While elements of the left turned to revolutionary violence in most countries of the West at the end of the 1960s, three countries experienced this turn to a much greater extent than any other: Germany, Italy, and Japan. This fact has always intrigued me. Why these three? What facts of history or culture link the three? All three endured fascist totalitarian regimes before WW II, but so too did, say, Poland, Hungary, Greece, Portugal, and Spain. The countries of Eastern Europe, however, met the 1960s still under the Soviet imperium, and so opportunities for violent resistance were few, and in any case were unlikely to come from the left. Spain and Portugal and, for a time, Greece, were still under fascism in the post-war period, so opposition tended to aim at enlarging democracy, not at violent resistance. Perhaps that history is a partial explanation, with (some of) the first post-war generation, the 68ers (in German, achtundsechziger) seeking by their armed resistance to absolve their shame at the perceived lack of resistance to fascism of their parents’ generation. Certainly the writings of the Red Army Fraction (RAF), the Red Brigades, and the Japanese Red Army give this as a justification for their turn to violence.

I have always thought that another causal factor in common between these three countries was the absence of alternating left and right governments. With a succession of right-wing and centre-right regimes in Italy and Japan, and right-wing and grand-coalition (right-and-left-together) regimes in Germany, how were views in favour of socialist change able to be represented and heard? Indeed, in the German Federal Republic, the communist party had been declared illegal in 1956, and remained so until its reformation (under a new name) until 1968. And even the USA may not be an exception to this heuristic: In 1968, the candidate of the major party of the left, Hubert Humphrey, was a protagonist for the war in Vietnam (at least in public, and during the election campaign). And while the candidate of the major party of the right, Richard Nixon, had promised during the campaign to end the war, once in office he intensified and extended it. For anyone opposed to the war in Vietnam, the democratic political system appeared to have failed; indeed, one of those who had most publicly opposed the war, Robert Kennedy, had been assassinated. It is interesting in this regard to note that the Weather Underground only adopted armed resistance as a strategy in December 1969, a year after Nixon’s election. In Chantal Mouffe’s agonistic pluralism view of democracy, a key role of political argument and verbal conflict is to bring everyone into the political tent. If some voices, or some views, are excluded by definition or silenced by assassination, we should not then be surprised that those excluded try to burn down the tent.

And perhaps because I like the idea of acting according to (an empirically-grounded) theory of history, I always found the primary argument of the RAF very intriguing: That by engaging in armed resistance to the capitalist state, the revolutionary left would force the state to reveal its essential fascist character, and that this revelation would awaken the consciousness of the proletariat, leading to the revolutionary overthrow of the state. Although intrigued by it, I never found this argument quite compelling: First, it could be argued that a democratic state only has a fascist character in response to, and to the extent of, armed resistance to it. So predictions of its fascist tendencies become self-fulfilling. Second, the history of countries ruled by fascism in the 20th century surely shows that life under totalitarian rule makes organizing and engaging in dissident activities, particularly group-oriented dissident activities, less not more feasible. Third, I believe strongly that not only do ends not usually justify means, but often means vitiate ends. This is the case here: suppose the violent left’s violent resistance had indeed worked in overthrowing the governments they were directed at. What sort of society would have resulted? What we know of the personalities of Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof and their revolutionary colleagues leads me to think that a Cambodia under the Khmer Rouges, rather than a Sweden under Olof Palme, would be a more likely description for life in a West Germany led by the RAF. Thank our stars they failed.

These thoughts are provoked by some recent reading on the subject of leftist urban terrorism in the West, both fiction and non-fiction. The fiction concerns the psychology and consequences of life underground, long after any thrill of plotting and executing armed resistance has passed.

