Last month, I posted some statements by John Berger on drawing. Some of these statements are profound:

A drawing of a tree shows, not a tree, but a tree-being-looked-at. . . . Within the instant of the sight of a tree is established a life-experience.” (page 71)

Berger asserts that we do not draw the objects our eyes seem to look at. Rather, we draw some representation, processed through our mind and through our drawing arm and hand, of that which our minds have seen. And that which our mind has seen is itself a representation (created by mental processing that includes processing by our visual processing apparatus) of what our eyes have seen. Neurologist Oliver Sacks, writing about a blind man who had his sight restored and was unable to understand what he saw, has written movingly about the sophisticated visual processing skills involved in even the simplest acts of seeing, skills which most of us learn as young children (Sacks 1993).

So a drawing of a tree is certainly not itself a tree, and not even a direct, two-dimensional representation of a tree, but a two-dimensional hand-processed manifestation of a visually-processed mental manifestation of a tree. Indeed, perhaps not even always this, as Marion Milner has reminded us: A drawing of a tree is in fact a two-dimensional representation of the process of manifesting through hand-drawing a mental representation of a tree. Is it any wonder, then, that painted trees may look as distinctive and awe-inspiring as those of Caspar David Friedrich (shown above) or Katie Allen?

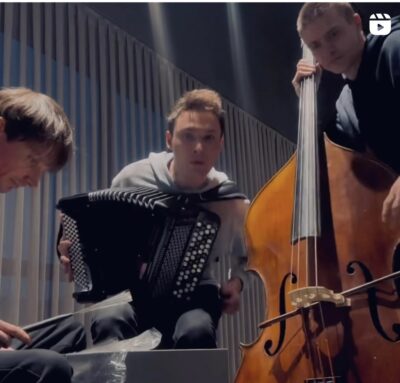

As it happens, we still know very little, scientifically, about the internal mental representations that our minds have of our bodies. Recent research, by Matthew Longo and Patrick Hazzard, suggests that, on average, our mental representations of our own hands are inaccurate. It would be interesting to see if the same distortions are true of people whose work or avocation requires them to finely-control their hand movements: for example, jewellers, string players, pianists, guitarists, surgeons, snooker-players. Do virtuoso trumpeters, capable of double-, triple- or even quadruple-tonguing, have sophisticated mental representations of their tongues? Do crippled artists who learn to paint holding a brush with their toes or in their mouth acquire sophisticated and more-accurate mental representations of these organs, too? I would expect so.

These thoughts come to mind as I try to imitate the sound of a baroque violin bow by holding a modern bow higher up the bow. By thus changing the position of my hand, my playing changes dramatically, along with my sense of control or power over the bow, as well as the sounds it produces.

Related posts here, here and here.

References:

John Berger [2005]: Berger on Drawing. Edited by Jim Savage. Aghabullogue, Co. Cork, Eire: Occasional Press. Second Edition, 2007.

Matthew Longo and Patrick Haggard [2010]: An implicit body representation underlying human position sense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107: 11727-11732. Available here.

Marion Milner (Joanna Field) [1950]: On Not Being Able to Paint. London, UK: William Heinemann. Second edition, 1957.

Oliver Sacks[1993]: To see and not see. The New Yorker, 10 May 1993.