Brian Dillon reviews a British touring exhibition of the art of John Cage, currently at the Baltic Mill Gateshead.

Two quibbles: First, someone who compare’s Cage’s 4′ 33” to a blank gallery wall hasn’t actually listened to the piece. If Dillon had compared it to a glass window in the gallery wall allowing a view of the outside of the gallery, then he would have made some sense. But Cage’s composition is not about silence, or even pure sound, for either of which a blank gallery wall might be an appropriate visual representation. The composition is about ambient sound, and about what sounds count as music in our culture.

Second, Dillon rightly mentions that the procedures used by Cage for musical composition from 1950 onwards (and later for poetry and visual art) were based on the Taoist I Ching. But he wrongly describes these procedures as being based on “the philosophy of chance.” Although widespread, this view is nonsense, accurate neither as to what Cage was doing, nor even as to what he may have thought he was doing. Anyone subscribing to the Taoist philosophy underlying them understands the I Ching procedures as examplifying and manifesting hidden causal mechanisms, not chance. The point of the underlying philosophy is that the random-looking events that result from the procedures express something unique, time-dependent, and personal to the specific person invoking the I Ching at the particular time they invoke it. So, to a Taoist, the resulting music or art is not “chance” or “random” or “aleatoric” at all, but profoundly deterministic, being the necessary consequential expression of deep, synchronistic, spiritual forces. I don’t know if Cage was himself a Taoist (I’m not sure that anyone does), but to an adherent of Taoist philosophy Cage’s own beliefs or attitudes are irrelevant to the workings of these forces. I sense that Cage had sufficient understanding of Taoist and Zen ideas (Zen being the Japanese version of Taoism) to recognize this particular feature: that to an adherent of the philosophy the beliefs of the invoker of the procedures are irrelevant.

In my experience, the idea that the I Ching is a deterministic process is a hard one for many modern westerners to understand, let alone to accept, so entrenched is the prevailing western view that the material realm is all there is. This entrenched view is only historically recent in the west: Isaac Newton, for example, was a believer in the existence of cosmic spiritual forces, and thought he had found the laws which governed their operation. Obversely, many easterners in my experience have difficulty with notions of uncertainty and chance; if all events are subject to hidden causal forces, the concepts of randomness and of alternative possible futures make no sense. My experience here includes making presentations and leading discussions on scenario analyses with senior managers of Asian multinationals.

We are two birds swimming, each circling the pond, warily, neither understanding the other, neither flying away.

References:

Kyle Gann [2010]: No Such Thing as Silence. John Cage’s 4′ 33”. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press.

James Pritchett [1993]: The Music of John Cage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Archive for the ‘Art’ Category

Page 6 of 7

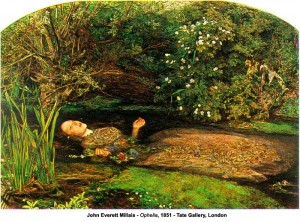

Lady Ophelia of Old Malden

News today that an amateur art-historian, Barbara Webb, has identified the location which pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais used as background for his 1851 painting of the drowned Ophelia. The location is on the Hogsmill River at Old Malden in south London. It’s a long way from Elsinore.

The after-life of this image has been immense, at least in the English-speaking world. For instance, a print of the painting appears on the wall of the room rented by George Eastman, the humble protagonist of George Stevens’ 1951 movie, A Place in the Sun, a film of Theodore Dreiser’s novel, An American Tragedy. I took the presence of the print on Eastman’s wall not only as prophecy of the tragedy to come, but also as a reference to Hamlet, since Eastman, as he is played by Montgomery Clift, is undecided between his two lovers and the two very different fates which his involvement with them entails.

Spiderwoman RIP

The death has occurred of artist Louise Bourgeois, aged 98. I can’t say I liked or appreciated her art at all, most of which I found unsettling, sinister and off-putting. Her art did not communicate anything pleasant or subtle, at least not to me, but perhaps that was her intention, or else I was not in her target audience. Her art was also obsessive (all those spiders, for goodness sake!) and very literal-minded (every one of them with exactly 8 legs). Somehow we expect our artists, of all people, to have more imagination than this. Bourgeois appears to have been true to her own vision and to her own self, but that does not mean she was someone I would want to spend any time with.

