The latest in a sequence of lists of recently-read books.

David Eagleman [2010]: Sum: Tales from the Afterlives. (London, UK: Canongate). A superb collection of very short stories, each premised on the assumption that something (our bodies, our souls, our names, our molecules, etc) lives beyond death. Superbly fascinating. One will blow your mind! (HT: WPN).

A. C. Grayling [2013]: Friendship. (New Haven, CT and London, UK: Yale University Press).

Andrew Sullivan [1998]: Love Undetectable: Reflections on Friendship, Sex and Survival. (London, UK: Vintage, 1999).

Michael Blakemore [2013]: Stage Blood. (London, UK: Faber & Faber). A riveting account of Blakemore’s time at the National Theatre in London.

Continue reading ‘Recent Reading 10’

Archive for the ‘Fiction’ Category

Page 2 of 2

HoJa do

Howard Jacobson apparently writes comic novels. I have never found his writing funny, and it often strikes me as being in poor taste. (A Jewish anti-Zionist group called “ASH”, for example?) In a review today of his latest novel, Theo Tait puts his finger on what I don’t like about HoJa’s books:

Zoo Time conforms closely to the classic recipe for a Howard Jacobson novel. Take a childless, Jewish middle-aged man, born in Manchester or thereabouts, now living in London pursuing a profession not unlike the author’s: in the past, we’ve had columnists, cartoonists and academics; this time, he’s a novelist, Guy Ableman. Give him ungovernable romantic urges and a powerful but embattled sense of self-worth: Guy, whose first novel stars a zoo keeper and her lustful monkeys, describes himself as “a man ruled by pointless ambition and a blazing red penis”. Throw in some marital difficulties and outré sexual enthusiasms: this one briefly covers the classic Jacobson kinks – shoe fetishism, oedipal fantasy, and the powerful desire to be cuckolded – but focuses chiefly on Guy’s wish to bed his mother-in-law. Add some agitated discussion of Jewish identity. Then stir it all up with a lot of discourse, and of discourse about discourse. Ensure that the plot is minimal, and largely circular. And there it is, the distinctive feel of Jacobson’s work – like being trapped in a confined space with a particularly garrulous pervert.

. . . .

The killer for Zoo Time is that Jacobson has a limited talent for invention, and certainly very little inclination for it. As with many authors possessed of a powerful voice, it tends to crowd out everything else in the novel: “A writer such as I am feels he’s been away from the first person for too long if a third-person narrative goes on for more than two paragraphs …” Guy’s every passing thought is generously and sometimes brilliantly transcribed, but otherwise Jacobson seems to have no idea what to do with his stick people, who couple and uncouple, turn gay or Hasidic, to no discernible pattern.”

The problem with a powerful voice, as the novels of Bellow and Roth also demonstrate, is that you only reach those readers who appreciate the persona behind the voice, and who don’t mind being trapped in a confined space with him. Me? I’ll skip sharing an elevator with Jacobson or Roth or Bellow, and take the stairs, thanks.

POSTSCRIPT (2014-05-18): Ivan Klima in his memoir, My Crazy Century (Grove Press, London, 2014), writes of meeting Philip Roth in communist-ruled Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, and inadvertently captures what is bad about Roth’s (and HoJa’s) fiction:

Philip Roth, the third American prose writer who visited us several times during the first few years after occupation, seemed to me unlike other Americans in one noticeable way: He was not fond of polite, social conversation; he wanted to discuss only what interested him.” (Page 308)

POSTSCRIPT (2015-03-28): Howard Jacobson on his novels: “I was not, in my own eyes, a comic novelist, . . .”. Well here is something we can agree on! To be called a comic novelist, one first has to write novels which are funny.

POSTSCRIPT (2015-06-04): Last weekend, I found myself not ten paces away in the same near-empty room as HoJa, the entrance Hall of King’s College London, where he had come to participate in the Australian and NZ Festival of Literature. I could easily have approached him, but I could think of nothing positive to say.

POSTCRIPT (2018-06-03): In a New Yorker tribute by David Remnick to Philip Roth, who has just died, we read (issue of 4 & 11 June 2018):

“I once asked him [Roth] if he took a week off or a vacation. “I went to the Met and saw a big show they had,” he told me. “It was wonderful. I went back the next day. Great. But what was I supposed to do next, go a third time? So I started writing again.”

