I am belatedly posting about a superb address I heard given at a mass to celebrate the Fourth Centenary of the (then) English Province of the Society of Jesus, held in Farm Street Church, London on 21 January 2023. The mass was celebrated by Vincent Cardinal Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster, and the sermon given by Fr Damian Howard SJ, Provincial of the British Province. The music at the mass included the world premiere of James MacMillan’s “Precious in the sight of the Lord” (with MacMillan in the congregation).

Search Results for ‘southwell’

Page 0 of 2

An eternal golden braid

These are the people I will invite to the first annual party to celebrate the availability of cost-effective time travel:

Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464)

Matteo Ricci SJ (1552-1610)

Thomas Harriott (1560-1621)

Robert Southwell SJ (c.1561-1595)

Kit Marlowe (1564-1593)

Henry Wriothesley (1573-1624)

Charles Diodati (c.1608-1638)

Shi Tao (1641-1720)

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753)

Johann Baptist Vanhal (1739-1813)

Edward Francisco Burney (1760-1848)

Alexander d’Arblay (1794-1837)

Eduard Rietz (1802-1832)

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875)

Juan Crisóstomo Jacobo Antonio de Arriaga y Balzola (1806-1826)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Arthur Hallam (1811-1833)

Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (1820-1894)

Henry Horton McBurney (1843-1875)

Marian “Clover” Hooper Adams (1843-1885)

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904)

Wolcott Balestier (1861-1891)

Warwick Potter (1870-1893)

Joseph Trumbull Stickney (1874-1904)

Jan Letzel (1880-1925)

David Kammerer (1911-1944)

John Medill McCormick (1916-1938)

Lucien Carr (1925-2005)

Christophe Bertrand (1981-2010)

Our life is but lent

“Our life is but lent; a good whereof to make, during the loan, our best commodity. It is a debt due to a more certain owner than ourselves, and therefore so long as we have it, we receive a benefit; when we are deprived of it, we suffer no wrong. We are tenants at will of this clayey farm, not for any term of years; when we are warned out, we must be ready to remove, having no other title but the owner’s pleasure. It is but an inn, not a home; we came but to bait, not to dwell; and the condition of our entrance was finally to depart. If this departure be grievous, it is also common; this today to me, tomorrow to thee; and the case equally affecting all, leaves none any cause to complain of injurious usage.”

Robert Southwell SJ: The Triumphs over Death.

Memory

We keep books because they are personal souvenirs of the past – physical reminders of the feelings we had while reading them. The same goes for concert programs and tickets for sporting events, which many people keep. As more of our life goes online, we risk losing such souvenirs. Only the online record itself may provide a long-term reminder of something, or someone.

On the other hand, the web makes it vastly easier to bring to wide attention something or someone who should be remembered. In the early days of photography, photographers recorded memorable events, such as weddings and Presidential inaugurations. Susan Sontag noticed that something changed as photography ceased to be only done by professionals and became a democratic pastime: the relationship between events and photographs switched. Now events were memorable (and remembered) precisely because they had been photographed. The web is effecting the same reversal, I believe.

I can record a person of great influence on my life, who would otherwise be entirely forgotten to history, or people whom I never met, but whose words and actions have affected mine, for example, the activist-poets Vadim Delone, or Robert Southwell. I can record people who think differently to the verbal paradigm which so dominates contemporary western culture – the matherati, say, or musical thinkers. I can even use the Web to find and trace the genealogy of some of my own musical thinking, say, and then record for posterity these cross-generational networks of connections. Since so much of written history is by definition written by people au fait with language-based thought, it is particularly important that minority, non-language thinkers are not forgotten. (Many more people know, for instance, of the writers of Japanese haiku poetry in the Edo period than do of the ordinary people who solved temple geometry problems, the Sangaku.)

The souvenirs I mention above are mostly personal, perhaps of little interest to anyone else. The same became true of photographs, early in their adoption. The Web also lets us record for posterity events and people of much wider significance. Perhaps the best recent example I know is Normblog’s admirable and riveting series of Holocaust stories, Figures from a Dark Time. Apparently not everyone agrees that this series is worth doing. Let me add my strong opinion that this recording is both necessary and important, and we should all be very grateful for Norm’s efforts. After 9/11, the New York Times published short obituaries of every person killed in the attack. Although it may be too late, we should be aiming for the same in remembering the Holocaust.

