Previously, I’ve mentioned jazz pianist, teacher and composer Hall Overton, here and here. I’ve just come across non-released recordings of free-jazz workshops organized and conducted by pioneer classical composer Edgar Varese in New York in 1957, in which Overton plays piano (and a guy named Mingus plays bass). Varese’s influence continues: a few years ago a concert of some of his music along with contemporary and club-based electronica completely pre-sold-out the 2380-seat capacity of Liverpool’s Royal Philharmonic Hall.

Archive for the ‘Jazz’ Category

Page 3 of 3

Recent listening 4: Caravan

One of life’s pleasures is listening to John Schaefer’s superb radio program on WNYC, New Sounds from New York. I have just heard his recent program presenting different versions of the jazz standard, Caravan. The song is associated with Duke Ellington, although it was composed by trombonist Juan Tizol (pictured playing a valve trombone), and the words were by Irving Mills. Some of these versions I knew and like, particularly the ambient versions of trumpeter John Hassell (minutes 7:17 and 43:38 of the album):

- Jon Hassell: Fascinoma. Water Lily Acoustics, 1999.

The program also included a superb ska version which I did not know before, by the band Hepcat, here.

- Hepcat: Out of Nowhere. Hellcat, 2004. (Reissue of Moon Ska Records, 1983).

One great version not on the program is an arrangement by Gordon Jenkins. This has an agitated string accompaniment, a walking treble sounding like bees circling the soloist, and was included in Season 1 of Mad Men. Someone has posted a recording on Youtube here.

- Mad Men: Music from the Series, volume 1. Lionsgate, 2008.

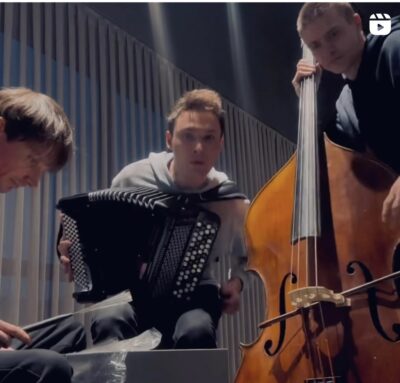

A superb live version I once heard by a violin-and-guitar band in Brisbane I have written about here. Two other great ambient albums are: Posts in this series are here. Postscript (2024-03-12): An exciting live performance of Caravan led by blind pianist Oleg Akkuratov at the 2021 Summer Evenings in Yelabuga Festival in Tatarstan is here. (Hat Tip: AD, who was there.) Postscript (2024-04-18): Another exceptionally good and sublime version is by button accordianist Aydar Salakhov, double bassist Dima Tarbeev, and percussionist Dmitry Mezhenin, on Instagram here. Postscript (2024-05-28):And here is an encore I heard live by pianist (and bongos player) Frank Dupree with members of the Philharmonia Orchestra in the Royal Festival Hall in London on Thursday 7 March 2024.

Vale: Mike Zwerin

This is a belated farewell to Mike Zwerin (1930-2010), jazz trombonist and jazz correspondent for the International Herald Tribune. An American in Paris, he was open in his musical tastes and usually generous in his criticisms; his IHT writings personally sustained many a long journey across far meridians, and helped reinforce the urbane, cosmopolitan, expatriate feel that the IHT had last century (now sadly lost, since the NYT bought out the Washington Post and brought it home to Manhattan). Obits: London Times and The Guardian.

Celebrating Hall Overton

Some months ago, I blogged about Jack Reilly’s account of learning jazz piano and composition from Hall Overton (1920-1972) in 1950s New York, here. I’ve just learnt that The New York Public Library is hosting a special discussion on Overton’s life and career, tomorrow 14 April 2010 at 18:00.

Learning jazz improvisation

A few days ago, writing about bank bonuses, I talked about the skills needed to get-things-done, a form of intelligence I believe is distinct (and rarer than) other, better-known forms — mathematical, linguistic, emotional, etc. There are in fact many skill sets and forms of intelligence which don’t feature prominently in our text-biased culture. One of these is musical intelligence, and I have come across a fascinating description of taking jazz improvisation and composition lessons from pianist and composer Hall Overton (1920-1972), written by Jack Reilly (1932-2018):

The cigarette dangled out the right side of his mouth, the smoke rising causing his left eye to squint, the ashes from the burning bush got longer and longer, poised precipitously to fall at any moment on the keyboard. Hall always sat at the upright piano smoking, all the while playing, correcting, and making comments on my new assighment, exercises in two-part modern counterpoint. I was perched on a rickety chair to his left, listening intensely to his brilliant exegesis, waiting in vain for the inch-long+ cigarette ash to fall. The ashes never fell! Hall instinctively knew the precise moment to stop playing , take the butt out of his mouth and flick the ashes in the tray on the upright piano to his left. He would then throw the butt in the ash tray and immediately light another cigarette. His concentration and attention to every detail of my assighment made him unaware that he never took a serious puff on the bloody cigarette. I think the cigarette was his “prop” so to speak, his way of creating obstacles that tested my concentration on what he was saying. In other words, Hall was indirectly teaching me to block out any external distractions when doing my music, even when faced with a comedic situation like wondering when the cigarette ashhes would fall on the upright keyboard or even on his tie. Yes, Hall wore a tie, and a shirt and a jacket. All memories of Hall Overton by his former students 9 times out ot 10 begin with the Ashes to Ashes situation. A champion chain smoker and indeed, a master ash flickerer, never once dirtying the floor, piano or his professorial attire.