First, a novel about the Angry Brigade (AB), the lite, British version of the Red Army Fraction: Hari Kunzru’s “My Revolutions”. This is a gripping first-person account by someone who had participated in AB actions, and now, 30 years later, is living under an assumed name. His past comes back to him, through some not-fully-explained, but dirty, tricks that British intelligence agencies seem to be running. These dirty actions are (or rather, appear to be) targeted against those who were on the edges of the violent left, but not part of it, who have now risen to prominence in Government (Joschka Fischer comes to mind), and the narrator is used by the shadowy intelligence forces to blackmail or destroy the career of the target of the action. The writing is fluent and plausible, and the tale engrossing. Only occasionally does Kunzru trip: Who ever uses “recurrent” (page 4) in ordinary speech? (Some people may say “recurring”.) Precisely how does the sun beat down like a drummer? (page 10). But most of the novel reads as the words of the protagonist, and not the words of the novelist, indicating that a realistic character has been created by the author’s words.

The same cannot be said for Dana Spiotta’s “Eat the Document”. Although this book too is riveting, it is not nearly as well-written as Kunzru’s book. The story also concerns the later after-life of some formerly violent leftists, presumably once members of the Weather Underground, now living in hiding in the USA, incognito. The story is told through the purported words of multiple narrators, a technique which enables the events to be described from diverse and interesting perspectives. I say “purported” because too often the words and tone of different narrators sound the same. In addition, often a narrator uses expressions which seem quite implausible for that particular narrator, as when the teenage boy Jason speaks of “recondite” personalities in suburbia (page 74): these are not Jason’s words but those of the author.

These works of fiction are partly engrossing to me because I once unwittingly knew a former violent leftist on the lam – the Symbionese Liberation Army’s James Kilgore, whom I knew as John Pape. I wish I could say I’d always suspected him, but that is not the case. Indeed, if anything, I suspected him of being a secret religious believer. He was serious, always intense, and softly-spoken, and ideologically pure to the point of having no sense of humour. The Struggle was all, and life seemed to be all gravitas, with no levitas (at least in my interactions with him. I have no idea how much of this serious demeanor is or was his true self.) Adopting a position as a committed revolutionary is certainly an interesting strategy for a cover; one does not expect underground weathermen to be regular attenders at Trotskyist reading circles, but Pape was. (And he did the homework!) But perhaps someone with a sense of humour does not join a movement of revolutionary violence in the first place, at least not in a democracy.

In the non-fiction category is Susan Braudy’s history of the Boudin family, one of whose members, Kathy Boudin, was a member of the Weather Underground. As with Kunzru’s and Spiotta’s novels, this non-fictional account is also riveting. It is, however, appallingly badly written. For instance, for a history, the book is very fuzzy about dates – when did Jean Boudin die, for example? And much of the text reads like third-hand family anecdotes, perhaps interesting or amusing to the family but not to anyone else. (Aunty Merle always was partial to rhubarb and once asked for it in a restaurant.) And lots of very relevant information is simply not provided, for instance the prison sentences given to Kathy Boudin’s fellow-accused in 1981. As a history book, this is certainly a book.

Finally, a quick report on Hans Kundnani’s superb analysis of the extreme German left, Utopia or Auschwitz: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust. Kundnani argues that there were competing strains within the violent German left in the 1960s and 1970s: one strain engaged in struggle (against capitalist and western imperialist injustice) as a form of remedy for the failure – or at least, the perceived failure – of their parents’ generation to resist Nazism, and other strains comprising German-nationalist and, suprisingly, even anti-semitic tendencies. The presence of such tendencies at least explains how some on the far left in the 1960s ended up on the neo-Nazi right thirty years later. Kundnani’s book is superb – interesting, well-written, humane, engrossing, and tightly-argued. I had only one small quibble, which is perhaps a typo or an oversight: On page 252, Kundnani refers to German military participation in a NATO-led attack on Serbian forces on 24 March 1999 as the “first time since 1945, Germany was at war.” Well, the Federal Republic of Germany perhaps. The DDR sent troups to join the Warsaw Pact invasion of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in August 1968. If I was a former citizen of the DDR, regardless of my opposition to that invasion, I would be annoyed that my nation’s history seems to have been forgotten by people writing after unification on German history.

UPDATE (2010-08-25): My remark about participation by the DDR military in the Warsaw Pact invasion of the CSSR in 1968 is wrong. The forces of the DDR were, at the last moment, stayed, as I explain here. Thanks to Hans Kundnani for correcting me on this (see comment below).