Most-viewed posts

The top 21 most-viewed posts on this blog, since its inception (in descending order):

- Australian political language

- Poem: Song (by Joe Stickney)

- Art: Katie Allen at Mostyn Gallery, Llandudno

- Complexity of communications

- Knowing and understanding The Other

- Obama’s eloquence central to ability to govern

- The birds

- At the hot gates: a salute to Nate Fick

- Hearing is (not necessarily) believing

- The long after-life of design decisions

- Manhattanhenge

- The strange disappearance of British manufacturing

- Nicolas Fatio de Duillier

- Contemporary Chinese ceramics: Liu JianHua

- The Mathematical Tripos at Cambridge

- Vale, Studs Terkel

- Firebird in Bologna

- A data architecture for spimes

- Poem: Times go by Turns (by Robert Southwell)

- Mr Sculthorpe, please call your office

- Berger on drawing

(Photo of Paul Keating, credit: AFR).

East of my day's circle

I have written before about Robert Southwell SJ, poet, martyr and Shakespeare’s cousin, and quoted some of his poems. Southwell (c. 1561-1595) was an English Jesuit from an aristocratic family, whose mother had been a governess and friend of Queen Elizabeth I. He left England illegally to study for the priesthood and returned — again illegally — to live and minister in secret to England’s oppressed Catholic population. He was captured, tortured by Elizabeth’s sadistic religious police, subjected to a show trial, and publicly executed.

Southwell was a poet of fine sensitivity, and drew on his Jesuit spiritual training to become the first English poet to develop personation (or subjectivity), a psychologically-real description of the interior self. His cousin Will Shakespeare was to adopt this idea in his poetry and plays, so that (for example) we learn about Hamlet’s internal mental deliberations, not only about his public actions and conversations. The late Anne Sweeney argued that Southwell developed personation in his poetry as a direct result of completing the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Lopez of Loyala, a process of meditation and self-reflection which all Jesuits undertake. In her words (p. 80):

The core experience of the Ignatian Exercises was the reading and learning of the hidden self, the exercisant learning to define his reponses according to a Christian morality that would then moderate his behaviour. After a powerfully imagined involvement in, say, Christ’s birth, he was required to withdraw the mind’s eye from the scene before him and redirect it into himself to analyse with care the feelings thereby aroused.”

It would be interesting to know if Ignatius himself drew on literary models from (eg) Basque, Catalan or Spanish in devising the Exercises.

Living underground and on the run, Southwell wrote poetry for a community unable to obtain prayer books or to easily hear preachers; poetry was thus a substitute for sermons and for personal spiritual counselling, and a form of prayer and spiritual meditation. His poetry is also strongly visual.

Because the Jesuit mission to England during Elizabeth’s reign was forced underground it is not surprising that Jesuit priests mostly lived in the homes of rich or noble Catholics, or Catholic sympathizers, sometimes hidden in secret chambers. It is more surprising that there were still English nobles willing to risk everything (their wealth, their titles, their freedom, their homeland, their lives) to hide these priests. One such family was that of Philip Howard, the 20th Earl of Arundel (1557-1595), who was 10 years a prisoner of Elizabeth I, refusing to recant Catholicism, and who died in prison without ever meeting his own son. Howard’s wife, Anne Dacre (1557-1630), was also a staunch Catholic. The earldom of Arundel is the oldest extant earldom in the English peerage, dating from 1138.

The Howard’s London house on the Thames was one of the noble houses which sheltered Robert Southwell for several years. The location of their home, between the present-day Australian High Commission and Temple Tube station, is commemorated in the names of streets and buildings in the area: Arundel Street, Surrey Street, Maltravers Street (all names associated with the Arundel family), Arundel House, Arundel Great Court Building, the former Swissotel Howard Hotel, and the former Norfolk Hotel (now the Norfolk Building in King’s College London) in Surrey Street. Maltravers Street is currently the location for a nightly mobile soup kitchen. Of course, in Elizabethan times the Thames was wider here, the Embankment only being built in the 19th century. One can still find steps in some of the side streets leading to the Thames descending at the edge where the previous riverbank used to be, for instance on Milford Lane.