Perhaps I was not the only person repelled by her art and the personality it revealed. In gallery Dia: Beacon, upriver from New York City, Bourgeois’ art is placed in a small upstairs room on its own, hidden away from the other work like some Mrs Rochester of the art world. Perhaps the curators thought her work would infect the wonderful minimalist and conceptual art for which the gallery is rightly known; her work certainly seems out of place in this gallery. As elsewhere, I found her art there unpleasant, and a whole room full was overwhelmingly repellent. Indeed, the one great work in that room you only see as you descend the steps to leave, and is not by her or by any artist. In this former printing factory, the wall next to the steps is the original external red-brick factory wall, covered in some places with a white dust, and left as it presumably was when the gallery took over the building. This subtle, spiritual wall with its geometric pattern of red bricks overlaid with random splotches of white is the only interesting or pleasant artwork in the Bourgeois room at Dia:Beacon. It says something about Bourgeois’ art (or perhaps about my taste) that the packaging here is much better art than any of the objects inside it.

Copy me, I'm on my way out

Cosma Shalizi at Three-Toed Sloth cannot understand why people desire original works of visual art rather than printed reproductions, especially when we’ve been buying printed books rather than manuscript codexes for centuries now. He presents – and demolishes too quickly, I believe – some potential reasons for this. I am very surprised by his view, but perhaps its the sheltered life I lead.

First, let me say as a computer scientist, that a map is not the territory. It is easy to confuse a representation of some object with that object itself, and the people now singing the praises for e-books seem to be doing just that. Au contraire, I believe that hard, physical books will continue to be purchased and kept yet for hundreds of years, and possibly many more years, because books are souvenirs of our experience of reading them. The same is true of works of visual art. If you have had some hand in the commissioning, the creation (for example, as subject of the artwork or as patron of the artist), or the selection and purchase of a work of art, you want the work of art itself, not a copy, to remind yourself of that experience.

Second, let me say as a former mathematician, that printed reproductions of artworks are projections onto 2 dimensions of 3-dimensional objects. By definition, such projections will lose something. If you think that what is lost thereby in visual art is unimportant, as Cosma seems to, then you’ve not been looking very closely at real paintings or drawings. There are too many examples to recount, so let me just point to: the brush-strokes in JMW Turner’s seascapes, which manifest and convey the torment of the scenes (and that of the painter); or the drip effects in Jackson Pollock’s action paintings, which likewise manifest and convey the energy of the creation process; or the careful, visible brushwork of the leaves and blades of grass in Pre-Raphaelite art or in the art of the Yangzhou painters of the early Qing Dynasty; or the brush-strokes in Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. These effects are either invisible or can barely be seen in printed reproductions. It is also worth noting that Chinese art has, for hundreds of years, supported “factory production” of 3-D paintings, using lesser-skilled artists to make approved copies of paintings by famous artists, usually under the direct, personal supervision of the famous artist him or herself; that these copies are purchased rather than printed reproductions indicates that the 3-D object has qualities perceived to be lacking in any 2-D print.

Third, let me say as a former statistician, that it seems to be easy for people familiar with Andrei Kolmogorov’s theory of complexity to imagine they have represented faithfully some object, when all they have captured is its surface form (its syntax). As I have argued before, the canonical example used in discussions of algorithmic complexity is Kazimir Malevich’s painting Black Square, which is alleged to be easy to reproduce with an algorithm such as:

Paint a pixel of black in each pixel throughout the square.

At best what this algorithm generates is a copy not of the 3-dimensional painting itself, but of a 2-dimensional projection of it. But even were it to recreate the 3-D object, such an algorithm ignores the meaning of the painting and the historical context of its creation – in linguistic terms, its semantics (or its use-context-independent meaning) and its pragmatics (its use-context-dependent meaning). Both these aspects are immensely important to understanding and appreciating the work, and for explaining why it appeared when it did and not before, and understanding its reception and influence. As I noted before, one can just about imagine the 18th-century Welsh landscape painter Thomas Jones eventually creating something similar to Black Square, since he painted contemplative, Zen-like depictions of seemingly-featureless Neapolitan walls (such as A Wall in Naples, pictured above), but no other artist before Malevich.

