Thomas Harriott (c. 1560-1621) was an English mathematician, navigator, explorer, linguist, writer, and astronomer. As was the case at that time, he worked in various branches of physics and chemistry, and he was probably the first modern European to learn a native American language. (As far as I have been able to discover, this language was Pamlico (Carolinian Algonquian), a member of the Eastern Algonquian sub-family, now sadly extinct.) He was among those brave sailors and scientists who traversed the Atlantic, in at least one journey in 1585-1586, during the early days of the modern European settlement of North America. Because of his mathematical and navigational skills, he was employed variously by Sir Walter Raleigh and by Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, both of whom were rumoured to have interests in the occult and in the hermetic sciences. Harriott was the first person to use a symbol to represent the less-than relationship (“<“), a feat which may seem trivial, until you realize this was not something that Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Islamic, Indian, or Chinese mathematicians ever did; none of these cultures were slouches, mathematically.

Yesterday, 26 July 2009, was the 400th anniversary of Harriott’s drawing of the moon using a telescope, the first such drawing known. In doing this, he beat Galileo Galilei by a year. The Observer newspaper yesterday honoured him with a brief editorial.

Interestingly, Harriott was born about the same year as the poet Robert Southwell, although I don’t know if they ever met. Southwell spent most of his teenage years and early adulthood abroad, and upon his return to England was either living in hiding or in prison. So a meeting between the two was probably unlikely. But they would have each known of each other.

Previous posts in this series are here. An index to posts about the Matherati is here.

Archive for the ‘Anthropology’ Category

Page 3 of 3

Art as Argument #2

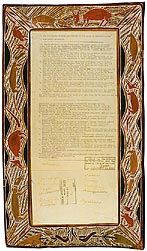

Following my earlier post about the possibility of a work of art being an argument, I want to give another example. This example is also drawn from Australian aboriginal society, and involves a 1997 claim for legal title to land by the Ngurrara people over land in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia. Frustrated by their inability to convince the Native Title Tribunal of their right to the land, the Ngurrara community decided to create a collaborative painting (photographed below) which would demonstrate their traditional rights. The painting was presented, and accepted, as evidence before the Tribunal and is therefore a work of argument, as well as a work of art.

(The Ngurrara Canvas. Painted by Ngurrara artists and claimants, coordinated by Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency, May 1997. 10 metres x 8 metres. Photo: Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency.)

The case is mentioned in a 2003 New Yorker magazine article about aboriginal art by Geraldine Brooks, who says:

“In 1992, the Australian government first recognized the right of Aborigines to claim legal ownership of their ancestral lands – provided they could show evidence of having an enduring connection with them. Before proceeding to court, Aboriginal groups had to make their case before a Native Title Tribunal. Frustrated by their inability to articulate their arguments in courtroom English, the people of Fitzroy Crossing decided to paint their “evidence”. They would set down, on canvas, a document that would show how each person related to a particular area of the Great Sandy Desert – and to the long stories that had been passed down for generations.

“Ngurrara I”, the first attempt, was a canvas that measured sixteen feet by twenty-six feet and was worked on by nineteen artists. It was completed in 1996. But Skipper and Chuguna [two of the artists involved], in particular, didn’t feel that it properly reflected all the important places and stories, so more than forty additional artists were invited to produce a more definitive version. In 1997, “Ngurrara II”, which was twenty-six feet by thirty-two feet, was rolled out before a plenary session of the Native Title Tribunal. It was, one tribunal member said, the most eloquent and overwhelming evidence that had ever been produced there. The Aborigines could proceed to court.” (page 65).

References:

Geraldine Brooks [2003]: “The Painted Desert“, New Yorker, 28 July 2003, pp. 60-67.

Australian National Native Title Tribunal [2002]: Native Title Determination Summary – Marty and Ngurrara. 27 September 2002. Background press release here.

Also, here is a transcript of a radio story (broadcast 1997-07-15) on Australian ABC radio about the submission of the painting as evidence to the Native Title Tribunal.