Southwell also, it seems, spent time in the London house of his cousin Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624), who was also Shakespeare’s patron and cousin. Southampton’s house then was a short walk away, in modern-day Chancery Lane, on the east side of Lincoln’s Inn fields. Southampton was part of the rebellion of Robert Deveraux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1565-1601) against Elizabeth in February 1601. The London house of Essex was also along the Thames, downstream and adjacent to that of the Howard family. The street names there also recall this history: Essex Street, Devereaux Court.

Supporters of Essex, chiefly brothers of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland (1564-1632), paid for a performance of Shakespeare’s play, Richard II, the evening before the rebellion. Percy was married to Dorothy Devereaux (1564-1619), sister of Robert, and was regarded as a Catholic sympathizer. Percy also employed Thomas Harriott (1560-1621), a member of the matherati. Given the physical proximity of these noble villas, it is likely too that Southwell and Harriott met and knew each other.

And, weirdly, Essex and Norfolk are adjacent streets in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, too (close by and parallel to Orchard Street).

References:

The image is Shown a plan of Arundel House, the London home of the Earls of Arundel, as it was in 1792 (from the British Library). The church shown in the upper right corner is St. Clement Danes, now the home church of the Royal Air Force.

Christopher Devlin [1956]: The Life of Robert Southwell: Poet and Martyr. New York, NY, USA: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.

Robert Southwell [2007]: Collected Poems. Edited by Peter Davidson and Anne Sweeney. Manchester, UK: Fyfield Books.

Anne R. Sweeney [2006]: Robert Southwell: Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape 1586-1595. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Shakespeare's cousins

I have remarked before that whoever wrote William Shakespeare’s plays and poetry was deeply familiar with the poetry and prose of Robert Southwell SJ, and had access to Southwell’s works in manuscript form. We know this because most of Southwell’s output was only published after his execution in 1595, and Shakespeare’s poetry shows Southwell’s influence well before this date.

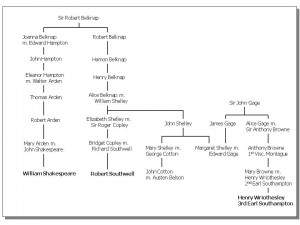

Shakespeare and Southwell were cousins, and both were also cousins to Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron and the likely dedicatee of the Sonnets. John Klause, in his fine book tracing the influence of Southwell’s writing on Shakespeare’s own words, includes a family tree showing the family connections between these three Elizabethans. I reproduce some of the tree below, copied from page 40 of Klause’s book. Southwell’s mother, Bridget Copley, was a governess to the young Princess Elizabeth, so the connections to the royal family were close. In addition, Southwell and Shakespeare were also connected through the Vaux and Throckmorton families (Devlin has another family tree, page 264).

And the family connection between Southwell and Wriothesley was in fact closer than Klause’s tree indicates. Southwell’s eldest brother Richard married Alice Cornwallis, a niece of Henry Wriothesley senior, second Earl of Southampton and the third Earl’s father, and Southwell’s eldest sister Elizabeth married a nephew of the same second earl, a son of Margaret Wriothesley and Michael Lister. Thus, Robert Southwell was twice a second cousin by marriage to Henry Wriothesley junior, third Earl (Devlin tree, p. 15).

References:

Christopher Devlin [1956]: The Life of Robert Southwell: Poet and Martyr. New York, NY, USA: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.

John Klause [2008]: Shakespeare, the Earl, and the Jesuit. Teaneck, NJ, USA: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Writing Shakespeare

Since the verified facts of Shakespeare’s life are so few, even a person normally skeptical of conspiracy theories could well consider it possible that the plays and poetry bearing the name of William Shakespeare were written by A. N. Other. But just who could have been that other?

Well, even with few verified facts about Shakespeare’s life, we can know some facts about the author of these texts by reading the texts themselves. Whoever was the author must have spent a lot of time hanging about with actors, since knowledge of, and in-jokes about, acting and the theatre permeate the plays. Also, whoever it was must have grown up in a rural district, not in a big city, since the author of the plays and the poetry knows a great deal about animals and plants, about rural life and its myths and customs, and rural pursuits. Whoever it was also had close connections to Warwickshire, since the plays contain words specific to that area.

Also, whoever it was must have had close personal or family connections to the old religion (Catholicism), since many of the plays make detailed reference to, or indeed seem to be allegories of, the religious differences of the time (Wilson 2004, Asquith 2005). Whoever it was was close enough to the English court to write plays which discussed current political issues using historically-relevant allegories, yet not so close that these plays themselves or their performances (with just one exception) were seen as interventions in court intrigues.

