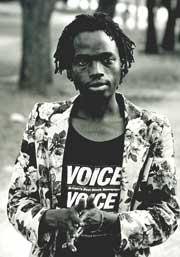

You did not have to visit many bars or nightclubs in downtown Harare in the early 1980s before encountering the late Dambudzo Marechera (1952-1987), Zimbabwean novelist and poet. I knew him slightly, as did anyone who was willing to share a drink with him and enjoy (or endure) a stimulating late-night argument on politics or literature. Some of his writing, for all its coarse language, is powerful and sublime (in the tradition of Burroughs and Genet). David Caute, in a book I have just read, argues correctly that he was a great writer.

The book also captures his personality well, even if it gives the impression that Caute thinks the work forgives the man. It does not. As a person, Marechera was a victim of his addictions and perhaps also of a psychosis – mercurial, abusive, racist, foul-mouthed, illogical, self-destructive, and paranoid: not someone who was nice to be around for very long. Nothing forgives such poor behaviour, not even great writing.

As always when I read David Caute, I am reminded of Graham Greene: both are writers who grapple with the major moral questions and issues of our time, yet both write in the sloppiest of language, insincere and vague, and have the tinnest of ears. Woolly writing might be evidence of woolly thinking or evidence of malice aforethought (perhaps attempting to hide or obfuscate something, as Orwell argued); it could also be evidence of insufficient thinking. In any case, Greene’s and Caute’s arguments are often undone and undermined by their style. We only get as far as page 6 of Caute’s book on Marechera, for example, before we stumble over:

Piled high at the central counter of the Book Fair are copies of his [Marechera’s] new book, Mindblast, published by College Press of Harare, an orange coloured paperback with a surrealist design involving a humanized cat and a black in a space helmet.”

A black what, Dr Caute? A black what? I guess you mean a black person. Just two sentences later, though, you speak of, “An effusive white executive of College Press . . .” So, let me get this right – white people are important enough to have nouns to denote them, but black people not, eh? Hmmm.

Although the effect is racist, I am sure Caute is not deliberately being racist in his use of language here, but rather just sloppy. But the sloppy expression, here as elsewhere, leads one to doubt his sincerity and/or his ear. Of course, someone who spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians could easily forget how offensive the first usage sounds (and is); and we know from Caute’s earlier books that he spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians.

Pressing on, on page 43 we read:

Such rhetoric counts for little against the current surplus of maize, tobacco and beef which only the commercial farmers can guarantee.”

Well, actually, no, Dr Caute. Tobacco and beef were in surplus at the time referred to (1984) due to commercial (ie, mainly white-owned) farms. But maize was in surplus because the avowedly Marxist government of Robert Mugabe used the price mechanism when it came to power to encourage communal farmers (ie, subsistence black farmers) to produce and sell surplus maize crops. This was something so very remarkable – the country in food surplus for its staple food almost immediately after 13 years of civil war and 90 years of insurrection, and because of the fast responsiveness of peasant farmers – that all the papers were full of it. Surely Caute must have heard. (See Herbst 1990 for an account.)

And even beef production was boosted by contributions from communal farmers, particularly after the Government decided not to prosecute the many illegal butcheries competing against the state-owned meat-processing monopoly, the Cold Storage Commission. (One may wonder why a socialist government would not support its own state enterprise against privately-owned competitors until one learns that many members of the Cabinet had financial stakes in the competing butcheries.)

Is the sloppiness in Caute’s sentence then due to Orwellian sleight-of-hand – seeking to promote a case that was factually incorrect – or just due to insufficiently-careful thought? I suspect the latter, although it is throwaway lines like this – as it happens, lines so common in the conversation of white Rhodesians in the 1980s – that make me ponder the sincerity of Caute’s writing.

And, finally, Caute seems eager to berate the left and liberals for their failure to call attention to Robert Mugabe’s ethnic cleansing in Matebeleland in 1982-84, the Gukurahundi campaign. Certainly more could have been said and done, especially publicly, to oppose this. But why is only one side of politics to blame? Both the US and the UK had conservative administrations at the time, both of which (particularly Thatcher’s) made strong representations to Mugabe over the fate of several white Zimbabwe Air Force officers detained and tortured in 1982. These governments did not make nearly such strong representations over the fate of the victims of the Gukurahundi. Perhaps Mugabe was right to accuse the west of racism on this.

And Mugabe’s military campaign in Matabeleland was not launched for no reason: As Caute must know, South Africa and its white Rhodesian friends were engaged in a campaign of terrorist violence against Zimbabwe from its inception, with terrorist bombings throughout the 1980s. The Independence Arch he describes traveling under on the way to Harare Airport was in fact the second arch built to commemorate Independence: the first had been blown up shortly after it was built. And even Joshua Nkomo admitted (at a press conference following his dismissal from Cabinet in February 1982) that he had asked South Africa for assistance to stage a coup after Independence. While Mugabe’s 5th Brigade was certainly engaged in brutal and genocidal murder and rape, the campaign was not against an imaginary enemy.

Although evil may triumph when good people do nothing, from the fact of the triumph of evil it is invalid to infer that nothing was done to oppose it by good people. Where are the mentions in Caute’s account of the strong, high-level and repeated Catholic opposition (both clerical and lay) to Mugabe’s campaign? Where is the mention, in the statement that Mugabe detained people using renewals of Smith’s emergency powers regulations, of the independent review panel established by ZANU(PF) stalwart Herbert Ushewokunze when Minister for Home Affairs, the Detention Review Tribunal, to consider the cases of people detained without trial? The members of this panel included independent lawyers, some of whom were white and liberal. Some people, even some of the people Caute seems to excoriate, were doing their best to stop or ameliorate the evil at the time.

References:

David Caute [1986/2009]: Marechera and the Colonel: A Zimbabwean Writer and the Claims of the State. London, UK: Totterdown Books. Revised edition, 2009.

Jeffrey Herbst [1990]: State Politics in Zimbabwe. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press. Perspectives on Southern Africa Series, Volume 45.