On 22.00 on Monday 4 August 2014, Ryoji Ikeda turned-on an installation of a vertical light at Westminster, entitled Spectra, to commemorate the centenary of the entry of Britain into World War I. The light can be seen from many places elsewhere in central London, appearing to curve over the viewer and ending in a burst of brightness. The effect is ominous and hauntingly beautiful, particularly in the early hours of the morning when alone on the streets.

Archive for the ‘Art’ Category

Page 3 of 7

The Lamberts

From sometime before 1933 right down to the present day, members of my family have had on their walls reproductions of George Lambert’s 1899 Wynne-Prize-winning painting Across the Black Soil Plains, and so this image is part of my cultural heritage. (Image due to AGNSW.)

George Washington Thomas Lambert (1873-1930) was an Australian artist born, after his father had died, in St Petersburg of an American father and English mother. The family emigrated to New South Wales in 1887. In Australia, he is most famous for his painting, Across the Black Soil Plains, now in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, which was based on his time living at Warren, NSW. During WWI, he was an official Australian war artist.

George’s son, Leonard Constant Lambert (1905-1951) was a jazz-age British composer and conductor, and co-founder of Sadler’s Wells dance company. Constant’s son, Christopher (“Kit”) Sebastian Lambert (1935-1981) was a record producer and manager, and part-creator of rock band, The Who.

Sad that son and grandson both died in their 46th year.

Visual pleasure

Some buildings and spaces provide pleasure to the eye and heart, and an inexplicable lift to the spirits. One such place is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple in Chicago, whose intimacy and proportions are ineffably balanced.

Another is the Italianate Church of St Brigid in Wavertree, Liverpool. This Anglican church was designed by E. A. (Arthur) Heffer and built between 1868 and 1872. The building can be clearly seen from the inter-city trains approaching and departing Liverpool’s Lime Street station, and seeing it never fails to lift my spirits.

Perhaps the pleasure arises from the stark contrast between the tall bell tower and the flat, surrounding landscape of two-story Victorian terraces. Or perhaps it is the shape and size of the tower; certainly, the visual pleasure would be much less if the tower were pyramid-shaped, or conical, or any shorter.

Auburn addictions

Mrs Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865) writing on the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rosetti (1828-1882), in a letter to Charles Eliot Norton (25 and 30 October 1859). The image that was here showed Rossettti’s painting La Ghirlandata (The Garlanded Lady), for whom the model was Alexa Wilding. Bridgeman Art Library, London.

I went three times to his studio, and met him at two evening parties – where I had good deal of talk with him, always excepting the times when ladies with beautiful hair came in when he was like the cat turned into a lady, who jumped out of bed and ran after a mouse. It did not signify what we were talking about or how agreeable I was; if a particular kind of reddish brown, crepe wavy hair came in, he was away in a moment struggling for an introduction to the owner of said hair. He is not as mad as a March hare, but hair-mad.”

Dissident graffiti in Czechoslovakia

In August 1984, I saw a display of cartoons by Jan Bernat, at the Mustek Metro Station in Prague, CSSR. One cartoon showed a crowd of Western Europeans of various nationalities saying “No”, “Non”, “Nien”, etc, to nuclear weapons, with Ronald Reagan in front of them all and holding a placard saying “YES.”

However, some graffitist had scribbled over Reagan’s “YES” and written “NO.”

Influential Books

This is a list of non-fiction books and articles which have greatly influenced me – making me see the world differently or act in it differently. They are listed chronologically according to when I first encountered them.

- 2024 – Nikki Mark [2023]: Tommy’s Field: Love, Loss and the Goal of a Lifetime. Union Square.

- 2023 – Clare Carlisle [2018]: “Habit, Practice, Grace: Towards a Philosophy of Religious Life.” In: F. Ellis (Editor): New Models of Religious Understanding. Oxford University Press, pp. 97–115.

- 2022 – Sean Hewitt [2022]: All Down Darkness Wide. Jonathan Cape.

- 2022 – Stewart Copeland [2009]: Strange Things Happen: A Life with “The Police”, Polo and Pygmies.

- 2019 – Mary Le Beau (Inez Travers Cunningham Stark Boulton, 1888-1958) [1956]: Beyond Doubt: A Record of Psychic Experience.

- 2019 – Zhores A Medvedev [1983]: Andropov: An Insider’s Account of Power and Politics within the Kremlin.

- 2016 – Lafcadio Hearn [1897]: Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East. London, UK: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company Limited.

- 2015 – Benedict Taylor [2011]: Mendelssohn, Time and Memory. The Romantic Conception of Cyclic Form. Cambridge UP.

- 2010 – Hans Kundnani [2009]: Utopia or Auschwitz: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust. London, UK: Hurst and Company.

- 2009 – J. Scott Turner [2007]: The Tinkerer’s Accomplice: How Design Emerges from Life Itself. Harvard UP. (Mentioned here.)