References:

Bill Ayers [2001]: Fugitive Days: A Memoir. Boston, MA, USA: Beacon Press.

Dan Berger [2006]: Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. Oakland, CA, USA: AK Press.

Susan Braudy [2003]: Family Circle: The Boudins and the Aristocracy of the Left. New York, NY, USA; Anchor Books.

Uli Edel [Director, 2008]: Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex. Germany.

Ron Jacob [1997]: The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground. London, UK: Verso.

Hans Kundnani[2009]: Utopia or Auschwitz: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust. London, UK: Hurst and Company.

Hari Kunzru[2007]: My Revolutions. London, UK: Penguin.

Chantal Mouffe[1993]: The Return of the Political. London, UK: Verso.

Dana Spiotta[2006]: Eat the Document. New York: Scribner/London, UK: Picador.

Tom Vague [1988/2005]: The Red Army Faction Story 1963-1993. San Francisco: AK Press.

Jeremy Varon [2004]: Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Some previous thoughts on beating terrorism here. Past entries in the Recent Reading series are here.

Archive for the ‘Literature’ Category

Page 5 of 5

Concat 3: On writing

For procrastinators among you writing the Great American Novel, here are some links with advice on writing:

- Hilary Mantel [2010]: The joys of stationery. The Guardian, 2010-03-06. On why writers need to keep loose-leaf notebooks. An excerpt:

That said, le vrai moleskine and its mythology irritate me. Chatwin, Hemingway: has the earth ever held two greater posers? The magic has surely gone out of the little black tablet now that you can buy it everywhere, and in pastel pink, and even get it from Amazon – if they believe your address exists. The trouble with the Moleskine is that you can’t easily pick it apart. This may have its advantages for glamorous itinerants, who tend to be of careless habit and do not have my access to self-assembly beech and maple-effect storage solutions – though, as some cabinets run on castors, I don’t see what stopped them filing as they travelled. But surely the whole point of a notebook is to pull it apart, and distribute pieces among your various projects? There is a serious issue here. Perforation is vital – more vital than vodka, more essential to a novel’s success than a spellchecker and an agent.

I often sense the disappointment when trusting beginners ask me how to go about it, and I tell them it’s all about ring binders.”

- Rachel Cusk [2010]: Can creative writing ever be taught? The Guardian, 2010-01-30. A moving discussion on teaching creative writing, and the relationship between writing and therapy.

Honest criticism, I suppose, has its place. But honest writing is infinitely more valuable.

At the start of last term, I asked my students a question: “How did you become the person you are?” They answered in turn, long answers of such startling candour that the photographer who had come in to take a couple of quick pictures for the university magazine ended up staying for the whole session, mesmerised. I had asked them to write down three or four words before they spoke, each word indicating a formative aspect of experience, and to tell me what the words were. They were mostly simple words, such as “father” and “school” and “Catherine”. To me they represented a regression to the first encounter with language; they represented a chance to reconfigure the link between the mellifluity of self and the concreteness of utterance. It felt as though this was a good thing for even the most accomplished writer to do. Were the students learning anything? I suppose not exactly. I’d prefer to think of it as relearning. Relearning how to write; remembering how.

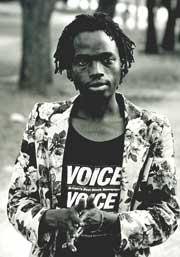

Caute on Marechera

You did not have to visit many bars or nightclubs in downtown Harare in the early 1980s before encountering the late Dambudzo Marechera (1952-1987), Zimbabwean novelist and poet. I knew him slightly, as did anyone who was willing to share a drink with him and enjoy (or endure) a stimulating late-night argument on politics or literature. Some of his writing, for all its coarse language, is powerful and sublime (in the tradition of Burroughs and Genet). David Caute, in a book I have just read, argues correctly that he was a great writer.

The book also captures his personality well, even if it gives the impression that Caute thinks the work forgives the man. It does not. As a person, Marechera was a victim of his addictions and perhaps also of a psychosis – mercurial, abusive, racist, foul-mouthed, illogical, self-destructive, and paranoid: not someone who was nice to be around for very long. Nothing forgives such poor behaviour, not even great writing.