Having spent whole days enchanted in just two or three rooms of the Met, I am appalled by the lack of imagination, particularly visual and tactile imagination, expressed by this statement. It summarizes succinctly much of what I dislike about his fiction, all self-obsessed words and no imagination.

Two lists of books

In succession to this post which seems to have originated a meme, herewith two lists of novels – one list influential when younger, and the other later, with influence measured by strength of memory. In each case, I include a couple of works of non-fiction, because of their superb writing.

The rules only allow listing of one book per author. In fact, all the books of some writers would merit inclusion. In this group, I would include Brautigan, Camus, Conrad, Faulkner, Gordimer, Ishiguro, H. James, Joyce, Maugham, Perec and Turgenev.

Influential when younger:

- Albert Camus: The Plague

- JM Coetzee: Waiting for the Barbarians

- Joseph Conrad: The Secret Agent

- William Faulkner: As I Lay Dying

- Nadine Gordimer: Burger’s Daughter

- Joseph Heller: Catch-22

- Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: Heat and Dust

- James Joyce: Ulysses

- Franz Kafka: The Trial

- Arthur Koestler: Darkness at Noon

- William Least Heat-Moon: Blue Highways: A Journey into America

- Doris Lessing: The Diary of a Good Neighbour

- Thomas Mann: Dr Faustus

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez: 100 Years of Solitude

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Razor’s Edge

- Herman Melville: Moby Dick

- Gerald Murnane: Landscape with Landscape

- Michael Ondaatje: Coming Through Slaughter

- Bertrand Russell: The Autobiography

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Nausea

- Mikhail Sholokhov: And Quiet Flows the Don

- Alice Walker: The Color Purple

- Patrick White: Voss

- Yevgeny Zamyatin: We

Influential more recently:

- Henry Adams: The Education of Henry Adams

- Richard Brautigan: An Unfortunate Women: A Journey

- William Burroughs: Naked Lunch

- Italo Calvino: If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller

- Robert Dessaix: Corfu

- Shusaku Endo: Silence

- Mark Henshaw: Out of the Line of Fire

- Kazuo Ishiguro: An Artist of the Floating World

- Henry James: The Princess Casamassima

- Ryszard Kapuscinski: The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat

- Naguib Mahfouz: The Journey of Ibn Fattouma

- Norman Mailer: Harlot’s Ghost

- Alberto Moravia: Boredom

- Georges Perec: Things: A Story of the Sixties

- Antonio Tabucchi: Pereira Maintains

- Henry David Thoreau: Cape Cod

- Ivan Turgenev: Fathers and Sons

- Glenway Wescott: The Pilgrim Hawk

As these lists may indicate, there are some writers (eg, James, Turgenev) whom one may only appreciate after a certain age and passage of years.

On the other hand, for various different reasons, books by the following authors do not speak at all to me.

- The family Amis

- Saul Bellow

- The family Bronte

- Peter Carey

- David Caute

- George Eliot

- Richard Ford

- Graham Greene

- Ernest Hemingway

- Howard Jacobson

- Thomas Keneally

- Milan Kundera (the Benny Hill of Czech literature)

- Iris Murdoch

- Anthony Powell

- Marcel Proust

- Philip Roth

- Tom Sharpe

- Anthony Trollope

- PG Wodehouse

- and many more.

For some of these authors, the issue may be a generational one: for example, I know of no members of late Generation Jones or later-born readers who appreciate that early-Baby Boomer obsession, A Dance to the Music of Time, Powell’s long-winded novel sequence. Added 2013-02-12: The age threshold of my personal sample is confirmed by that of Max Hastings, writing in 2004:

Anthony Powell’s fan club, always far smaller than that of his contemporary Evelyn Waugh, will continue to shrink as admirers die off and are not replaced. Nobody whom I know under 40 reads his books, while Waugh’s position as the greatest English novelist of the 20th century seems secure.”

Of course, not everyone shares my low opinion of Roth’s work.

Concat 3: On writing

For procrastinators among you writing the Great American Novel, here are some links with advice on writing:

- Hilary Mantel [2010]: The joys of stationery. The Guardian, 2010-03-06. On why writers need to keep loose-leaf notebooks. An excerpt:

That said, le vrai moleskine and its mythology irritate me. Chatwin, Hemingway: has the earth ever held two greater posers? The magic has surely gone out of the little black tablet now that you can buy it everywhere, and in pastel pink, and even get it from Amazon – if they believe your address exists. The trouble with the Moleskine is that you can’t easily pick it apart. This may have its advantages for glamorous itinerants, who tend to be of careless habit and do not have my access to self-assembly beech and maple-effect storage solutions – though, as some cabinets run on castors, I don’t see what stopped them filing as they travelled. But surely the whole point of a notebook is to pull it apart, and distribute pieces among your various projects? There is a serious issue here. Perforation is vital – more vital than vodka, more essential to a novel’s success than a spellchecker and an agent.