Hall Overton, composer, jazz pianist, advocate/activist for the New Music of his time and a lover of Theolonius Monk’s music, was my teacher for one year beginning in 1957. I first heard about him from a fellow classmate at the Manhattan School of Music, which at that time was located on East 103rd street, between 2nd and 3rd avenue, an area then known as Spanish Harlem. This chap was playing in one of the basement practice rooms where I heard him playing Duke Jordan’s “Jordu”. I liked what I heard so much so I asked him where he learned to play that way. Hall Overton, was his reply. I took down Hall’s number, called him and said I wanted to take jazz piano lessons. He sounded warm and gracious over the phone which made me feel relaxed because I was nervous about playing for him. I had been playing jazz gigs and casuals since my teens but still felt light years away from my vision of myself as a complete jazz pianist. Hall was going to push the envelope. We set up weekly lessons.

Continue reading ‘Learning jazz improvisation’

A salute to Dot Crowe and Kewpie Harris

In my teens, I played the church organ for wedding ceremonies, receptions, etc. For this I had the significant help of an elderly spinster lady, Miss Dorothy (“Dot”) Crowe, who also played the organ and piano. She lent me music, gave me performance and business tips, referred clients on to me, and, at one point, advised me to increase my fees to increase the demand for my services. My first of many experiences of the failure of mainstream economic theory was that demand for organ-playing services increased with price – the more I charged, the more business came my way. I learnt that potential customers, who did not know one organist from another (even if they had heard them each play), used price to judge quality: charging lower than my competitors, as I did initially, meant that I was assumed to be not as good or not as reliable an organist as they. It was very nice of Dot Crowe, who was after all also a competitor, to tell me of this.

As far as I knew at the time, Miss Crowe, who was then aged somewhere between 60 and 75, had spent all her life quietly and staidly playing the church organ for Sunday mass and for local weddings. Recently, however, I discovered that she had had an earlier career as a swing band pianist. According to Col Stratford’s oral history of jazz on the Far North Coast of New South Wales, Australia (see reference below), by 1938 Dot Crowe was a band member of Aub Aumos’s band, The Nitelites (photo, page 47). She later led her own band, Dot Crowe and the Arcadian Six. I am stunned to learn this about her, and my admiration, which was already high, now reaches the skies. I never knew she had had this experience when I knew her, and now, of course, it is too late to ask her about it.

The Far North Coast of New South Wales was an epicentre of early jazz in Australia, largely due to the energy and influence of one man: David Samuel (aka “Kewpie”) Harris. Kewpie Harris arrived in Ballina in 1919, aged about 27, apparently selling suitcases. He died, mostly forgotten, in Brisbane in 1981. His nickname arose apparently because his youthful face was open and wide-eyed, like that of a Kewpie Doll. Harris had been born in Britain, and as a schoolboy was a chorister at St Paul’s and St. Stephen’s churches in London. As a teenager, he was a member of the orchestra of Tom Worthington in their regular gig at the Holborn Restaurant, London. For a time he worked in San Francisco, and also played in dance bands on the steamships of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s West Coast fleet. By 1913, he was in Australia and had formed a dance band in North Sydney, and played violin with symphony orchestras and ensembles in Sydney. (As a violinist in Sydney before WW I, he presumably knew Alfred Hill, Australian composer and violinist, and, earlier, a player with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra.)

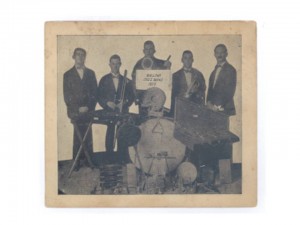

According to family lore, Harris learnt jazz from black American musicians he met on his travels. Upon arrival in Ballina, Harris helped create the Ballina Jazz Band with several other players, including my grandfather and great-uncle. The original members of the band were: Rex Gibson on piano, Harris on violin, saxes, and keyboard percussion (originally marimba and xylophone, and later vibes), Harry Holt on trombone, Charles McBurney on trumpet, and Tom McBurney on drums. Harris then led jazz bands with regular gigs in Northern NSW till 1951, when he left to join the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Between 1936 and 30 January 1950, he managed the Riviera Cabaret, a popular dance hall in Lismore NSW, where his wife acted as hostess and his band, the Kewpie Harris Band, was resident.

Why was jazz so strong in that part of Australia? Partly, perhaps, because Ballina, at the mouth of the Richmond River, was a major trading port – until rail replaced shipping as the main form of freight transport to and from the region, and within the region. Ports have lots of visitors, interested in entertainment and with free time and cash. Partly also, because the area hosted a US Air Force base during WW II (just down the coast, at Evans Head). With the end of the war in the Pacific, and the arrival of television to Australia (in 1956), weekly dances declined in popularity, and no longer regularly attracted the hundreds or thousands that dances even at tiny river ports like Bungawalbyn and Woodburn once did. Dance bands all but disappeared. I guess that good, entrepreneurial jazz musicians were forced to join classical orchestras or to play Mendelssohn’s Wedding March for people with their minds on other things, and spend their evenings remembering what great fun they had once had, and given.

FOOTNOTE (added 2010-08-18): The Kewpie Harris Band is also mentioned in this history of Lismore’s Crethar’s Wonderbar, home of the world-famous Crethar hamburger, as the House band of the Riviera Hotel in Lismore. A descendant of Harris’ band is the recently reformed Northern Rivers Big Band (for which, in its earlier incarnation, my father played). See here.

The photo shows the Ballina Jazz Band in 1919. Players were (left to right): Tom McBurney, Harry Holt, Kewpie Harris, Charles McBurney, and Rex Gibson.

References:

Julia Buchanan [1982]: “Bandleader died a forgotten figure.” The Northern Star. Lismore, NSW, Australia. 6 January 1982, page 50.

Interview with Tom McBurney [1977-01-11] in The Indonesian Observer, reported in Stratford [1990].

Colin Stratford [1990]: From The Stage. Lismore, NSW, Australia. ISBN: 0-9594070-2-2.