How is this relevant? Well, once you’ve seen and admired Malevich’s painting, no printed reproduction would satisfy you for an instant.

Finally, paintings – even when traditional, representational art – are best understood, not as representations of objects or scenes or feelings or indeed of anything at all, but as attempts at solutions to problems in painting. Most solutions fail, so the artist abandons that attempt, and tries again. In the meantime, the abandoned partial solution may provide pleasure and joy (or other responses) to those who view it, and to those who seek to emulate the methods of its painting which a careful study of it may disclose. (The thoughts of Marion Milner are relevant here, especially regarding the quaint idea that artists make art to express some pre-existing emotion.)

FOOTNOTE: The post title is a reference to an Ambitious Lovers song.

Maps and territories and knowledge

Seymour Papert, one of the pioneers of Artificial Intelligence, once wrote (1988, p. 3), “Artificial Intelligence should become the methodology for thinking about ways of knowing.” I would add “and ways of acting”.

Some time back, I wrote about the painting of spirit-dreamtime maps by Australian aboriginal communities as proof of their relationship to specific places: Only people with traditional rights to the specific place would have the necessary dreamtime knowledge needed to make the painting, an argument whose compelling force has been recognized by Australian courts. These paintings are a form of map, showing (some of) the spirit relationships of the specific place. The argument they make is a very interesting one, along the lines of:

What I am saying is true, by virtue of the mere fact that I am saying it, since only someone having the truth would be able to make such an utterance (ie, the painting).

Another example of this type of argument is given by Rory Stewart, in his account of his walk across Afghanistan. Stewart does not carry a paper map of the country he is walking through, lest he be thought a foreign spy (p. 211). Instead, he learns and memorizes a list of the villages and their headmen, in the order he plans to walk through them. Like the aboriginal dreamtime paintings, mere knowledge of this list provides proof of his right to be in the area. Like the paintings, the list is a type of map of the territory, a different way of knowing. And also like the paintings, possession of this knowledge leads others, when they learn of the possession, to act differently towards the possessor. Here’s Stewart on his map (p. 213):

It was less accurate the further you were from the speaker’s home . . . But I was able to add details from villages along the way, till I could chant the stages from memory.

Day one: Commandant Maududi in Badgah. Day two: Abdul Rauf Ghafuri in Daulatyar. Day three: Bushire Khan in Sang-izard. Day four: Mir Ali Hussein Beg of Katlish. Day five: Haji Nasir-i-Yazdani Beg of Qala-eNau. Day six: Seyyed Kerbalahi of Siar Chisme . . .

I recited and followed this song-of-the-places-in-between as a map. I chanted it even after I had left the villages, using the list as credentials. Almost everyone recognized the names, even from a hundred kilometres away. Being able to chant it made me half belong: it reassured hosts who were not sure whether to take me in and it suggested to anyone who thought of attacking me that I was linked to powerful names. (page 213)

Because AI is (or should be) about ways of knowing and doing in the world, it therefore has close links to the social sciences, particularly anthropology, and to the humanities.

References:

Seymour Papert [1988]: One AI or Many? Daedalus, 117 (1) (Winter 1988): 1-14.

Rory Stewart [2004]: The Places in Between. London, UK: Picador, pp. 211-214.

Bridget Riley on drawing as thinking

Ealier, I quoted Marion Milner on the zen of sunday-painting. The British artist, Bridget Riley, writing for a catalog that accompanied a retrospective of her work presented recently at the Walker Gallery in Liverpool, UK, talks about the non-propositional thinking involved in drawing and painting, particularly during the exploration that she undertakes as she begins each new work.

For me, drawing is an inquiry, a way of finding out – the first thing that I discover is that I do not know. This is alarming even to the point of momentary panic. Only experience reassures me that this encounter with my own ignorance – with the unknown – is my chosen and particular task, and provided I can make the required effort the rewards may reach the unimaginable. It is as though there is an eye at the end of my pencil, which tries, independently of my personal general-purpose eye, to penetrate a kind of obscuring veil or thickness. To break down this thickness, this deadening opacity, to elicit some particle of clarity or insight, is what I want to do.

