Exhibition of abstract expressionist art from the Peggy Guggenheim collection, ING Gallery, Brussels, Belgium.

Archive for the ‘Art’ Category

Page 2 of 7

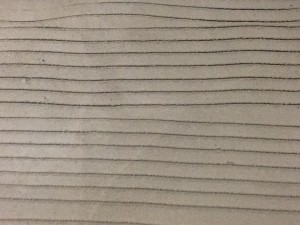

More minimalist art at Temple Station

Following the previous exhibition, described here, more optic minimalism at Temple Underground Station:

Brussels life

Brussels life

Composition xi by Theo van Doesburg at Bozar.

Alice Nampitjinpa at Temple

Workmen replacing the wall tiles at Temple Underground Station in London have temporarily revealed patterns on the concrete walls that bring to mind the sublime optic minimalist art of Alice Nampitjinpa. For a limited time only. Guaranteed to make you homesick for Australia.

Reminded of Nampitjinpa’s Tali at Talaalpi (1998).

London life

Musical Instrument Museums

For reasons of record, here is a list of musical instrument museums, ordered by their location:

- Athens, Greece: Museum of Popular Musical Instruments

- Berlin, Germany: Musikinstrumenten Museum

- Brussels, Belgium: Musical Instrument Museum

- Monte Estoril, Portugal: Museum of Portuguese Music, Casa Verdades de Faria

- New York, NY, USA: Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Phoenix, AZ, USA: Musical Instrument Museum

- Rome, Italy: Museo di Strumenti Musicali dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia

- Vermillion, SD, USA: National Music Museum, University of South Dakota

- Vienna, Austria: Collection of Historic Musical Instruments, Kunsthistorisches Museum

A Minimalist Nativity Scene

A minimalist Nativity scene, by Emilie Voirin:

Mash-up culture

If one trope could define the full diversity of artistic endeavour in this Millenium period, it is the mash-up. For visual art, we have become used to collages of images, videos, fashion, and even material junk. Ditto for sound objects and events. In movies, Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982) became a popular example, at least among college students. And now computer scientists are exploring mashups of programming languages, for instance, here. But not even architecture has escaped. The increasingly widespread Bauhaus-influenced style seen in new office and apartment buildings in Europe and North America these last two decades is one of life’s great pleasures of looking.

What distinguishes this architecture? The influence of Bauhaus and de Stijl ideas is evident in straight edges, flat roofs, vertical walls, and structures comprising rectangular prisms. But these are not the single-box prisms of the International Style skyscrapers of 50 years ago. Rather, each structure comprises multiple, intersecting prisms, expressing a multiplicity of interpenetrating shapes. The result is that external walls are not flat or simply lying in a single vertical plane, but extruding or withdrawing into multiple vertical planes. The effect of this interleaving mash-up is most pleasing.

Second, external surfaces are no longer a single, uniform colour or material. Typically, the different prisms, or the different interpenetrating vertical planes, will be made from different materials: red-brick, white stone or concrete, grey aluminium sheets, etc. Here, the mash-up of materials and colours is unlike most western domestic or office architecture of the past two centuries.

Here are some examples. First is the red-brick apartment building across the street in this photo, in Madison, Wisconsin (Source: via The Dish). Notice how the external walls do not all lie in the same vertical plane, and note the use of different coloured and perhaps even types of surfaces – red-brick, light-coloured brick, and grey slate. There is a white trim.

And here is the Jaclyn Building, in Sofia Bulgaria (Architects: Aedes Studio), again with red brick, grey and white surfaces, but this time less balanced vertically.

And here is an apartment building, The Reach, in Leeds Street, Liverpool, UK, with all the familiar elements along with a curved corner. The only thing lacking from this building is a single tree in green leaf right up against it, to give the image a textured asymmetry of colour and line.

Charles Burney

This post is a history of the family of Charles Burney FRS (1726-1814), musician and musicologist, and his ancestors and descendants.

Sir MacBurney was one of the 60 Knights who participated in a jousting tournament, supervised by Geoffrey Chaucer on the orders of Richard II, held at Smithfield in London in 1390.

One James Macburney is said to have come south to London from Scotland with King James I and VI in 1603. His descendant (likely a grandson), also James Macburney, was born around 1653 and had a house in Whitehall. His son, also called James Macburney (1678-1749), was born in Great Hanwood, Shropshire, around 1678, and attended Westminster School in London. In 1697, he eloped with Rebecca Ellis, against his father’s wishes. As a consequence, the younger James was not left anything when his father died. The younger man’s stepbrother, Joseph Macburney (born of a second wife) was left the entire estate of their father.