More on different forms of geographic knowledge here.

Art as argument

Can a work of visual art be an argument? I believe the answer to this question is yes. In this and in some future posts, I will give examples, drawn from Australian Aboriginal art and from pure mathematics.

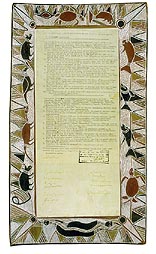

In August 1963, the Yolgnu people of Yirrkala (eastern Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory) petitioned the Australian Government for legal rights to traditional land. The petition was in the form of two painted bark panels. The argument for land rights was made in three ways — in English text, in Gumatj text, and in the surrounding art, which depicted the traditional relations between the Yolgnu people and their land. It is important to note that the visual images are not mere decoration of the text, but a presentation of the same argument in a different language, a visual language.

The artwork of the Yolngu Bark Petition (copied above) is a form of argument, for a claim asserting traditional rights to particular land. The reason that the artwork is an argument derives from the general nature of traditional Australian Aboriginal art, which presents a diagrammatic or iconic description of a particular geographic region, identifying the landscape features of that region (eg, rivers, hills, etc) along with the dreamtime entities (animals, trees, spirits) who are believed to have created the region and may still inhabit it. (The “dreamtime” is the period of the earth’s creation.) The art derives from stories of creation for the region, which are believed to have been handed down (orally and via artwork) to the current inhabitants from the original dreamtime spirits through all the intermediate generations of inhabitants.

Accordingly, the only people who have the necessary knowledge, and the necessary moral right, to create an artistic depiction of a region are those who have been the recipients of that region’s creation story. In other words, the fact that the Yolngu people were able to draw this depiction of their region is itself evidence of their long-standing relationship to the specific land in question. The existence of the art-work depicting the local landscape is thus an argument for their claim to ownership rights to that land. (Note that the art work’s role as argument arises primarily from the special nature of the claim it supports; the art is not, and could not easily be, an argument for any other kind of claim.)

In support of this position, I present some quotations, the first several as explanation for people unfamiliar with Australian aboriginal mythology and art.

Judith Ryan (1993, p. 50):

The term “Dreaming” is difficult for us to comprehend because of its use as noun and adjective in imprecise and ungrammatical ways to refer to the creation period, conception site, totem, Ancestral being, ground of existence, and the notions of supernatural, eternal or uncreated.”

Jean-Hubert Martin (1993, p. 32):

One can more or less imagine what “Dreaming” is: that link between the individual and his land, between the clan and its territory. The paintings [of Aboriginal artists] show figured spaces representing spaces both physical and mental, but it is difficult to go much further than that.

Following Aboriginal explanations one can recognise and name the various elements in these paintings. The thought structure, the references and the signifance of these words and fragments of speech – which reach us distorted by translation – still remain an enigma despite the valiant attempt to explain them in the ensuing texts. A not inconsiderable difficulty is posed by the mystery surrounding certain rituals and their formal depiction. And, one has to remember that what we see today of Aboriginal art is only that which we have been allowed to see.”

Ulrich Krempel (1993, p. 38) quotes C. Anderson/F. Dussart (1988, p. 18), as follows:

When asked about their paintings, [Australian Aboriginal] artists usually respond that the painting “means” or is “my country”, that is, it is a depiction of the painter’s territory. When queried further about the “Dreaming” story, the artist will often identify the main Ancestor depicted and perhaps the primary site at which the Ancestor undertook the actions portrayed in the painting. It is possible for an outsider, especially if working in the local language, to gain further insight into the narrative of events described in the painting, but even then access to the different levels of meaning may be restricted.”

