings were not written — or at least not formally drafted into a data system. Its agents were not selected or trained to write.

This is also tied to rank and status: Clerks and analysts write, not agents. Agents saw writing as a petty chore, best left to others.

In contrast, most CIA operations officers had to write copiously and quickly. To have the president or other senior policymakers benefit from clandestine written reports — that was the holy grail. CIA officers prized clear, high-impact written content.

The second major difference between the FBI and CIA was their information systems. The FBI did not have one — at least one that functioned. An FBI analyst could not understand a field office’s investigation without going to that office and working with its agents for days or even weeks. With minimal reporting, there was no other choice.

CIA stations, in contrast, write reports on just about everything — because without written reports, there was no intelligence for analysts and other customers to assess. The CIA required high-speed information systems with massive data management, and upgraded systems constantly.The third difference was size. The FBI was enormous compared with the CIA. The FBI personnel deployed to investigate the East Africa bombings, for example, outnumbered all CIA operations officers on the entire African continent. The FBI’s New York field office had more agents than the CIA had operations officers around the world. The FBI routinely dispatched at least two agents for almost any task. CIA officers usually operated alone — certainly in the development, recruitment and handling of sources.

A fourth difference was the importance of sources. While both the FBI and the CIA placed a premium on a good source, the FBI did not actively pursue them beyond the context of an investigation. The agents would follow leads and seek a cooperative witness or a snitch, often compelled to cooperate or face legal consequences.

FBI agents seldom discussed sources. When they did, it was often in derogatory fashion. But they discussed suspects endlessly. That was their pursuit. And for the FBI, sometimes sources and suspects were one and the same.

CIA officers, on the other hand, routinely compared notes and lessons learned about developing, recruiting and handling sources — though couched so that specifics were not revealed. Ops officers’ missions and their sense of accomplishment, even their professional identity, depended on the success of sources and the intelligence they produced. FBI agents wanted evidence and testimony from witnesses that led to convictions and press conferences.

A fifth difference was money. The FBI had severe limitations on how much agents could spend and how they could spend it. The process to authorize the payment of an informant or just to travel was laborious.

As a CIA officer, however, I routinely carried several thousand dollars in cash — to entertain prospective recruitment targets, compensate sources, buy equipment or bribe foreign officials to get things done. I usually had to replenish my well-used revolving fund every month.

When I told FBI agents this, they seemed doubtful that such behavior was even legal. I often had to explain that the CIA did not break U.S. laws — just foreign laws.

Sixth, the FBI harbored a sense that because it worked under the Justice Department, it had more legal authority than the CIA. Some, after a few drinks, expressed moral objections to the CIA’s covert actions. I would argue that covert action, directed by the president and approved by congressional oversight committees, is legal. But somehow the notion of breaking foreign laws seemed less than ideal to some of my FBI partners.

Seventh, the FBI loved the press and worked hard to curry favor with it. For the CIA’s Clandestine Service, the media was taboo. Most of us had experienced occasions when media leaks undermined operations. Sometimes, our sources died because of this coverage. On top of that, we felt that the media seemed intent on portraying the CIA in a negative light. A CIA operations officer avoided the press like the plague.For the FBI, it was the opposite. Positive press could help fight crime and boost prestige and resources. Every FBI field office worked the media.

Eighth, the FBI collected evidence for its own use, to prosecute a criminal. The CIA primarily collected intelligence for others, whether a policymaker, war fighter or diplomat. The FBI, therefore, lacked a culture of customer service beyond the Justice Department. Without a customer for intelligence, the CIA had no mission.

Ninth, the FBI’s field offices, especially New York, acted as their own centers of authority, even holding evidence, because of their link to the local prosecutor. A city district attorney and civic political actors had great influence over an investigation.

The CIA station instead had to report intelligence to Langley, because the incentive came from there and beyond — particularly the White House.

Tenth, the FBI worked Congress. Every FBI field office had representatives dedicated to supporting congressional delegates. The FBI also had the authority to investigate members of Congress for illegal activity. So the bureau had both carrots and sticks.