The strange thing is that the information I am looking for is, of course, there all the time and as present to one’s naked eye, so to speak, as it ever will be. But to get the essentials down there on my sheet of paper so that I can recover and see again what I have just seen, that is what I have to push towards. What it amounts to is that while drawing I am watching and simultaneously recording myself looking, discovering things that on the one hand are staring me in the face and on the other I have not yet really seen. It is this effort ‘to clarify’ that makes drawing particularly useful and it is in this way that I assimilate experience and find new ground. (p. 15). . .

You cannot deal with thought directly outside practice as a painter: ‘doing’ is essential in order to find out what form your thought takes. The ‘new curves’ that I started in 1998 grew directly out of paintings such as Shimmered Shade. The latent visual arcs and sweeping movements came to the fore in Painting with Verticals 1 (2006) and Red with Red 1 (2007). Retaining the diagonals and verticals of the earlier group of paintings, I introduced a curve that connected to the existing structure. This is the underpinning of my new curvilinear work. The vertical is still there, acting like a break in the movement across the canvas. The cut collage pieces define the various contours that arise from combining and recombining the slender curve with its diagonal accents. This has developed into a layering technique that allows me to weave forms and colours together in a supple plastic space. I have reduced the number of colours and increased the scale of the imagery. Would it be possible to once again build up a repertoire of these invented forms, a repertoire that might gradually acquire sufficient momentum to put itself at risk, to precipitate its own kind of hazard? It is only through the experience of working that answers may be discovered within the inner logic of an invented reality such as the art of painting.” (p. 18)

References:

The image is Red with Red by Bridget Riley, 2007.

Bridget Riley [2009]: Work. pp. 15-18 of: Michael Bracewell and Bridget Riley [2009]: Bridget Riley Flashback. London, UK: Hayward Publishing.

This essay was republished in The London Review of Books (31 (19): 20-21, 8 October 2009) and is online here.

Theatre Lakatos

Last night, I caught a new Australian play derived from the life of logician Kurt Godel, called Incompleteness. The play is by playwright Steven Schiller and actor Steven Phillips, and was peformed at Melbourne’s famous experimental theatrespace, La Mama, in Carlton. Both script and performance were superb: Congratulations to both playwright and actor, and to all involved in the production.

Godel was famous for having kept every piece of paper he’d ever encountered, and the set design (pictured here) included many file storage boxes. Some of these were arranged in a checkerboard pattern on the floor, with gaps between them. As the Godel character (Phillips) tried to prove something, he took successive steps along diagonal and zigzag paths through this pattern, sometimes retracing his steps when potential chains of reasoning did not succeed. This was the best artistic representation I have seen of the process of attempting to do mathematical proof: Imre Lakatos’ philosophy of mathematics made theatrical flesh.

There is a photograph of the La Mama billboard at Paola’s site.

The Zen of Sunday-painting

In his famous account of learning the piano as an adult, Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger refers to a book by psychiatrist, Marion Milner, a pseudonym of Joanna Field. Milner was the sister of Nobel-physicist Patrick Blackett, and great-neice of Edmund Blackett, the architect of colonial Sydney. Her book is an account of her attempts to paint and draw, and to learn to paint and draw, as an amateur artist.

I am not enchanted by her artwork, and I find her Freudian accounts of artistic creativity and its barriers both implausible and untrue to life. I believe Alfred Gell’s anthropological account of art to be far more compelling – that artworks are tokens or indexes of intentionality, perceived by their viewers or auditors as objects created with specific intentions by goal-directed entities (the artist, or a community, or some spiritual being). These perceived intentions include much else beside the expression of feelings.