Three quotations from Horward Morphy [1991]:

From a Yolngu perspective, paintings are not so much a means of representing the ancestral past as one dimension of the ancestral past . . .” (page 292)

Yolngu art also provides a framework for ordering the relations between people, ancestors, and land.” (page 293)

Paintings [in Yolngu society] gain value and power through their incorporation in such a process [of cultural definition], through being integral to the way a system (of clan-based gerontocracy) is reproduced, and through being part of its ideological support. Paintings gain power because they are controlled by powerful individuals, because they are used to discriminate between different areas of owned land, because they are used to mark status, to separate the initiated from the uninitiated and men from women. Their use in sociopolitical contexts creates part of their value. However, their value is also conceptualized in other terms, in terms of their intrinsic properties.” (page 293)

Janien Schwarz (1999, pp. 56-57):

In the first section, I argue that an understanding of the Bark Petitions is inseparable from an understanding of Yolngu relations to land. In Yolngu culture, the painting of designs is regarded as constructing an interface between the ground, its spiritual essence, and specific groups of people. The designs on the Petition are inseparable from these associations, in particular from the geographic locations at which they originated during Creation or wangarr. Putting the Petitions’ clan designs in a Yolngu cultural context reveals their strong artistic and political links to the Yolngu people and their land. With mounting pressures on land use from outsiders, Yolngu people have disclosed their designs (and inferred connections to land) through the context of art and art exhibitions as a political means of laying claim to their country which is under threat by bauxite mining. I present the Petitions as part of a larger history of Aboriginal people negotiating for land rights and cultural recognition through the production and presentation of painted barks and other objects of spiritual significance. . . . I contend that the painted motifs on the Bark Petitions merit interpretation as land claims and that, by extension, the paintings are a form of petition.”

References:

C. Anderson/F. Dussart: “Dreamings in Acrylic: Western Desert Art”. Catalog for Exhibition: Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. P. Sutton, Editor. Ringwood, Melbourne, 1988. p. 118.

Ulrich Krempel [1993]: “How does one read “Different” Pictures? Our encounter with the aesthetic product of other cultures”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 37-40.

Bernhard Luthi and Gary Lee (Editors) [1993]: Aratjara: Art of the First Australians. Exhibition Catalog. Dusseldorf, Germany: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Jean-Hubert Martin [1993]: “A Delayed Communication”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 32-35.

Horward Morphy [1991]: Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Judith Ryan [1993]: “Australian Aboriginal Art: Otherness or Affinity?”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 49-63.

Janien Schwarz [1999]: Beyond Familiar Territory: Dissertation: Decentering the Centre. An analysis of visual strategies in the art of Robert Smithson, Alfredo Jaar and the Bark Petitions of Yirrkala; and Studio Report: A Sculptural Response to Mapping, Mining, and Consumption. PhD Thesis, Canberra School of Art, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Available from here.

Language and thought

A very interesting essay by Lera Boroditsky on the relationship between language and thought. Comparing languages and cognitive styles in different cultures, she concludes that the structure of a language may influence what we most attend to, and thus our modes of thinking. (HT: AS)

Follow me to Pormpuraaw, a small Aboriginal community on the western edge of Cape York, in northern Australia. I came here because of the way the locals, the Kuuk Thaayorre, talk about space. Instead of words like “right,” “left,” “forward,” and “back,” which, as commonly used in English, define space relative to an observer, the Kuuk Thaayorre, like many other Aboriginal groups, use cardinal-direction terms — north, south, east, and west — to define space. This is done at all scales, which means you have to say things like “There’s an ant on your southeast leg” or “Move the cup to the north northwest a little bit.” One obvious consequence of speaking such a language is that you have to stay oriented at all times, or else you cannot speak properly. The normal greeting in Kuuk Thaayorre is “Where are you going?” and the answer should be something like ” Southsoutheast, in the middle distance.” If you don’t know which way you’re facing, you can’t even get past “Hello.”