I often sense the disappointment when trusting beginners ask me how to go about it, and I tell them it’s all about ring binders.”

- Rachel Cusk [2010]: Can creative writing ever be taught? The Guardian, 2010-01-30. A moving discussion on teaching creative writing, and the relationship between writing and therapy.

Honest criticism, I suppose, has its place. But honest writing is infinitely more valuable.

At the start of last term, I asked my students a question: “How did you become the person you are?” They answered in turn, long answers of such startling candour that the photographer who had come in to take a couple of quick pictures for the university magazine ended up staying for the whole session, mesmerised. I had asked them to write down three or four words before they spoke, each word indicating a formative aspect of experience, and to tell me what the words were. They were mostly simple words, such as “father” and “school” and “Catherine”. To me they represented a regression to the first encounter with language; they represented a chance to reconfigure the link between the mellifluity of self and the concreteness of utterance. It felt as though this was a good thing for even the most accomplished writer to do. Were the students learning anything? I suppose not exactly. I’d prefer to think of it as relearning. Relearning how to write; remembering how.

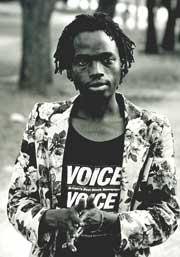

Caute on Marechera

You did not have to visit many bars or nightclubs in downtown Harare in the early 1980s before encountering the late Dambudzo Marechera (1952-1987), Zimbabwean novelist and poet. I knew him slightly, as did anyone who was willing to share a drink with him and enjoy (or endure) a stimulating late-night argument on politics or literature. Some of his writing, for all its coarse language, is powerful and sublime (in the tradition of Burroughs and Genet). David Caute, in a book I have just read, argues correctly that he was a great writer.

The book also captures his personality well, even if it gives the impression that Caute thinks the work forgives the man. It does not. As a person, Marechera was a victim of his addictions and perhaps also of a psychosis – mercurial, abusive, racist, foul-mouthed, illogical, self-destructive, and paranoid: not someone who was nice to be around for very long. Nothing forgives such poor behaviour, not even great writing.

As always when I read David Caute, I am reminded of Graham Greene: both are writers who grapple with the major moral questions and issues of our time, yet both write in the sloppiest of language, insincere and vague, and have the tinnest of ears. Woolly writing might be evidence of woolly thinking or evidence of malice aforethought (perhaps attempting to hide or obfuscate something, as Orwell argued); it could also be evidence of insufficient thinking. In any case, Greene’s and Caute’s arguments are often undone and undermined by their style. We only get as far as page 6 of Caute’s book on Marechera, for example, before we stumble over:

Piled high at the central counter of the Book Fair are copies of his [Marechera’s] new book, Mindblast, published by College Press of Harare, an orange coloured paperback with a surrealist design involving a humanized cat and a black in a space helmet.”

A black what, Dr Caute? A black what? I guess you mean a black person. Just two sentences later, though, you speak of, “An effusive white executive of College Press . . .” So, let me get this right – white people are important enough to have nouns to denote them, but black people not, eh? Hmmm.

Although the effect is racist, I am sure Caute is not deliberately being racist in his use of language here, but rather just sloppy. But the sloppy expression, here as elsewhere, leads one to doubt his sincerity and/or his ear. Of course, someone who spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians could easily forget how offensive the first usage sounds (and is); and we know from Caute’s earlier books that he spent a lot of time in the company of white Rhodesians.

Pressing on, on page 43 we read:

Such rhetoric counts for little against the current surplus of maize, tobacco and beef which only the commercial farmers can guarantee.”

Well, actually, no, Dr Caute. Tobacco and beef were in surplus at the time referred to (1984) due to commercial (ie, mainly white-owned) farms. But maize was in surplus because the avowedly Marxist government of Robert Mugabe used the price mechanism when it came to power to encourage communal farmers (ie, subsistence black farmers) to produce and sell surplus maize crops. This was something so very remarkable – the country in food surplus for its staple food almost immediately after 13 years of civil war and 90 years of insurrection, and because of the fast responsiveness of peasant farmers – that all the papers were full of it. Surely Caute must have heard. (See Herbst 1990 for an account.)