But Milner’s book is replete with some wonderful insights, many of which express a Zen sensibility. Herewith a sample:

Continue reading ‘The Zen of Sunday-painting’

With the Brotherhood against Germaine

Although born a Melbournite and raised a Catholic, Germaine Greer, while she was a post-graduate student at Sydney University, was a late child of one of Australia’s Bohemian moments, The Push. How odd, then, that she should take against that earlier group of Bohemian artists, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

In her Guardian column, Germaine Greer first criticizes the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) for not being original as artists, since their style resembles that of the slightly earlier German Nazarenes. I question the fairness of such a criticism for art made in the days before public art collections, colour photography, satellite TV, and international blockbuster exhibitions. But at least from this we know that she values originality in art over other criteria, and thus reveals herself captive to that insidious idea which has held most of our cultural critics hostage these last two centuries: that only those with something new to express should be permitted to make art. Nice to see you using your own critical faculties there, Dr Greer, and not just swimming with the art-critical tide.

She goes on to say:

It will be obvious to many that, while France was experiencing the dazzle of the impressionists, Britons were happy to applaud and reward the false sentiment, fancy dress and finicking pseudo-realism of a dreary horde of pre-Raphaelites.

The PRB led its followers into a welter of truly bad art: stultified, inauthentic, meretricious and vulgar. Where the Nazarenes went for luminosity, simplicity and piety, the PRB wallowed in elaboration, erotic suggestion and overheated colour. If they hadn’t had sex with their models, they wanted you to think they had. They realised pretty early on that nudes are not erotic; their languorous models drooped, swooned, gasped and died in ever more elaborate, flowing gowns shot through with new synthetic colours: arsenic greens, cobalt blues, alizarin crimsons.”

We learn that she does not like their art. But the justification of her taste leaves a lot to be desired. The art of the PRB is both “dreary” and uses “overheated colours”. How exciting to find an English text by a writer as good as this where precisely one, but only one, of two adjectives is used with the opposite of its usual meaning. But which one? Clearly, her writing is testing our wits here – challenging us to find a version of reality which enables both these conflicting descriptions to be simultaneously true of the same art.

The percipient Dr Greer clearly doesn’t like bright colours, although (as one might expect from someone with a PhD in EngLit) she enjoys finding the precise words to denote them: “arsenic greens, cobalt blues, alizarin crimsons”. Nicely put, and not merely the three primary colours, either. But one does not need the advice of a professional art critic to decide whether one likes certain colours or not. Any child can do that. And nothing provided by the indefatigable Dr Greer justifies – or could ever justify – her individual, peculiar preference here, because colour preference is entirely a matter of personal taste (itself perhaps partly of biology, for the colour blind), and not of art theory or art criticism or even of art newspaper mongering. I find the PRB’s colours and colour combinations riveting, electric and enchanting.

Consider some of those other adjectives the irrepressible Dr Greer applies: “false sentiment”, “inauthentic, meretricious”. How, precisely, does one determine that a work of visual art is inauthentic or meretricious? Oh, I am sure one can do this with literature: a writer’s choice of words may reveal his or her true thoughts even when the surface description is pointing elsewhere. The novel, The Godfather, by Mario Puzo, for example, seems to show a writer reveling in the violence which his own text ostensibly deplores. But those arts which do not use language – visual art, music, dance, etc – have a murkier connection to the world they inhabit, and they do not have this capacity for self-reference and hence self-revelation. So how can the good Doctor actually determine the authenticity or otherwise of a painting? Perhaps by comparing its subject with its treatment, for example if a serious scene were painted in a slapdash manner, or the reverse. But against such an argument, one could just as easily argue that the means do not necessarily vitiate the ends, but instead may empower or ennoble them: ie, a careful, finicky, technically-adept painting of an apparently flippant subject could actually enhance the subject and bring it to our attention, as in Mozart’s operas with their silly plots or those Haydn symphonies containing musical jokes or even Duchamp’s Fountain. Or indeed, with the PRB’s careful, elaborated, and finely-accurate paintings of imagined scenes from myth and history. No, arguing the inauthenticy of visual art would only ever be persuasive if done painting-by-painting, and even then would need greater intellectual subtlety, depth and heft than the inestimable Dr Greer has chosen to provide here.