The result is a profound difference in navigational ability and spatial knowledge between speakers of languages that rely primarily on absolute reference frames (like Kuuk Thaayorre) and languages that rely on relative reference frames (like English). Simply put, speakers of languages like Kuuk Thaayorre are much better than English speakers at staying oriented and keeping track of where they are, even in unfamiliar landscapes or inside unfamiliar buildings. What enables them — in fact, forces them — to do this is their language. Having their attention trained in this way equips them to perform navigational feats once thought beyond human capabilities. Because space is such a fundamental domain of thought, differences in how people think about space don’t end there. People rely on their spatial knowledge to build other, more complex, more abstract representations. Representations of such things as time, number, musical pitch, kinship relations, morality, and emotions have been shown to depend on how we think about space. So if the Kuuk Thaayorre think differently about space, do they also think differently about other things, like time? This is what my collaborator Alice Gaby and I came to Pormpuraaw to find out.

To test this idea, we gave people sets of pictures that showed some kind of temporal progression (e.g., pictures of a man aging, or a crocodile growing, or a banana being eaten). Their job was to arrange the shuffled photos on the ground to show the correct temporal order. We tested each person in two separate sittings, each time facing in a different cardinal direction. If you ask English speakers to do this, they’ll arrange the cards so that time proceeds from left to right. Hebrew speakers will tend to lay out the cards from right to left, showing that writing direction in a language plays a role. So what about folks like the Kuuk Thaayorre, who don’t use words like “left” and “right”? What will they do?

The Kuuk Thaayorre did not arrange the cards more often from left to right than from right to left, nor more toward or away from the body. But their arrangements were not random: there was a pattern, just a different one from that of English speakers. Instead of arranging time from left to right, they arranged it from east to west. That is, when they were seated facing south, the cards went left to right. When they faced north, the cards went from right to left. When they faced east, the cards came toward the body and so on. This was true even though we never told any of our subjects which direction they faced. The Kuuk Thaayorre not only knew that already (usually much better than I did), but they also spontaneously used this spatial orientation to construct their representations of time.

People’s ideas of time differ across languages in other ways. For example, English speakers tend to talk about time using horizontal spatial metaphors (e.g., “The best is ahead of us,” “The worst is behind us”), whereas Mandarin speakers have a vertical metaphor for time (e.g., the next month is the “down month” and the last month is the “up month”). Mandarin speakers talk about time vertically more often than English speakers do, so do Mandarin speakers think about time vertically more often than English speakers do? Imagine this simple experiment. I stand next to you, point to a spot in space directly in front of you, and tell you, “This spot, here, is today. Where would you put yesterday? And where would you put tomorrow?” When English speakers are asked to do this, they nearly always point horizontally. But Mandarin speakers often point vertically, about seven or eight times more often than do English speakers.

POSTSCRIPT (ADDED 2010-08-29): An article by Guy Desutscher in the NYT covering similar ground is here.

Why vote?

Someone once joked that economists are people who see something working in practice, and then wonder if it will also work in theory. One practice that mainstream economists have long failed to explain theoretically is voting. Following the (so-called) rational choice models of Arrow and Downs, they calculate the likely net monetary benefit of voting to an individual voter, and compare that to the likely net costs to the voter. With long queues due to inadequately-resourced or incompetently-managed voting administrations (such as those in many US states), these costs can be considerable. Since one vote is very unlikely to have any marginal consequences, economists are stumped as to why any person votes.

One explanation for voting, of course, is that voters are indeed feeble-minded or irrational, unable to calculate the costs and benefits themselves, or, if they can, unable to act in their own self-interest. This is the standard explanation, and it strikes me as morally reprehensible: a failure to explain or model some phenomenon theoretically is justified on the grounds that the phenomenon should not exist.

Another explanation for voting may be that the rational-choice models understate the benefits or overstate the costs to individuals of voting. Some economists, as if in a parody of themselves, have now – in 2008! – discovered altruism. Factor in the benefits to others, this study claims, and the balance of benefits to costs may move more in favour of benefits.

A third explanation for voting may be that rational-choice models are simply inappropriate to the phenomena under study. The rational choice model assumes that citizens in a democracy are passive consumers of political ideas and proposals, with their only action being the selection of representatives at election times. Since at least the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, this quaint notion of a passive citizenry has been rebutted repeatedly by direct political action by citizens. The most famous example, of course, was the uprising against colonial taxation known as the American War of Independence, which, one imagines, some economist or two may have heard speak of. There’s also the various revolutions and uprisings of 1789, 1791, 1848, 1854, 1871, 1905, 1910, 1917, 1926, 1949, 1953, 1956, 1968 and 1989, just to list the most important since economics began to be studied systematically.