As always when I read David Caute, I am reminded of Graham Greene: both are writers who grapple with the major moral questions and issues of our time, yet both write in the sloppiest of language, insincere and vague, and have the tinnest of ears. Woolly writing might be evidence of woolly thinking or evidence of malice aforethought (perhaps attempting to hide or obfuscate something, as Orwell argued); it could also be evidence of insufficient thinking. In any case, Greene’s and Caute’s arguments are often undone and undermined by their style. We only get as far as page 6 of Caute’s book on Marechera, for example, before we stumble over:

Piled high at the central counter of the Book Fair are copies of his [Marechera’s] new book, Mindblast, published by College Press of Harare, an orange coloured paperback with a surrealist design involving a humanized cat and a black in a space helmet.”

A black what, Dr Caute? A black what? I guess you mean a black person. Just two sentences later, though, you speak of, “An effusive white executive of College Press . . .” So, let me get this right – white people are important enough to have nouns to denote them, but black people not, eh? Hmmm.

Although the effect is racist, I am sure Caute is not deliberately being racist in his use of language here, but rather just sloppy. But the sloppy expression, here as elsewhere, leads one to doubt his sincerity and/or his ear. Of course, someone who spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians could easily forget how offensive the first usage sounds (and is); and we know from Caute’s earlier books that he spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians.

Pressing on, on page 43 we read:

Such rhetoric counts for little against the current surplus of maize, tobacco and beef which only the commercial farmers can guarantee.”

Well, actually, no, Dr Caute. Tobacco and beef were in surplus at the time referred to (1984) due to commercial (ie, mainly white-owned) farms. But maize was in surplus because the avowedly Marxist government of Robert Mugabe used the price mechanism when it came to power to encourage communal farmers (ie, subsistence black farmers) to produce and sell surplus maize crops. This was something so very remarkable – the country in food surplus for its staple food almost immediately after 13 years of civil war and 90 years of insurrection, and because of the fast responsiveness of peasant farmers – that all the papers were full of it. Surely Caute must have heard. (See Herbst 1990 for an account.)

And even beef production was boosted by contributions from communal farmers, particularly after the Government decided not to prosecute the many illegal butcheries competing against the state-owned meat-processing monopoly, the Cold Storage Commission. (One may wonder why a socialist government would not support its own state enterprise against privately-owned competitors until one learns that many members of the Cabinet had financial stakes in the competing butcheries.)

Is the sloppiness in Caute’s sentence then due to Orwellian sleight-of-hand – seeking to promote a case that was factually incorrect – or just due to insufficiently-careful thought? I suspect the latter, although it is throwaway lines like this – as it happens, lines so common in the conversation of white Rhodesians in the 1980s – that make me ponder the sincerity of Caute’s writing.

And, finally, Caute seems eager to berate the left and liberals for their failure to call attention to Robert Mugabe’s ethnic cleansing in Matebeleland in 1982-84, the Gukurahundi campaign. Certainly more could have been said and done, especially publicly, to oppose this. But why is only one side of politics to blame? Both the US and the UK had conservative administrations at the time, both of which (particularly Thatcher’s) made strong representations to Mugabe over the fate of several white Zimbabwe Air Force officers detained and tortured in 1982. These governments did not make nearly such strong representations over the fate of the victims of the Gukurahundi. Perhaps Mugabe was right to accuse the west of racism on this.

And Mugabe’s military campaign in Matabeleland was not launched for no reason: As Caute must know, South Africa and its white Rhodesian friends were engaged in a campaign of terrorist violence against Zimbabwe from its inception, with terrorist bombings throughout the 1980s. The Independence Arch he describes traveling under on the way to Harare Airport was in fact the second arch built to commemorate Independence: the first had been blown up shortly after it was built. And even Joshua Nkomo admitted (at a press conference following his dismissal from Cabinet in February 1982) that he had asked South Africa for assistance to stage a coup after Independence. While Mugabe’s 5th Brigade was certainly engaged in brutal and genocidal murder and rape, the campaign was not against an imaginary enemy.