Pre-Raphaelite art, for reasons unclear to me, has almost always been unpopular with art critics. Depending on which historical era you select, art critics of the time have tended to believe that all art should celebrate us, or uplift us, or provoke us to thought, or confront us, or even attack us. Almost never have art critics wanted art merely to entertain us, to give pleasure to us, to be enjoyed by us. One has to ask what is wrong with a profession so opposed to simple beauty and pleasure. And what does our Germaine think? Well, she describes the PRB’s art as “vulgar”. Now this is a very interesting adjective, and in this word I believe we have found the deep ground of her dislike. This word is usually used to refer to objects and activities which are popular, which ordinary people do or which they enjoy, but of which the person deploying the word disapproves. That one word “vulgar” gives her game away. It is a word heard often by anyone having an Australian Convent education. And it is certainly indicative of the irony-rich subtlety of Greeresque thought that this word should be deployed by someone who has appeared on reality TV.

By an accident of historical timing, one of the great world collections of Pre-Raphaelite art is in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in Sydney. I have no way of knowing if that collection and her time in Sydney and in The Push are connected to her present dislike of this great, technically-sophisticated, life-affirming, ennobling, and pleasing art. By the very same accident of timing (local people made good, collecting the latest in British art when the PRB were active), the other great world collections of Pre-Raphaelite are in the northwest of England, particularly the Walker Gallery in Liverpool, the Lady Lever Gallery in Birkenhead, and Manchester City Art Gallery.

Belligerent musical ignorance

Via Tom Service, I learn of a new blog seeking to define classical music in such a way as to exclude anything the writers do not themselves like.

I wonder, first, what is the point. Why can’t people be happy with their own preferences, their own choices, and leave other people to be happy also with their respective preferences and choices? What deep sense of anxiety or profound inferiority leads people so often to try to force others to make the same aesthetic choices as themselves, or, if unable to force that, to disparage the choices of others? There has to be something profoundly wrong with a person’s aesthetic philosophy or with their psyche if they undertake rule-mongering in order to defend their own preferences.

Second, seeking to include only the music they like and to exclude the remainder, the writers of this new blog present an axiomatization for what they refer to as “Art Music”. They use the term Art Music, but I think Autistic Music would be a better fit. Putting aside the cultural assumptions inherent in undertaking axiomatizations (something for another post), let’s examine their proposed axioms (numbered for ease of reference). I first list the axioms and then I interpolate my responses.

To count as Art Music, a work must meet ALL* the following criteria:

1. It must be written for acoustic instruments and/or unamplified voices (mechanical and electr(on)ic devices may also be employed for textural effect)

2. It must be the original work of a single author (texts notwithstanding)

3. It must be preserved and transmitted as a score, written in orthodox musical notation, alterable only by the composer (unless the composer dies before completion)

4. It must stand on, or peer over, the shoulders of giants, i.e. acknowledge, build on or work from 1000 years of fundamentally accumulative history from the so-called Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic and Modern (see right) eras (or their equivalents in non-Western cultures)

5. It must be conceived for performance according to the instructions and faithful to the intent of the composer (performers always following the score precisely in as much detail as the composer provides; improvisations and ornamentations permitted where the composer allows or expects)

6. It must be musically and intellectually complex, coherent and sophisticated, i.e. display and encode, in various permutations, originality, discursiveness, subtlety, intricacy, symbolism, logic, humour etc through the use (in various combinations) of development-over-time (through-composition), advanced harmony, modulation, variation, variance of musical phrase length, counterpoint, polyphony etc. It will therefore:

6.1 Require a high level of musicianship (concentration, insight, accomplishment) on the part of performers, who must draw on musical education, personal experience and imagination, knowledge of a work’s idiom, and the accumulated body of historical performance practices even for a merely competent performance

6.2 Require relatively high levels of concentration, understanding and competence from listeners for appreciation and (even basic) comprehension

6.3 Be susceptible to detailed theoretical analysis

7. It must aspire to provide the listener with emotional and intellectual enjoyment and satisfaction, by communicating through musical complexity, sophistication and coherence exceptional and/or transcendent reflections on the human condition

In reality this is an anti-modern, anti-jazz, anti-downtown, anti-world music, anti-rock, anti-pop, anti-folk, anti-hip hop manifesto. Most of the music excluded is music by non-white peoples. Perhaps it is just a coincidence that the music which passes these rules is mostly written by dead, white, European males, or perhaps the authors really are the racists that these rules would suggest.

It is hard to know where to start with such an absurd list, so let us proceed in order.