Whoever it was also knew well the samizdat poetry of Robert Southwell, poet and Jesuit martyr, since some of the poetry and plays respond directly to Southwell’s poetry and prose (Wilson 2004, Klause 2008). To have responded to Southwell’s writing before 1595, as the writer of Shakespeare’s narrative poems and early plays did, required access to Southwell’s unpublished, illegal, dissident manuscripts. Southwell and Shakespeare were cousins (Klause 2008 has a family tree).

And finally whoever it was was not a playwright or poet already known to us, since these texts differ stylistically from all other written work of the period, while exhibiting strong stylistic similarity among themselves.

There is only one candidate who fits all these criteria, and his name is William Shakespeare. Anyone seriously proposing an alternative to Shakespeare as the author of Shakespeare’s plays and poetry needs to explain how that person could have written poetry and plays with all the features described above. Every alternative theory so far advanced – Kit Marlowe, the Earl of Oxford, Francis Bacon, Elizabeth I, et al. – falls at the factual hurdles created by the texts themselves.

Note: Klause [2008, p. 40] presents a genealogy which shows that Robert Southwell and William Shakespeare shared a great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Sir Robert Belknap (c. 1330-1401, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas of England, 1377-1388) – Southwell through his mother, Bridget Copley, and Shakespeare through his mother, Mary Arden. In addition, the great-great-grandfather, Sir John Gage, of Shakespeare’s patron, Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, was also grandfather to Edward Gage, husband of Margaret Shelley, Southwell’s mother’s first cousin and, like his mother, a descendant of Sir Robert Belknap. In the extended families of Elizabethan society, all three – Shakespeare, Southwell and Wriothesley – would have been seen as, and would have known each other as, cousins. The bonds across such extended family relationships were strong. Having lived in contemporary societies (in Southern Africa) where extended families still play a prominent role (Bourdillon 1976), the strong loyalty and close brotherhood engendered across such apparently-distant connections is perfectly understandable to me, if not yet to all Shakespeare scholars.

References:

Clare Asquith [2005]: Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. UK: Public Affairs.

Michael F. Bourdillon [1976]: The Shona Peoples: An Ethnography of the Contemporary Shona, with Special Reference to their Religion. Shona Heritage Series. Gwelo, Rhodesia (now Gweru, Zimbabwe): Mambo Press.

John Klause [2008]: Shakespeare, the Earl and the Jesuit. Madison, NJ, USA: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Anne R. Sweeney [2006]: Robert Southwell: Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape 1586-1595. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Richard Wilson [2004]: Secret Shakespeare: Studies in Theatre, Religion and Resistance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Poem: Joseph's Amazement

Following Michael Dransfield’s poem about conflicted love, I remembered a seasonally-appropriate poem written four centuries before: Robert Southwell’s Joseph’s Amazement, which imagines the torment and self-questioning Mary’s husband would have felt to discover that Mary was pregnant. Southwell moves between first and third persons to describe Joseph’s anguish, which he does not resolve, instead ending in a similar place of uncertain quandary to Dransfield. Perhaps this lack of resolution is another reason Southwell’s poetry sounds so modern, and so fresh.

Joseph’s Amazement

When Christ, by growth, disclosed his descent

Into the pure receipt of Mary’s breast

Poor Joseph, stranger yet to God’s intent,

With doubts of jealous thoughts was sore oppressed

And, wrought with diverse fits of fear and love,

He neither can her free nor faulty prove.

Now sense, the wakeful spy of jealous mind,

By strong conjectures deemeth her defiled,

But love, in doom of things best loved blind,

Thinks rather sense deceived than her with child

Yet proofs so pregnant were that no pretence

Could cloak a thing so dear and plain to sense.

Then Joseph, daunted with a deadly wound,

Let loose the reins to undeserved grief.

His heart did throb, his eyes in tears were drowned,

His life a loss, death seemed his best relief.

The pleasing relish of his former love

In gallish thoughts to bitter taste doth prove.

One foot he often setteth forth of door

But t’other’s loath uncertain ways to tread.

He takes his fardel for his needful store,

He casts his Inn where first he means to bed.