Although evil may triumph when good people do nothing, from the fact of the triumph of evil it is invalid to infer that nothing was done to oppose it by good people. Where are the mentions in Caute’s account of the strong, high-level and repeated Catholic opposition (both clerical and lay) to Mugabe’s campaign? Where is the mention, in the statement that Mugabe detained people using renewals of Smith’s emergency powers regulations, of the independent review panel established by ZANU(PF) stalwart Herbert Ushewokunze when Minister for Home Affairs, the Detention Review Tribunal, to consider the cases of people detained without trial? The members of this panel included independent lawyers, some of whom were white and liberal. Some people, even some of the people Caute seems to excoriate, were doing their best to stop or ameliorate the evil at the time.

References:

David Caute [1986/2009]: Marechera and the Colonel: A Zimbabwean Writer and the Claims of the State. London, UK: Totterdown Books. Revised edition, 2009.

Jeffrey Herbst [1990]: State Politics in Zimbabwe. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press. Perspectives on Southern Africa Series, Volume 45.

Five minutes of freedom

Jane Gregory, speaking in 2004, on the necessary conditions for a public sphere:

To qualify as a public, a group of people needs four characteristics. First, it should be open to all and any: there are no entry qualifications. Secondly, the people must come together freely. But it is not enough to simply hang out – sheep do that. The third characteristic is common action. Sheep sometimes all point in the same direction and eat grass, but they still do not qualify as a public, because they lack the fourth characteristic, which is speech. To qualify as a public, a group must be made up of people who have come together freely, and their common action is determined through speech: that is, through discussion, the group determines a course of action which it then follows. When this happens, it creates a public sphere.

There is no public sphere in a totalitarian regime – for there, there is insufficient freedom of action; and difference is not tolerated. So there are strong links between the idea of a public sphere and democracy.”

I would add that most totalitarian states often force their citizens to participate in public events, thus violating two basic human rights: the right not to associate and the right not to listen.

I am reminded of a moment of courage on 25 August 1968, when seven Soviet citizens, shestidesiatniki (people of the 60s), staged a brave public protest at Lobnoye Mesto in Red Square, Moscow, at the military invasion of Czechoslovakia by forces of the Warsaw Pact. The seven (and one baby) were: Konstantin Babitsky (mathematician and linguist), Larisa Bogoraz (linguist, then married to Yuli Daniel), Vadim Delone (also written “Delaunay”, language student and poet), Vladimir Dremlyuga (construction worker), Victor Fainberg (mathematician), Natalia Gorbanevskaya (poet, with baby), and Pavel Litvinov (mathematics teacher, and grandson of Stalin’s foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov). The protest lasted only long enough for the 7 adults to unwrap banners and to surprise onlookers. The protesters were soon set-upon and beaten by “bystanders” – plain clothes police, male and female – who then bundled them into vehicles of the state security organs. Ms Gorbanevskaya and baby were later released, and Fainberg declared insane and sent to an asylum.

The other five faced trial later in 1968, and were each found guilty. They were sent either to internal exile or to prison (Delone and Dremlyuga) for 1-3 years; Dremlyuga was given additional time while in prison, and ended up serving 6 years. At his trial, Delone said that the prison sentence of almost three years was worth the “five minutes of freedom” he had experienced during the protest.

Delone (born 1947) was a member of a prominent intellectual family, great-great-great-grandson of a French doctor, Pierre Delaunay, who had resettled in Russia after Napoleon’s defeat. Delone was the great-grandson of a professor of physics, Nikolai Borisovich Delone (grandson of Pierre Delaunay), and grandson of a more prominent mathematician, Boris Nikolaevich Delaunay (1890-1980), and son of physicist Nikolai Delone (1926-2008). In 1907, at the age of 17, Boris N. Delaunay organized the first gliding circle in Kiev, with his friend Igor Sikorski, who was later famous for his helicopters. B. N. Delaunay was also a composer and artist as a young man, of sufficient talent that he could easily have pursued these careers. In addition, he was one of the outstanding mountaineers of the USSR, and a mountain and other features near Mount Belukha in the Altai range are named for him.