But the CIA, particularly the Clandestine Service, had minimal leverage with Congress. Most CIA officers engaged Congress only when required to testify.”

The consequences of these differences for us all are immense. Crumpton again:

The FBI is still measuring success, according to one well-informed confidant, based on arrests and criminal convictions — not on the value of intelligence collected and disseminated to its customers.

When I served as U.S. coordinator for counterterrorism, from 2005 to 2007, I was a voracious consumer of intelligence. Yet I never saw an FBI intelligence report that helped inform U.S. counterterrorism policy. Has there been any improvement?”

Reference:

Henry A Crumpton [2012]: The Art of Intelligence: Lessons from a Life in the CIA’s Clandestine Service. (New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books).

Political talk

James Button, one-time speech-writer to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, wrote this in his recent book:

When Rudd spoke at the Department’s Christmas party, he had sketched a triangle in the air that distilled the work of producing a policy or speech into a three-point plan: where are we now; where do we want to go and why; how are we going to get there? The second point – where do we want to go and why – expressed our values, Rudd said. It was a simple way to structure a speech and I often used it when writing speeches in the year to come.” (Button 2012, page 55, large print edition).

Reading this I was reminded how inadequate I had found the analysis of political speech propounded by anthropologist Michael Silverstein in his short book on political talk (Silverstein 2003). He seems to view political speech as mere information transfer, and the utterances made therefore as essentially being propositions – statements about the world that are either true or false. Perhaps these propositions may be covered in rhetorical glitter, or presented incrementally, or subtly, or cleverly, but propositions they remain. I know of no politician, and I can think of none, who speaks that way. All political speeches (at least in the languages known to me) are calls to action of one form or another. These actions may be undertaken by the speaker or their political party – “If elected, I will do XYZ” – or they may be actions which the current elected officials should be doing – “Our Government should be doing XYZ.” Implicit in such calls is always another call, to an action by the listener: “Vote for me”. Even lists of past achievements, which Button mentions Rudd was fond of giving, are implicit or explicit entreaties for votes.

Of course, such calls to action may, of necessity, be supported by elaborate propositional statements about the world as it is, or as it could be or should be, as Rudd’s structure shows. And such propositions may be believed or not, by listeners. But people called to action do not evaluate the calls they hear the way they would propositions. It makes no sense, for instance, to talk about the “truth” or “falsity” of an action, or even of a call to action. Instead, we assess such calls on the basis of the sincerity or commitment of the speaker, on the appropriateness or feasibility or ease or legality of the action, on the consequences of the proposed action, on its costs and benefits, its likelihood of success, its potential side effects, on how it compares to any alternative actions, on the extent to which others will support it also, etc.

What has always struck me about Barack Obama’s speeches, particularly those during his first run for President in 2007-2008, is how often he makes calls-to-action for actions to be undertaken by his listeners: He would say “We should do X”, but actually mean, “You-all should do X”, since the action is often not something he can do alone, or even at all. “Yes we can!” was of this form, since he is saying, “Yes, we can take back the government from the Republicans, by us all voting.” From past political speeches I have read or seen, it seems to me that only JFK, MLK and RFK regularly spoke in this way, although I am sure there must have been other politicians who did. This approach and the associated language comes directly from Obama’s work as a community organizer: success in that role consists in persuading people to work together on their own joint behalf. Having spent lots of time in the company of foreign aid workers in Africa, this voice and these idioms were very familiar to me when I first heard Obama speak.

Rudd’s three-part structure matches closely to the formalism proposed by Atkinson et al. [2005] for making proposals for action in multi-party dialogs over action, a structure that supports rational critique and assessment of the proposed action, along the dimensions mentioned above.

References:

K. Atkinson, T. Bench-Capon and P. McBurney [2005]: A dialogue-game protocol for multi-agent argument over proposals for action. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, 11 (2): 153-171.

James Button [2012]: Speechless: A Year in my Father’s Business. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

Michael Silverstein [2003]: Talking Politics: The Substance of Style from Abe to “W”. Chicago, IL, USA: Prickly Paradigm Press.