1. It must be written for acoustic instruments and/or unamplified voices (mechanical and electr(on)ic devices may also be employed for textural effect)

First the restriction to written texts (#1, #3) excludes all of improvised music – that’s music by people like Bach, Buxtehude, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, etc, not to mention jazz, klezmer, gypsy, indian music, gamelan, etc.

Axiom #1 also requires that mechanical and electronic instruments only be used for textural effects. There goes the organ repertoire! Baroque organs were perhaps the most sophisticated mechanical devices in the pre-modern era, and the large ones required at least two human operators – one person to play the keyboards and one or more to pump the bellows. And every modern trumpet, cornet, French Horn, tenor horn, euphonium and tuba uses a mechanical device called a valve, while Bb/F trombones use a switch to change from tenor to bass. So all the brass repertoire since about 1800 disappears too. And, indeed, keyboard instruments like the harpsichord and the piano use mechanical devices to transfer action executed by the performer to actions executed by the instrument. Even the sound and the means of performance of string instruments have been changed with new technologies, such as new materials for bows and the invention of shoulder-rests. A violin shoulder rest, for instance, means the left-arm of the violinist is no longer required to maintain the violin in position under the player’s chin. That in turn means the performer’s left hand can zip up and down the finger board with far greater rapidity and flexibility. The 19th and 20th century violin repertoire would be mostly unplayable without shoulder rests.

The irony in using a web-page to argue for acoustic instruments seems to have escaped these authors. I honestly don’t understand the mentality of people who favour so-called acoustic instruments. The instrument with the cleanest interface between human action and sound output is undoubtedly the theremin, where the performer touches nothing, and merely (after long practice!) waves his or her hands in the air. Technologically, this instrument is as unsophisticated as stone-age fire in comparison to the sophistication involved in the design, construction and maintenance of a modern piano or, for that matter, a baroque organ. So an intellectually-coherent set of musical axioms could hardly include the piano while excluding the theremin – unless there is something immoral about using electricity to aid sound production.

But in that case (as I have long argued contra to the authentic performance movement), why perform in air-conditioned halls lit by electric light? If you limit yourself to acoustic instruments, then surely intellectual consistency would require performance in halls or rooms without any other modern convenience. The actual sound – as produced by the musician, and as perceived by the listener – will be influenced by the ambient temperatures in the performance venue. If you think this comment is a trivial one, then you have never played a brass instrument in a cold hall or outside on a winter’s day.

2. It must be the original work of a single author (texts notwithstanding)

Axiom #2 requires that the work be single-authored. What of Bach’s reworking then of Vivaldi’s music? What of Gounod’s “Ave Maria”, a melody famously set to a prelude by Bach? I rather like that setting, as indeed I expect the authors of these axioms would. Axiom #2 also excludes most of jazz, world music, rock, etc.

3. It must be preserved and transmitted as a score, written in orthodox musical notation, alterable only by the composer (unless the composer dies before completion)

The restriction to orthodox notation (#3) excludes some of the greatest music of the last 50 years, which is perhaps the authors’ intention. But what of figured bass notation? Is this traditional? It was once, but has not been so much used these last 150 years. Since its use implies an improvisational stance to music, perhaps its loss is also

intentional (as per #1).

But anyway, what is so special about orthodox notation? Elsewhere on the site, the authors say they aim “to repudiate cultural relativism in music”. But what is more culturally-relative than musical notation? The standard notation we use in the west today is culturally and historically-specific. It is by no means the only notation. It is not even necessarily the best notation – it fails, for example, to adequately represent divisions of the octave into other than 12 pitch-classes; it does not deal well with unequal temperament or with dynamic pitches or with polyrhythms or allow precise gradations of dynamics; it ignores timbre; it mostly overlooks sound production (ask Morty Feldman about that!) and it is harder to learn than some other notations (eg, popular guitar chords symbols), etc. Like any system of representation of human knowledge it has strengths and it has weaknesses. But these authors proclaim “Art Music is in many ways objectively superior to Pop ‘Music’ “ and yet insist on using a culturally-specific notation with known weaknesses.