This younger James Macburney (1678-1749) was a dancer, violinist and painter, and was supposedly a wit and bon viveur. He and Rebecca Ellis had 15 children over 20 years, of whom 9 survived into adulthood. By 1720, he had moved to Shrewsbury, and Rebecca had died. He married again, to Ann Cooper, who apparently brought money to the union which helped her somewhat feckless husband. This second marriage produced 5 further children, among whom were Richard Burney (1723-1792) (christened “Berney”). The last two children were twins, Charles Burney (1726-1814) and Susanna (1726-1734?), who died at the age of 8. Their father James had apparently dropped the prefix “Mac” around the time of the birth of the twins.

One of Charles’ half-brothers was James Burney (1710-1789), who was organist at St. Mary’s Church, Shrewsbury, for 54 years, from 1732 to 1786. Charles Burney worked as his assistant from 1742 until 1744.

For a period, Charles Burney and his family lived in Isaac Newton’s former house at 35 St Martin’s Street, Leicester Square, London. Among Charles’ children were:

- Esther Burney (1749-1832), harpsichordist, who married her cousin Charles Rousseau Burney (1747-1819), also a keyboardist and violinist.

- Rear Admiral James Burney RN FRS (1750-1821), naval historian and sailor, who twice sailed around the world with Captain James Cook RN.

- Fanny Burney, later Madame d’Arblay (1752-1840), novelist and playwright.

- Rev. Charles Burney FRS (1757-1817), classical scholar.

- Charlotte Ann Burney, later Mrs Broome (1761-1838), novelist.

- Sarah Harriet Burney (1772-1844), novelist.

Charles’ nephew, Edward Francisco Burney (1760-1848), artist and violinist, was a brother to Charles Rousseau Burney, both sons of Richard Burney (1723-1792), Charles’s elder brother. This is a self-portrait of Edward Francisco Burney (Creative Commons License from National Portrait Gallery, London):

In 1793, Fanny Burney married Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste Piochard D’Arblay (1754-1818), an emigre French aristocrat and soldier, and adjutant-general to Lafayette. Their son, Alexander d’Arblay (1794-1837), was a poet and keen chess-player, and was 10th wrangler in the Mathematics Tripos at Cambridge in 1818, where he was a friend of fellow-student Charles Babbage. He was also a member of Babbage’s Analytical Society (forerunner of the Cambridge Philosophical Society), which sought to introduce modern analysis, including Leibnizian notation for the differential calculus, into mathematics teaching at Cambridge. d’Arblay was ordained and served as founding minister of Camden Town Chapel (later the Greek Orthodox All Saints Camden) from 1824-1837, and then served briefly at Ely Chapel in High Holborn, London. The founding organist at Camden Town Chapel was Samuel Wesley (1766-1837).

Not everyone was a fan of clan Burney. Here is William Hazlitt:

“There are whole families who are born classical, and are entered in the heralds’ college of reputation by the right of consanguinity. Literature, like nobility, runs in the blood. There is the Burney family. There is no end of it or its pretensions. It produces wits, scholars, novelists, musicians, artists in ‘numbers numberless.’ The name is alone a passport to the Temple of Fame. Those who bear it are free of Parnassus by birthright. The founder of it was himself an historian and a musician, but more of a courtier and man of the world than either. The secret of his success may perhaps be discovered in the following passage, where, in alluding to three eminent performers on different instruments, he says: ‘These three illustrious personages were introduced at the Emperor’s court,’ etc.; speaking of them as if they were foreign ambassadors or princes of the blood, and thus magnifying himself and his profession. This overshadowing manner carries nearly everything before it, and mystifies a great many. There is nothing like putting the best face upon things, and leaving others to find out the difference. He who could call three musicians ‘personages’ would himself play a personage through life, and succeed in his leading object. Sir Joshua Reynolds, remarking on this passage, said: ‘No one had a greater respect than he had for his profession, but that he should never think of applying to it epithets that were appropriated merely to external rank and distinction.’ Madame d’Arblay, it must be owned, had cleverness enough to stock a whole family, and to set up her cousin-germans, male and female, for wits and virtuosos to the third and fourth generation. The rest have done nothing, that I know of, but keep up the name.” (On the Aristocracy of Letters, 1822).

References:

ODNB

K. S. Grant: ” Charles Burney”, Grove Music Online. (Accessed 2006-12-10.)

POST MOST RECENTLY UPDATED: 2014-08-30.