Boris N. Delaunay was primarily a geometer – although he also contributed to number theory and to algebra – and invented Delaunay triangulation. He was a co-organizer of the first Soviet Mathematics Olympiad, a mathematics competition for high-school students, in 1934. One of his students was Aleksandr D. Alexandrov (1912-1999), founder of the Leningrad School of Geometry (which studies the differential geometry of curvature in manifolds, and the geometry of space-time). Vadim Delone also showed mathematical promise and was selected to attend Moskovskaya Srednyaya Fiz Mat Shkola #2, Moscow Central Special High School No. 2 for Physics and Mathematics (now the Lyceum “Second School”). This school, established in 1958 for mathematically-gifted teenagers, was famously liberal and tolerant of dissent. (Indeed, so much so that in 1971-72, well after Delone had left, the school was purged by the CPSU. See Hedrick Smith’s 1975 account here. Other special schools in Moscow focused on mathematics are #57 and #179. In London, in 2014, King’s College London established a free school, King’s Maths School, modelled on FizMatShkola #2.) Vadim Delone lived with Alexandrov when, serving out a one-year suspended sentence which required him to leave Moscow, he studied at university in Novosibirsk, Siberia. At some risk to his own academic career, Alexandrov twice bravely visited Vadim Delone while he was in prison.

Delone’s wife, Irina Belgorodkaya, was also active in dissident circles, being arrested both in 1969 and again in 1973, and was sentenced to prison terms each time. She was the daughter of a senior KGB official. After his release in 1971 and hers in 1975, Delone and his wife emigrated to France in 1975, and he continued to write poetry. In 1983, at the age of just 35, he died of cardiac arrest. Given his youth, and the long lives of his father and grandfather, one has to wonder if this event was the dark work of an organ of Soviet state security. According to then-KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov’s report to the Central Committee of the CPSU on the Moscow Seven’s protest in September 1968, Delone was the key link between the community of dissident poets and writers on the one hand, and that of mathematicians and physicists on the other. Andropov even alleges that physicist Andrei Sakharov’s support for dissident activities was due to Delone’s personal persuasion, and that Delone lived from a so-called private fund, money from voluntary tithes paid by writers and scientists to support dissidents. (Sharing of incomes in this way sounds suspiciously like socialism, which the state in the USSR always determined to maintain a monopoly of.) That Andropov reported on this protest to the Central Committee, and less than a month after the event, indicates the seriousness with which this particular group of dissidents was viewed by the authorities. That the childen of the nomenklatura, the intelligentsia, and even the KGB should be involved in these activities no doubt added to the concern. If the KGB actually believed the statements Andropov made about Delone to the Central Committee, they would certainly have strong motivation to arrange his early death.

Several of the Moscow Seven were honoured in August 2008 by the Government of the Czech Republic, but as far as I am aware, no honour or recognition has yet been given them by the Soviet or Russian Governments. Although my gesture will likely have little impact on the world, I salute their courage here.

I have translated a poem of Delone’s here. An index to posts on The Matherati is here.

References:

M. V. Ammosov [2009]: Nikolai Borisovich Delone in my Life. Laser Physics, 19 (8): 1488-1490.

Yuri Andropov [1968]: The Demonstration in Red Square Against the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia. Report to the Central Committee of the CPSU, 1968-09-20. See below.

N. P. Dolbilin [2011]: Boris Nikolaevich Delone (Delaunay): Life and Work. Proceedings of the Steklov Institute of Mathematics, 275: 1-14. Published in Russian in Trudy Matematicheskogo Instituta imeni V. A. Steklov, 2011, 275: 7-21. Pre-print here.

Jane Gregory [2004]: Subtle signs that divide the public from the private. The Independent, 2004-05-20.

Hedrick Smith [1975]: The Russians. Crown. pp. 211-213.