An historically-informed observer would surely conclude that a model of voting in which citizens produce as well as consume political ideas is likely to have more calibrative traction than one in which citizens do nothing except (if they so choose) vote. Such a theory already exists in political science, where it goes under the name of deliberative democracy. One wonders what terrors would strike the earth were an economist to read the relevant literature before modeling some domain.

People vote not only out of their own self-interest (if they ever do that), but also to influence the direction of their country, to act in solidarity with others, to elect to join a group, to demonstrate membership of a group, to respond to peer pressure, because the law requires they do, or to exercise a hard-won civil right. Only a person with no sense of history – an economist, say – would fail to understand the importance – indeed, the extreme rationality – of this last factor, especially during a year when a major political party has nominated a black candidate for President of the USA, and the other party a woman for Veep. At the founding of the USA, neither candidate would have been allowed to vote.

Not for the first time, mainstream economics has ignored social structures and processes when studying social phenomena, focusing only on those factors which can be assigned to an individual (indeed, some idealized, self-interested, desiccated calculating machine) and, within these, only on factors able to be quantified. The big question here is not why people vote, which is obvious, but why economists seem unable to recognize social structures and processes which can be clearly seen by most everyone else. What is it about mainstream economists that makes them autistic in this regard? Do they simply have an under-supply of inter-personal intelligence, unable to empathize with or reason about others?

References and Acknowledgments:

Hat-tip to Normblog.

Kenneth J. Arrow [1951]: Social Choice and Individual Values. New York City, NY, USA: Wiley.

J. Bessette [1980]: “Deliberative Democracy: The majority principle in republican government”, pp. 102-116, in: R. A. Goldwin and W. A. Schambra (Editors): How Democratic is the Constitution? Washington, DC, USA: American Enterprise Institute.

James Bohman and William Rehg (Editors) [1997]: Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Anthony Downs [1957]: An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York City, NY, USA: Harper and Row.

Viral marketing

The International Herald Tribune carried an article about viral marketing and counter-viral marketing in US Presidential races last week. The attackers and defenders have been at this game for a couple of centuries, only the technologies have changed.

Complexity of communications

Recently, I posted about probability theory, and mentioned its modern founder, Andrei Kolmogorov. In addition to formalizing probability theory, Kolmogorov also defined an influential approach to assessing the complexity of something.

He reasoned that a more complex object should be harder to create or to re-create than a simpler object, and so you could “measure” the degree of complexity of an object by looking at the simplest computer program needed to generate it. Thus, in the most famous example used by complexity scientists, the 1915 painting called “Black Square” of Kazimir Malevich, is allegedly very simple, since we could recreate it with a very simply computer program:

Paint the colour black on every pixel until the surface is covered, say.

But Kolmogorov’s approach ignores entirely the context of the actions needed to create the object. Just because an action is simple or easily described, does not make it easy to do, or even easy to decide to do. Art objects, like most human artefacts, are created with deliberate intent by specific creators, as anthropologist Alfred Gell argued in his theory of art. To understand a work of art (or indeed any human artefact) we need to assess its effects on the audience in the light of its creator’s intended effects, which means we need to consider the intentions, explicit or implicit, of its creators. To understand these intentions in turn requires us to consider the context of its creation, what a philosopher of language might call its felicity conditions.