But still ere he can frame his feet to go,

Love winneth time till all conclude in no.

Sometime, grief adding force, he doth depart.

He will, against his will, keep on his pace.

But straight remorse so racks his ruing heart,

That hasting thoughts yield to a pausing space;

Then mighty reasons press him to remain.

She whom he flies doth win him home again.

But when his thought, by sight of his abode,

Presents the sign of mis-esteemed shame,

Repenting every step that back he trod,

Tears drown the guides; the tongue, the feet doth blame.

Thus warring with himself a field he fights,

Where every wound upon the giver lights.

“And was my love,” quoth he, “so lightly prized?

Or was our sacred league so soon forgot?

Could vows be void, could virtues be despised?

Could such a spouse be stained with such a spot?”

O wretched Joseph that hast lived so long,

Of faithful love to reap so grievous wrong.

Could such a worm breed in so sweet a wood?

Could in so chaste demeanour lurk untruth?

Could vice lie hid where virtue’s image stood?

Where hoary sageness graced tender youth?

Where can affiance rest to rest secure?

In virtue’s fairest seat faith is not sure.

All proofs did promise hope, a pledge of grace,

Whose good might have repaid the deepest ill.

Sweet signs of purest thoughts in saintly face

Assured the eye of her unstained will.

Yet in this seeming lustre seem to lie

Such crimes for which the law condemns to die.

But Joseph’s word shall never work her woe:

“I wish her leave to live, not doom to die.

Though fortune mine, yet am I not her foe,

She to herself less loving is than I.

The most I will, the lest I can, is this,

Sith none may salve, to shun that is amiss.

Exile my home, the wilds shall be my walk,

Complaints my joy, my music mourning lays,

With pensive griefs in silence will I talk;

Sad thoughts shall be my guides in sorrow’s ways.

This course best suits the care of cureless mind,

That seeks to lose what most it joyed to find.

Like stocked tree whose branches all do fade,

Whose leaves do fall, and perished fruit decay,

Like herb that grows in cold and barren shade,

Where darkness drives all quick’ning heat away,

So must I die, cut from my root of joy,

And thrown in darkest shades of deep annoy.

But who can fly from that his heart doth feel?

What change of place can change implanted pain?

Removing moves no hardness from the steel.

Sick hearts that shift no fits, shift rooms in vain.

Where thought can see, what helps the closed eye?

Where heart pursues, what gains the foot to fly?

Yet still I tread a maze of doubtful end.

I go, I come, she draws, she drives away,

She wounds, she heals, she doth both mar and mend,

She makes me seek and shun, depart and stay.

She is a friend to love, a foe to loathe,

And in suspense I hang between them both.”

Notes and Reference:

A fardel is a package. Affiance is a binding marriage pledge. I have modernized the spelling and added punctuation. Previous poems by Robert Southwell are here and here.

Robert Southwell [2007]: Collected Poems. Edited by Peter Davidson and Anne Sweeney. Manchester, UK: Fyfield Books, pp. 19-21.

Political activists of renown

Recently, I have listed the teachers and writers who have influenced me, along with the managers whom I admire. I now list the politicians and political activists whom I admire. Some of these led conventional political careers, others were community organizers or single-issue advocates, and yet others were spies, or were accused of being such.

Edmund Campion, Robert Persons, Robert Southwell, Thomas Aikenhead, Tom Paine, Abe Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Solomon Plaatje, Franklin Roosevelt, Ted Theodore, John Curtin, Doc Evatt, Richard Sorge, Imre Nagy, Zhou Enlai, Milada Horakova, Bram Fischer, Salvador Allende Gossens, Lyndon Johnson, Donal Lamont, Rudolf Margolius, Gough Whitlam, Helen Suzman, Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Dubcek, Nelson Mandela, Zhao Ziyang, Martin Luther King Jr, Zdenek Mlynar, Mikhail Gorbachev, Vaclav Havel, Michael Schneider, Bella Subbotovskaya, Paul Keating, Vadim Delone, Jes Albert Möller, Barack Obama and Rory Stewart.

Australia (5), Czechoslovakia (5), and South Africa (5) have produced more than their per capita share of political heroes, it would seem, but the distribution no doubt reflects my reading and interests. Of course, it hardly needs to be said that I do not necessarily agree with any or all the views these people have expressed or hold, nor necessarily support all their actions.