4. It must stand on, or peer over, the shoulders of giants, i.e. acknowledge, build on or work from 1000 years of fundamentally accumulative history from the so-called Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic and Modern (see right) eras (or their equivalents in non-Western cultures)

Well all music (and indeed all art) does this, even when it ignores the giants. This axiom reveals the ignorance of the authors, since even their hated pop musicians “build on or work from” the music of their predecessors. And here suddenly here we have an allowance for non-Western music. Most of these musics were excluded by Axioms 1 (which requires music to be “written”) and 2, so including them here would seem to be just some weak attempt to prove the authors are not racists after all. Nothing in the other axioms would lead one to think that the authors really like or understand, for example, Javanese gamelan or Shona mbira music, or perhaps even know what they are.

5. It must be conceived for performance according to the instructions and faithful to the intent of the composer (performers always following the score precisely in as much detail as the composer provides; improvisations and ornamentations permitted where the composer allows or expects).

Oh dear. Here and in Axiom #3 we have the romantic fallacy that performing musicians are mere slaves to the will of the god-composer. Have none of the authors ever listened to Chopin’s music? Almost every performer of Chopin’s solo piano music — INCLUDING CHOPIN HIMSELF – plays with rubato, an elongation and compression of time, like a natural breathing, rather than a rigid adherence to a beat. None of this breathing is marked on the score, but is always and everywhere decided by the performer, as if on-the-fly.

But the performer is only part of the story. A musical work also requires an audience. It is the complete trio – composer, performers, audience – who interpret a piece of work, not any one of the three. Go read the books of Mark Evan Bonds to see how crucial the audience is for understanding the meaning of a musical work, and understanding how it should be read and performed. The ignorance the authors reveal here of western music history – ie, the history of the very music the authors claim to be promoting – is simply stunning.

6. It must be musically and intellectually complex, coherent and sophisticated, i.e. display and encode, in various permutations, originality, discursiveness, subtlety, intricacy, symbolism, logic, humour etc through the use (in various combinations) of development-over-time (through-composition), advanced harmony, modulation, variation, variance of musical phrase length, counterpoint, polyphony etc. It will therefore:

Well, all music is “musically and intellectually complex, coherent and sophisticated”. Because the authors first require “advanced harmony”, I suspect the intent here is to exclude minimalist, downtown and rock music. If the authors think that any of these musics is not complex and sophisticated, they are simply not listening. (It is something truly strange to ponder why so many trained uptown musicians can hear downtown or pop or non-western music without actually listening to it; I guess the answer is in their training.)

The complexities in these musics often lie in places elsewhere than in music in the main thread of western classical music — for example, in the interplay of multiple, intersecting rhythms rather than in harmonies. But complexities there certainly are. If you limit yourself to music which is only harmonically complex, for example, you’d also have to forget the pre- and early-Baroque, along with 20th century composers like Shostakovich, Orff, Satie, or the Ravel of Bolero. Of course, you’d get all the Wagner you could possibly want, although that trade would not satisfy me at all.

6.1 Require a high level of musicianship (concentration, insight, accomplishment) on the part of performers, who must draw on musical education, personal experience and imagination, knowledge of a work’s idiom, and the accumulated body of historical performance practices even for a merely competent performance

See comment to #6.

6.2 Require relatively high levels of concentration, understanding and competence from listeners for appreciation and (even basic) comprehension

See comment to #6.

6.3 Be susceptible to detailed theoretical analysis

See comment to #6. Anyone who thinks that popular music, for example, is not susceptible to detailed theoretical analysis, is simply ignorant.

7. It must aspire to provide the listener with emotional and intellectual enjoyment and satisfaction, by communicating through musical complexity, sophistication and coherence exceptional and/or transcendent reflections on the human condition

See comment to #6.

The contemptible views expressed on the site are very similar to those I’ve heard expressed before by uptown composers such as Harrison Birtwistle. Is this website the uptown response to downtown and popular music? Shoot-out at autistic musical gulch, perhaps? It is hard to imagine that people with such views still exist, let alone that they have heard of the web. But that is enough dragon-slaying for now. I will sure have to more to say in a future post.

Update (2018-03-25): The site was musoc.org, but it now seems to have disappeared.

References:

Mark Evan Bonds [2006]: Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.