- 2008 – Stefan Aust [2008]: The Baader-Meinhof Complex. Bodley Head.

- 2008 – A. J. Liebling [2008]: World War II Writings. New York City, NY, USA: The Library of America.

- 2008 – Pierre Delattre [1993]: Episodes. St. Paul, MN, USA: Graywolf Press.

- 2006 – Mark Evan Bonds [2006]: Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. Princeton UP.

- 2006 – Kyle Gann [2006]: Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice. UCal Press.

- 2005 – Clare Asquith [2005]: Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. Public Affairs.

- 2004 – Igal Halfin [2003]: Terror in My Soul: Communist Autobiographies on Trial. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard UP.

- 2002 – Philip Mirowski [2002]: Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science. Cambridge University Press.

- 2001 – George Leonard [2000]: The Way of Aikido: Life Lessons from an American Sensei.

- 2000 – Stephen E. Toulmin [1990]: Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity. University of Chicago Press.

- 1999 – Michel de Montaigne [1580-1595]: Essays.

- 1997 – James Pritchett [1993]: The Music of John Cage. Cambridge UP.

- 1996 – George Fowler [1995]: Dance of a Fallen Monk: A Journey to Spiritual Enlightenment.

Doubleday. - 1995 – Chungliang Al Huang and Jerry Lynch [1992]: Thinking Body, Dancing Mind. New York: Bantam Books.

- 1995 – Jon Kabat-Zinn [1994]: Wherever You Go, There You Are.

- 1995 – Charlotte Joko Beck [1993]: Nothing Special: Living Zen.

- 1993 – George Leonard [1992]: Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment.

- 1992 – Henry Adams [1907/1918]: The Education.

- 1990 – Trevor Leggett [1987]: Zen and the Ways. Tuttle.

- 1989 – Grant McCracken [1988]: Culture and Consumption.

- 1989 – Teresa Toranska [1988]: Them: Stalin’s Polish Puppets. Translated by Agnieszka Kolakowska. HarperCollins. (Mentioned here.)

- 1988 – Henry David Thoreau [1865]: Cape Cod.

- 1988 – Rupert Sheldrake [1988]: The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Habits of Nature.

- 1988 – Dan Rose [1987]: Black American Street Life: South Philadelphia, 1969-1971. UPenn Press.

- 1987 – Susan Sontag [1966]: Against Interpretation. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- 1987 – Gregory Bateson [1972]: Steps to an Ecology of Mind. U Chicago Press.

- 1987 – Jay Neugeboren [1968]: Reflections at Thirty.

- 1985 – Esquire Magazine Special Issue [June 1985]: The Soul of America.

- 1985 – Brian Willan [1984]: Sol Plaatje: A Biography.

- 1982 – John Miller Chernoff [1979]: African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. University of Chicago Press.

- 1981 – Walter Rodney [1972]: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Overture Publications.

- 1980 – James A. Michener [1971]: Kent State: What happened and Why.

- 1980 – Andre Gunder Frank [1966]: The Development of Underdevelopment. Monthly Review Press.

- 1980 – Paul Feyerabend [1975]: Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge.

- 1979 – Aldous Huxley [1945]: The Perennial Philosophy.

- 1978 – Christmas Humphreys [1949]: Zen Buddhism.

- 1977 – Raymond Smullyan [1977]: The Tao is Silent.

- 1976 – Bertrand Russell [1951-1969]: The Autobiography. George Allen & Unwin.

- 1975 – Jean-Francois Revel [1972]: Without Marx or Jesus: The New American Revolution Has Begun.

- 1974 – Charles Reich [1970]: The Greening of America.

- 1973 – Selvarajan Yesudian and Elisabeth Haich [1953]: Yoga and Health. Harper.

- 1972 – Robin Boyd [1960]: The Australian Ugliness.

The Yirrkala Bark Petition

Australia has just commemorated the 50th anniversary of the presentation of the Yirrkala bark panels as a petition to the Australian Commonwealth Parliament in August 1963. The panels are an example of visual art as argument, as I noted here.

Related posts on visual arguments here and here.

Artists concat

Here is a listing of visual artists whose work speaks to me. Minimalists and geometric abstractionists are over-represented, relative to their population in the world. In due course, I will add posts about each of them.

