Suppose you are diagnosed with a serious medical condition, and you seek advice from two doctors. The first doctor, let’s call him Dr Barack, says that there are three possible courses of treatment. He labels these courses, A, B and C, and then proceeds to walk you methodically through each course – what separate basic procedures are involved, in what order, with what likely side effects, and with what costs and durations, what chances of success or failure, and what likely survival rates. He finishes this methodical exposition by summing up each treatment, with pithy statements such as, “Course A is the cheapest and most proven. Course B is an experimental treatment, which makes it higher risk, but it may be the most effective. Course C . . .” etc.

The other doctor, let’s call him Dr John, in contrast talks in a manner which is apparently lacking all structure. He begins a long, discursive narrative about the many different basic procedures possible, not in any particular order, jumping back and forth between these as he focuses first on the costs of procedures, then switching to their durations, then back again to costs, then onto their expected side effects, with tangential discussions in the middle about the history of the experimental tests undertaken of one of the procedures and about his having suffered torture while a POW in Vietnam, etc, etc. And he does all this without any indication that some procedures are part of larger courses of treatment, or are even linked in any way, and speaking without using any patient-friendly labelling or summarizing of the decision-options.

Which doctor would you choose to treat you? If this description was all that you knew, then Doctor Barack would appear to be the much better organized of the two doctors. Most of us would have more confidence being treated by a doctor who sounds better-organized, who appears to know what he was doing, compared to a doctor who sounds dis-organized. More importantly, it is also evident that Doctor Barack knows how to structure what he knows into a coherent whole, into a form which makes his knowledge easier to transmit to others, easier for a patient to understand, and which also facilitates the subsequent decision-making by the patient. We generally have more confidence in the underlying knowledge and expertise of people able to explain their knowledge and expertise well, than in those who cannot.

If we reasoned this way, we would be choosing between the two doctors on the basis of their different rhetorical styles: we would be judging the contents of their arguments (in this case, the content is their ability to provide us with effective treatment) on the basis of the styles of their arguments. Such reasoning processes, which use form to assess content, are called epideictic, as are arguments which draw attention to their own style.

Advertising provides many examples of epideictic arguments, particularly in cultures where the intended target audience is savvy regarding the form of advertisements. In Britain, for instance, the film director Michael Winner starred in a series of TV advertisements for an insurance company in which the actors pretending to be real people giving endorsements revealed that they were just actors, pretending to be real people giving endorsements. This was a glimpse behind the curtain of theatrical artifice, with the actors themselves pulling back the curtain. Why do this? Well, self-reference only works with a knowledgeable audience, perhaps so knowledgeable that they have even grown cynical with the claims of advertisers. By winking at the audience, the advertisers are colluding with this cynicism, saying to the audience, “we know you think this and we agree, so our advert is pitched to you, you cynical sophisticates, not to those others who don’t get it.”

The world-weary tone of the narration of Apple’s “Future” series of adverts here is another example of advertisements which knowingly direct our attention to their own style.

Apple Future Advertisement – Robots

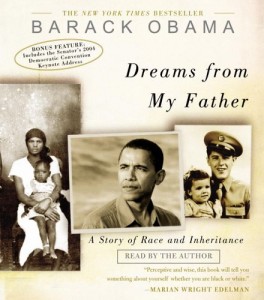

And Dr Barack and Dr John? One argument against electing Senator Obama to the US Presidency was that he lacked executive experience. A counter-argument, made even by the good Senator Obama himself, was that he demonstrated his executive capabilities through the competence, professionalism and effectiveness of his management of his own campaign. This is an epideictic argument.

There is nothing necessarily irrational or fallacious about such arguments or such modes of reasoning; indeed, it is often the case that the only relevant information available for a decision on a claim of substantive content is the form of the claim. Experienced investors in hi-tech start-ups, for example, know that the business plan they are presented with is most unlikely to be implemented, because the world changes too fast and too radically for any plan to endure. A key factor in the decision to invest must therefore be an assessment of the capability of the management team to adjust the business plan to changing circumstances, from recognizing that circumstances have in fact changed, to acting quickly and effectively in response, through to evaluating the outcomes.

How to assess this capability for decision-making robustness? Well, one basis is the past experience of the team. But experience may well hinder managerial flexibility rather than facilitate it, especially in a turbulent environment. Another way to assess this capability is to subject the team to a stress test – contesting the assumptions and reasoning of the business plan, being unreasonable in questions and challenges, prodding and poking and provoking the team to see how well and how quickly they can respond, in real time, without preparation. In all of this, a decision on the substance of the investment is being made from evidence about the form – about how well the management team responds to such stress testing. This is perfectly rational, given the absence of any other basis on which to make a decision and given our imperfect knowledge of the future.

Likewise, an assessment of Senator Obama’s capabilities for high managerial office on the basis of his competence at managing his campaign was also eminently rational and perfectly justifiable. The incoherent nature of Senator McCain’s campaign and the panic-struck and erratic manner in which he responded to surprising events (such as the financial crisis of September 2008) was similarly an indication of his likely style of government; the style here did not produce confidence in the content. For many people, the choice between candidates in the US Presidential campaign was an epideictic one.

POSTSCRIPT (2011-12-14):

Over at Normblog, Norm has a nice example of epideictic reasoning: deciding between two arguments on the basis of how the arguments were made (presented), rather than by their content. As always with such reasoning – and contrary to much educated opinion – such reasoning can be perfectly rational, as is the case here.

PS2 (2016-09-05):

John Lanchester in a book review of a book about investor activism gives a nice example of attempting to influence people’s opinions using epideictic means: Warren Buffet’s annual letters to investors in Berkshire Hathaway:

Even the look of the letters – deliberately plain to the point of hokiness, with old-school fonts and layout hardly changed in fifty years – is didactic. The message is: no flash here, only substance. Go to the company’s Web site, arguably the ugliest in the world, and you are greeted by “A Message from Warren E. Buffet” telling you that he doesn’t make stock recommendations but that you will save money by insuring your car with GEICO and buying your jewelry from Borsheims.” (page 78)

PS3 (2017-04-02):

Dale Russakof, in a New Yorker profile of now-Senator Cory Booker, says:

Over lunch at Andros Diner, Booker told me that [fellow Yale Law School student Ed] Nicoll taught him an invaluable lesson: “Investors bet on people, not on business plans, because they know successful people will find a way to be successful.” (page 60)

Refs and Acks

The medical example is due to William Rehg.

John Lanchester [2016]: Cover letter. New Yorker, 5 September 2016, pp.76-79.

William Rehg [1997]: Reason and rhetoric in Habermas’s theory of argumentation, pp. 358-377 in: W. Jost and M. J. Hyde (Editors): Rhetoric and Hermeneutics in Our Time: A Reader. New Haven, CN, USA: Yale University Press.

Dale Russakoff [2014]: Schooled. The New Yorker, 19 May 2014, pp. 58-73.