APPENDIX

Andropov Reoport to the Central Committee of the CPSU on the protests in Red Square. (20 September 1968)

In characterizing the political views of the participants of the group, in particular DELONE, our source notes that the latter, “calling himself a bitter opponent of Soviet authority, fiercely detests communists, the communist ideology, and is entirely in agreement with the views of Djilas. In analyzing the activities . . . of the group, he (DELONE) explained that they do not have a definite program or charter, as in a formally organized political opposition, but they are all of the common opinion that our society is not developing normally, that it lacks freedom of speech and press, that a harsh censorship is operating, that it is impossible to express one’s opinions and thoughts, that democratic liberties are repressed. The activity of this group and its propaganda have developed mainly within a circle of writers, poets, but it is also enveloping a broad circle of people working in the sphere of mathematics and physics. They have conducted agitation among many scholars with the objective of inducing them to sign letters, protests, and declarations that have been compiled by the more active participants in this kind of activity, Petr IAKIR and Pavel LITVINOV. These people are the core around which the above group has been formed . . .. IAKIR and LITVINOV were the most active agents in the so-called “samizdat.”

This same source, in noting the condition of the arrested DELONE in this group, declared: “DELONE . . . has access to a circle of prominent scientists, academicians, who regarded him as one of their own, and in that way he served . . . to link the group with the scientific community, having influence on the latter and conducting active propaganda among them. Among his acquaintances he named academician Sakharov, who was initially cautious and distrustful of the activities of IAKIR, LITVINOV, and their group; he wavered in his position and judgments, but gradually, under the influence of DELONE’s explanations, he began to sign various documents of the group. . . ; [he also named] LEONTOVICH, whose views coincide with those of the group. In DELONE’s words, many of the educated community share their views, but are cautious, fearful of losing their jobs and being expelled from the party.” . . . [more details on DELONE]

Agents’ reports indicate that the participants of the group, LITVINOV, DREMLIUGA, AND DELONE, have not been engaged in useful labor for an extended period, and have used the means of the so-called “private fund,” which their group created from the contributions of individual representatives in the creative intelligentsia and scientists.

The prisoner DELONE told our source: “We are assisted by monetary funds from the intelligentsia, highly paid academicians, writers, who share the views of the Iakir-Litvinov group . . . [Sic] We have the right to demand money, [because] we are the functionaries, while they share our views, [but] fear for their skins, so let them support us with money.”

Writing Shakespeare

Since the verified facts of Shakespeare’s life are so few, even a person normally skeptical of conspiracy theories could well consider it possible that the plays and poetry bearing the name of William Shakespeare were written by A. N. Other. But just who could have been that other?

Well, even with few verified facts about Shakespeare’s life, we can know some facts about the author of these texts by reading the texts themselves. Whoever was the author must have spent a lot of time hanging about with actors, since knowledge of, and in-jokes about, acting and the theatre permeate the plays. Also, whoever it was must have grown up in a rural district, not in a big city, since the author of the plays and the poetry knows a great deal about animals and plants, about rural life and its myths and customs, and rural pursuits. Whoever it was also had close connections to Warwickshire, since the plays contain words specific to that area.

Also, whoever it was must have had close personal or family connections to the old religion (Catholicism), since many of the plays make detailed reference to, or indeed seem to be allegories of, the religious differences of the time (Wilson 2004, Asquith 2005). Whoever it was was close enough to the English court to write plays which discussed current political issues using historically-relevant allegories, yet not so close that these plays themselves or their performances (with just one exception) were seen as interventions in court intrigues.

Whoever it was also knew well the samizdat poetry of Robert Southwell, poet and Jesuit martyr, since some of the poetry and plays respond directly to Southwell’s poetry and prose (Wilson 2004, Klause 2008). To have responded to Southwell’s writing before 1595, as the writer of Shakespeare’s narrative poems and early plays did, required access to Southwell’s unpublished, illegal, dissident manuscripts. Southwell and Shakespeare were cousins (Klause 2008 has a family tree).

And finally whoever it was was not a playwright or poet already known to us, since these texts differ stylistically from all other written work of the period, while exhibiting strong stylistic similarity among themselves.

There is only one candidate who fits all these criteria, and his name is William Shakespeare. Anyone seriously proposing an alternative to Shakespeare as the author of Shakespeare’s plays and poetry needs to explain how that person could have written poetry and plays with all the features described above. Every alternative theory so far advanced – Kit Marlowe, the Earl of Oxford, Francis Bacon, Elizabeth I, et al. – falls at the factual hurdles created by the texts themselves.