Malevich’s Black Sqare can’t be understood, in any sense, without understanding why no artist before him created such a painting. There is no physical or technical reason that Rembrandt, say, or Turner, could not have painted a canvas consisting only of one colour, black. But they did not, and could not have, and could not even have imagined doing so. (Perhaps only the 18th-century Welsh painter Thomas Jones could have imagined doing so, with his subtle paintings of near-monochrome Neapolitan walls.) It is not a coincidence that Malevich’s painting appeared in the historical moment when it did, and not anytime before nor anyplace else. For instance, Malevich worked at a time when educated people were fascinated with notions of a fourth or even further dimensions, and Malevich himself actively tried to represent these other dimensions in his art. To imagine that such a painting could be adequately described without reference to any art-historical background, or socio-political context, or the history of ideas is to confuse the syntax of the painting with its semantics and pragmatics. We understand nothing about the painting if all we understand is that every pixel is colored black.

We have been here before. The mathematical theory of communications of Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver has been very influential in the design of the physical layers of telecommunications and computer communications networks. But this theory explicitly ignores the semantics – the meanings – of messages. (To be fair to Shannon and Weaver they do tell us explicitly early on that they will be ignoring the semantics of messages.) Their theory is therefore of no use to anyone interested in communications at layers above the physical transmission of signals, that is, anyone interested in understanding or using communication to communicate with other people or machines.

References:

M. Dabrowski [1992]: “Malevich and Mondrian: nonobjective form as the expression of the “absolute”. ” pp. 145-168, in: G. H. Roman and V. H. Marquardt (Editors): The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910-1930. Gainesville, FL, USA: University Press of Florida.

Alfred Gell [1998]: Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

L. D. Henderson [1983]: The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

Claude E. Shannon and Warren Weaver [1963]: The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Illinois Press.

How to manage creatives (not)

Managing creative talent is always difficult, but locking artists in battery farms seems somewhat extreme.

Nominal imperialism at IKEA

Apparently, Swedish furniture retailer IKEA has systematically applied Danish names to doormats and carpets, while keeping Swedish names for more expensive items of furniture. If this pattern of naming is systematic as claimed, then it is hard to see how it could be accidental or inadvertant. If the pattern was accidental, we should expect IKEA to issue a hasty apology for any unintended offence caused, to Danes or to others. Instead, IKEA went on the offensive, with a spokesperson allegedly saying:

“these critics appear to greatly underestimate the importance of floor coverings. They are fundamental elements of furnishing. We draw worldwide attention to Danish place names with our products.”

Whatever the perceived justification, insulting your customers can never be great marketing. One of the features of colonialism is a lack of appreciation for the feelings of the colonized. Hundreds of years of condescension are manifest in those three sentences. Danes have every right to be offended.

UPDATE (2008-03-17): Spiegel Online have now retracted their original news story (the retraction is at the same address as was the article), although it is not clear from this retraction that either the original allegation against IKEA or the quoted response from an IKEA spokesperson are inaccurate. Here is the text of the retraction of the news story by Spiegel Online:

03/06/2008

Retraction

‘Is IKEA Giving Danes the Doormat Treatment?’

In the article originally published at this address, SPIEGEL falsely reported that Danish researchers Klaus Kjøller and Trøls Mylenberg had conducted a “thorough analysis” of the naming conventions at Swedish furniture maker IKEA. In fact, Kjøller was approached by a journalist from the free daily Nyhedsavisen who had inquired about why apparently inferior IKEA products had been given the names of Danish towns.Kjøller answered the question, but says he was very surprised by the “extremely exaggerated” article that appeared on the cover of Nyhedsavisen the following day, which would later get picked up by other media in Denmark and abroad, including SPIEGEL ONLINE.

“The story sounds good, but it unfortunately isn’t true,” Kjøller told SPIEGEL ONLINE on Monday. The author of the article and the editorial staff failed to contact Kjøller prior to the publication of the article.

SPIEGEL ONLINE strives to adhere to the highest standards of reporting and apologizes to its readers for the error, which we deeply regret.

— The Editors

UPDATE 2 (2012-09-14): Yet, it seems, IKEA does indeed have a naming policy in which different categories of products are given names from a particular category of real-world places and objects. Finnish place names are used for dining furniture, for instance. In this schematic, it seems that carpets are assigned Danish place names. This is certainly not inadvertent, but deliberate. Why were these products assigned those particular names?