And even beef production was boosted by contributions from communal farmers, particularly after the Government decided not to prosecute the many illegal butcheries competing against the state-owned meat-processing monopoly, the Cold Storage Commission. (One may wonder why a socialist government would not support its own state enterprise against privately-owned competitors until one learns that many members of the Cabinet had financial stakes in the competing butcheries.)

Is the sloppiness in Caute’s sentence then due to Orwellian sleight-of-hand – seeking to promote a case that was factually incorrect – or just due to insufficiently-careful thought? I suspect the latter, although it is throwaway lines like this – as it happens, lines so common in the conversation of white Rhodesians in the 1980s – that make me ponder the sincerity of Caute’s writing.

And, finally, Caute seems eager to berate the left and liberals for their failure to call attention to Robert Mugabe’s ethnic cleansing in Matebeleland in 1982-84, the Gukurahundi campaign. Certainly more could have been said and done, especially publicly, to oppose this. But why is only one side of politics to blame? Both the US and the UK had conservative administrations at the time, both of which (particularly Thatcher’s) made strong representations to Mugabe over the fate of several white Zimbabwe Air Force officers detained and tortured in 1982. These governments did not make nearly such strong representations over the fate of the victims of the Gukurahundi. Perhaps Mugabe was right to accuse the west of racism on this.

And Mugabe’s military campaign in Matabeleland was not launched for no reason: As Caute must know, South Africa and its white Rhodesian friends were engaged in a campaign of terrorist violence against Zimbabwe from its inception, with terrorist bombings throughout the 1980s. The Independence Arch he describes traveling under on the way to Harare Airport was in fact the second arch built to commemorate Independence: the first had been blown up shortly after it was built. And even Joshua Nkomo admitted (at a press conference following his dismissal from Cabinet in February 1982) that he had asked South Africa for assistance to stage a coup after Independence. While Mugabe’s 5th Brigade was certainly engaged in brutal and genocidal murder and rape, the campaign was not against an imaginary enemy.

Although evil may triumph when good people do nothing, from the fact of the triumph of evil it is invalid to infer that nothing was done to oppose it by good people. Where are the mentions in Caute’s account of the strong, high-level and repeated Catholic opposition (both clerical and lay) to Mugabe’s campaign? Where is the mention, in the statement that Mugabe detained people using renewals of Smith’s emergency powers regulations, of the independent review panel established by ZANU(PF) stalwart Herbert Ushewokunze when Minister for Home Affairs, the Detention Review Tribunal, to consider the cases of people detained without trial? The members of this panel included independent lawyers, some of whom were white and liberal. Some people, even some of the people Caute seems to excoriate, were doing their best to stop or ameliorate the evil at the time.

References:

David Caute [1986/2009]: Marechera and the Colonel: A Zimbabwean Writer and the Claims of the State. London, UK: Totterdown Books. Revised edition, 2009.

Jeffrey Herbst [1990]: State Politics in Zimbabwe. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press. Perspectives on Southern Africa Series, Volume 45.

Writing Shakespeare

Since the verified facts of Shakespeare’s life are so few, even a person normally skeptical of conspiracy theories could well consider it possible that the plays and poetry bearing the name of William Shakespeare were written by A. N. Other. But just who could have been that other?

Well, even with few verified facts about Shakespeare’s life, we can know some facts about the author of these texts by reading the texts themselves. Whoever was the author must have spent a lot of time hanging about with actors, since knowledge of, and in-jokes about, acting and the theatre permeate the plays. Also, whoever it was must have grown up in a rural district, not in a big city, since the author of the plays and the poetry knows a great deal about animals and plants, about rural life and its myths and customs, and rural pursuits. Whoever it was also had close connections to Warwickshire, since the plays contain words specific to that area.

Also, whoever it was must have had close personal or family connections to the old religion (Catholicism), since many of the plays make detailed reference to, or indeed seem to be allegories of, the religious differences of the time (Wilson 2004, Asquith 2005). Whoever it was was close enough to the English court to write plays which discussed current political issues using historically-relevant allegories, yet not so close that these plays themselves or their performances (with just one exception) were seen as interventions in court intrigues.