- Carel Fabritius (1622-1654)

- Shi Tao (1641-1720)

- Jin Nong (1687-c.1763)

- Richard Wilson (1714-1782)

- Thomas Jones (1742-1803)

- Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

- Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840)

- John Sell Cotman (1782-1842)

- Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

- Thomas Cole (1801-1848)

- Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–1828)

- Thomas Chambers (1808-1869)

- Thomas Moran (1837-1926)

- Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842-1910)

- Robert Delaunay (1885-1941)

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943)

- Alma Thomas (1891-1978)

- Stuart Davis (1892-1964)

- Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack (1893-1965)

- László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946)

- Kotozuka Eiichi (1906-1979)

- Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

- Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

- Jackson Pollock (1912–1956)

- Gunther Gerzso (1915-2000)

- Michael Kidner (1917-2009)

- Guanzhong Wu (1919–2010)

- Carlos Cruz-Diez (1923- )

- Fred Williams (1927-1982)

- Donald Judd (1928-1994)

- Sol LeWitt (1928-2007)

- Henry Munyaradzi (1931-1998)

- Bridget Riley (1931- )

- Norval Morrisseau (1932–2007)

- Dan Flavin (1933-1996)

- Patrick Tjungurrayi (1935-2018)

- Jean-Pierre Bertrand (1937- )

- Peter Campus (1937- )

- Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980)

- Prince of Wales Midpul (c.1937-2002)

- Peter Struycken (1939- )

- Alighiero e Boetti (1940-1994)

- Alice Nampitjinpa (1943- )

- Helicopter Tjungurrayi (1947- )

- Cildo Meireles (1948- )

- Jeremy Annear (1949- )

- Louise van Terheijden (1954- )

- Doreen Reid Nakamarra (1955-2009)

- Peter Doig (1959- )

- Katie Allen

- Els van ‘t Klooster (1985- )

- Este MacLeod

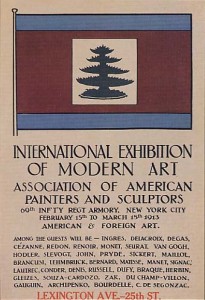

100 years ago at the Armory

It is 100 years since the Armory Show, an influential exhibition of European and American visual art that toured New York, Chicago and Boston. Some 70,000 people attended the New York exhibition (which ran from 1913-02-15 to 1913-03-17), and almost 190,000 the Chicago event. The viewers included former President Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote a review of the show, here. Although not a fan of the cubists and futurists, he was surprisingly open to innovation. An excerpt:

The recent “International Exhibition of Modern Art” in New York was really noteworthy. Messrs. Davies, Kuhn, Gregg, and their fellow members of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors have done a work of very real value in securing such an exhibition of the works of both foreign and native painters and sculptors. Primarily their purpose was to give the public a chance to see what has recently been going on abroad. No similar collection of the works of European “moderns” has ever been exhibited in this country. The exhibitors are quite right as to the need of showing to our people in this manner the art forces which of late have been at work in Europe, forces which cannot be ignored.

This does not mean that I in the least accept the view that these men take of the European extremists whose pictures are here exhibited. It is true, as the champions of these extremists say, that there can be no life without change, no development without change, and that to be afraid of what is different or unfamiliar is to be afraid of life. It is no less true, however, that change may mean death and not life, and retrogression instead of development. Probably we err in treating most of these pictures seriously. It is likely that many of them represent in the painters the astute appreciation of the powers to make folly lucrative which the late P. T. Barnum showed with his faked mermaid. There are thousands of people who will pay small sums to look at a faked mermaid; and now and then one of this kind with enough money will buy a Cubist picture, or a picture of a misshapen nude woman, repellent from every standpoint.

In some ways it is the work of the American painters and sculptors which is of most interest in this collection, and a glance at this work must convince any one of the real good that is coming out of the new movements, fantastic though many of the developments of these new movements are. There was one note entirely absent from the exhibition, and that was the note of the commonplace. There was not a touch of simpering, self-satisfied conventionality anywhere in the exhibition. Any sculptor or painter who had in him something to express and the power of expressing it found the field open to him. He did not have to be afraid because his work was not along ordinary lines. There was no stunting or dwarfing, no requirement that a man whose gift lay in new directions should measure up or down to stereotyped and fossilized standards.”

What with TR’s imperialism and all, it is easy to forget how good a writer he was, being a published author before becoming President. Like another Nobel-Peace-Prize-winning President.

Reference:

Theodore Roosevelt [1913]: A Layman’s Views of an Art Exhibition. Outlook, 103 (29 March 1913): 718–720. Reprinted in Roderick Nash [1970] (Editor): The Call of the Wild (1900–1916). New York: George Braziller.

Transitions 2012

Some who have passed on during 2012 whose life or works have influenced me:

- Graeme Bell (1914-2012), Australian jazz band leader

- Richard Rodney Bennett (1936-2012), British-American musician (heard perform in Canberra in 1976)

- Dave Brubeck (1920-2012), American musician (heard perform in Liverpool in ca. 2003)

- Arthur Chaskalson CJ (1931-2012), South African lawyer and judge

- Heidi Holland (1947-2012), Zimbabwean-South African writer

- Robert Hughes (1938-2012), Australian artist and art critic

- Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012), Brazilian architect

- Bill Thurston (1946-2012), American mathematician

- Ruth Wajnryb (1948-2012), Australian linguist.