Note: Klause [2008, p. 40] presents a genealogy which shows that Robert Southwell and William Shakespeare shared a great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Sir Robert Belknap (c. 1330-1401, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas of England, 1377-1388) – Southwell through his mother, Bridget Copley, and Shakespeare through his mother, Mary Arden. In addition, the great-great-grandfather, Sir John Gage, of Shakespeare’s patron, Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, was also grandfather to Edward Gage, husband of Margaret Shelley, Southwell’s mother’s first cousin and, like his mother, a descendant of Sir Robert Belknap. In the extended families of Elizabethan society, all three – Shakespeare, Southwell and Wriothesley – would have been seen as, and would have known each other as, cousins. The bonds across such extended family relationships were strong. Having lived in contemporary societies (in Southern Africa) where extended families still play a prominent role (Bourdillon 1976), the strong loyalty and close brotherhood engendered across such apparently-distant connections is perfectly understandable to me, if not yet to all Shakespeare scholars.

References:

Clare Asquith [2005]: Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. UK: Public Affairs.

Michael F. Bourdillon [1976]: The Shona Peoples: An Ethnography of the Contemporary Shona, with Special Reference to their Religion. Shona Heritage Series. Gwelo, Rhodesia (now Gweru, Zimbabwe): Mambo Press.

John Klause [2008]: Shakespeare, the Earl and the Jesuit. Madison, NJ, USA: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Anne R. Sweeney [2006]: Robert Southwell: Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape 1586-1595. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Richard Wilson [2004]: Secret Shakespeare: Studies in Theatre, Religion and Resistance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Postcards to the future

Designer & blogger Russell Davies has an interesting post about sharing, but he is mistaken about books. He says:

A mixtape is more valuable gift than a spotify playlist because of that embedded value, because everyone knows how much work they are, of the care you have to take, because there is only one. If it gets lost it’s lost. Sharing physical goods is psychically harder than sharing information because goods are more valuable. And, therefore, presumably, the satisfactions of sharing them are greater. I bet there’s some sort of neurological/evolutionary trick in there, physical things will always feel more valuable to us because that’s what we’re used to, that’s what engages our senses. Even though ebooks are massively more convenient, usable and useful than paper ones, that lack of embodiedness nags away at us – telling us that this thing’s not real, not proper, not of value. (And maybe we don’t have the same effect with music because we’re less used to having music engage so many of our senses. It’s pretty unembodied anyway.)

No, it’s not that we value physical objects like books because we are used to doing so, nor (a really silly idea, this) because of some form of long-range evolutionary determinism. (If our pre-literate ancestors only valued physical objects, why did they paint art on cave walls?) No, we value books because they are a tangible reminder to us of the feelings we had while reading them, a souvenir postcard sent from our past self to our future self.

ebooks are only more convenient, usable and useful than paper ones if your purpose to read from start to finish, or to dip into them here and there. If instead, as is usually the case with mathematics books, you need to read some chapters or sections while continually referring back to earlier ones (for example, the chapters with definitions), then a physical book and multiple book-marks is orders of magnitude more convenient, usable and useful than an e-book.

And no African would agree that music is unembodied. You show your appreciation for music you hear by joining in, physically, dancing or singing or tapping a foot or beating a hand in time. Music is actually the most embodied of the arts.

Brautigan on writing

I am a great fan of the writing of Richard Brautigan, so I was delighted once to encounter a short reminiscence of Brautigan by that Zelig of the Beats, Pierre Delattre, in his fascinating memoir, Episodes (page 54):

The last time I saw him [RB], we were walking past the middle room of his house. There was a table in there with a typewriter on it. “Quiet,” he whispered, pushing me ahead of him into the kitchen. “My new novel’s in there. I kind of stroll in occasionally, write a quick few paragraphs, and get out before the novel knows what I’m doing. If novels ever find out you’re writing them, you’re done for.”

Reference:

Pierre Delattre[1993]: Episodes. St. Paul, MN, USA: Graywolf Press.