Whoever it was also knew well the samizdat poetry of Robert Southwell, poet and Jesuit martyr, since some of the poetry and plays respond directly to Southwell’s poetry and prose (Wilson 2004, Klause 2008). To have responded to Southwell’s writing before 1595, as the writer of Shakespeare’s narrative poems and early plays did, required access to Southwell’s unpublished, illegal, dissident manuscripts. Southwell and Shakespeare were cousins (Klause 2008 has a family tree).

And finally whoever it was was not a playwright or poet already known to us, since these texts differ stylistically from all other written work of the period, while exhibiting strong stylistic similarity among themselves.

There is only one candidate who fits all these criteria, and his name is William Shakespeare. Anyone seriously proposing an alternative to Shakespeare as the author of Shakespeare’s plays and poetry needs to explain how that person could have written poetry and plays with all the features described above. Every alternative theory so far advanced – Kit Marlowe, the Earl of Oxford, Francis Bacon, Elizabeth I, et al. – falls at the factual hurdles created by the texts themselves.

Note: Klause [2008, p. 40] presents a genealogy which shows that Robert Southwell and William Shakespeare shared a great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Sir Robert Belknap (c. 1330-1401, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas of England, 1377-1388) – Southwell through his mother, Bridget Copley, and Shakespeare through his mother, Mary Arden. In addition, the great-great-grandfather, Sir John Gage, of Shakespeare’s patron, Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, was also grandfather to Edward Gage, husband of Margaret Shelley, Southwell’s mother’s first cousin and, like his mother, a descendant of Sir Robert Belknap. In the extended families of Elizabethan society, all three – Shakespeare, Southwell and Wriothesley – would have been seen as, and would have known each other as, cousins. The bonds across such extended family relationships were strong. Having lived in contemporary societies (in Southern Africa) where extended families still play a prominent role (Bourdillon 1976), the strong loyalty and close brotherhood engendered across such apparently-distant connections is perfectly understandable to me, if not yet to all Shakespeare scholars.

References:

Clare Asquith [2005]: Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. UK: Public Affairs.

Michael F. Bourdillon [1976]: The Shona Peoples: An Ethnography of the Contemporary Shona, with Special Reference to their Religion. Shona Heritage Series. Gwelo, Rhodesia (now Gweru, Zimbabwe): Mambo Press.

John Klause [2008]: Shakespeare, the Earl and the Jesuit. Madison, NJ, USA: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Anne R. Sweeney [2006]: Robert Southwell: Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape 1586-1595. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Richard Wilson [2004]: Secret Shakespeare: Studies in Theatre, Religion and Resistance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Computer science, love-child: Part 2

This post is a continuation of the story which began here.

Life for the teenager Computer Science was not entirely lonely, since he had several half-brothers, half-nephews, and lots of cousins, although he was the only one still living at home. In fact, his family would have required a William Faulkner or a Patrick White to do it justice.

The oldest of Mathematics’ children was Geometry, who CS did not know well because he did not visit very often. When he did visit, G would always bring a sketchpad and make drawings, while the others talked around him. What the boy had heard was that G had been very successful early in his life, with a high-powered job to do with astronomy at someplace like NASA and with lots of people working for him, and with business trips to Egypt and Greece and China and places. But then he’d had an illness or a nervous breakdown, and thought he was traveling through the fourth dimension. CS had once overheard Maths telling someone that G had an “identity crisis“, and could not see the point of life anymore, and he had become an alcoholic. He didn’t speak much to the rest of the family, except for Algebra, although all of them still seemed very fond of him, perhaps because he was the oldest brother.

Continue reading ‘Computer science, love-child: Part 2’

Computer Science, love-child

With the history and pioneers of computing in the British news this week, I’ve been thinking about a common misconception: many people regard computer science as very closely related to Mathematics, perhaps even a sub-branch of Mathematics. Mathematicians and physical scientists, who often know little and that little often outdated about modern computer science and software engineering, are among the worst offenders here. For some reason, they often think that computer science consists of Fortran programming and the study of algorithms, which has been a long way from the truth for, oh, the last few decades. (I have past personal experience of the online vitriol which ignorant pure mathematicians can unleash on those who dare to suggest that computer science might involve the application of ideas from philosophy, economics, sociology or ecology.)

So here’s my story: Computer Science is the love-child of Pure Mathematics and Philosophy.

Continue reading ‘Computer Science, love-child’