The philosopher George Santayana (1863-1952), whom I have written about before, was fortunate to have two families, one Spanish and one American. His mother was a widow when she married his father, and his parents later preferred to live in different countries – the USA and Spain, respectively. Santayana therefore spent part of his childhood with each, and accordingly grew up knowing his Bostonian step-family and their cousins, relatives of his mother’s first husband, the American Sturgis family. Among these relatives, his step-cousin Susan Sturgis (1846-1923) is mentioned briefly in Santayana’s 1944 autobiography (page 80). (See Footnote #1 below.)

Susan Sturgis was married twice, the second time in 1876 to Henry Bigelow Williams (1844-1912), a widower and property developer. In 1890, Williams commissioned a stained glass window from Louis Tiffany for the All Souls Unitarian Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts (pictured below), to commemorate his first wife, Sarah Louisa Frothingham (1851-1871).

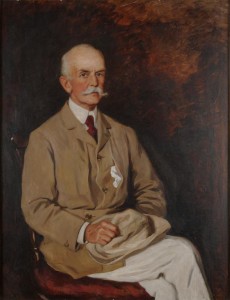

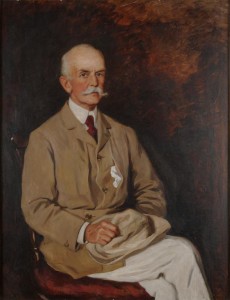

The first marriage of Susan Sturgis was in 1867, to Henry Horton McBurney (1843-1875). McBurney’s younger brother, Charles Heber McBurney (1845-1913) went on to fame as a surgeon, developer of the procedure for diagnosis of appendicitis and removal of the appendix. The normal place of incision for an appendectomy is known to every medical student still as McBurney’s Point. The portrait below of Charles Heber McBurney was painted in 1911 by Ellen Emmet Rand (1875-1941), and is still in the possession of the McBurney family. (The painting is copyright Gerard McBurney 2013. As Ellen Emmet married William Blanchard Rand in 1911, this is possibly the first painting she signed with her married name.)

Charles H. McBurney was also a member of the medical team which treated US President William McKinley following his assassination. He and his wife, Margaret Willoughby Weston (1846-1909), had two sons, Henry and Malcolm, and a daughter, Alice. The younger son, Malcolm, also became a doctor and married, having a daughter, but he died young. Alice McBurney married Austen Fox Riggs (1876-1940), a protege of her father, Charles, and a pioneer of psychiatry. He founded what is now the Austen Riggs Centre in Stockbridge, MA, in 1907. They had two children, one of whom, Benjamin Riggs (c.1914-1992), was also a distinguished psychiatrist, as well as a musician, sailor, and boat builder. The elder son of Charles and Margaret, Henry McBurney (1874-1956), was an engineer whose own son, Charles Brian Montagu McBurney (1914-1979), became a famous Cambridge University archaeologist. CBM’s children are the composer Gerard McBurney, the actor/director Simon McBurney OBE, and the art-historian, Henrietta Ryan FLS, FSA. CBM’s sister, Daphne (1912-1997), married Richard Farmer. Their four children were Angela Farmer, a yoga specialist, David Farmer FRS, a distinguished oceanographer, whose daughter Delphine Farmer, is a chemist, Michael Farmer, painting conservator, and Henry Farmer, an IT specialist, whose son, Olivier Farmer, is a psychiatrist.

Henry H. and Charles H. had three sisters, Jane McBurney (born 1835 or 1836), Mary McBurney (1839- ), Almeria McBurney (who died young), and another brother, John Wayland McBurney (1848-1885). They were born in Roxbury, MA, to Charles McBurney and Rosina Horton; Charles senior (1803 Ireland – Boston 1880) was initially a saddler and harness maker in Tremont Row, Boston – the image above shows a label from a trunk he made. Later, he was a pioneer of the rubber industry, for example, receiving a patent in 1858 for elastic pipe, and was a partner in the Boston Belting Company. It is perhaps not a coincidence that Charles junior pioneered the use of rubber gloves by medical staff during surgery. All three boys graduated from Harvard (Henry in 1862, Charles in 1866, and John in 1869). John married Louisa Eldridge in 1878, and they had a daughter, May (or Mary) Ruth McBurney (1879-1947). May married William Howard Gardiner Jr. (1875-1952) in 1918, and on her death left an endowment to Harvard University to establish the Gardiner Professor in Oceanic History and Affairs to honour her husband. John worked for his father’s company and later in his own brokerage firm, Barnes, McBurney & Co; he died of tuberculosis.

Mary (or Mamie) McBurney married Dr Barthold Schlesinger (1828-1905), who was born in Germany of a Jewish ethnic background, and immigrated to the USA possibly in 1840, becoming a citizen in 1858. For many years, from at least 1855, he was a director of a steel company, Naylor and Co, the US subsidiary of leading steel firm Naylor Vickers, of Sheffield, UK. Barthold’s brother, Sebastian Benson Schlesinger (1837-1917), was also a director of Naylor & Co from 1855 to at least 1885; he was also a composer, mostly it seems of lieder and piano music; some of his music has been performed at the London Proms. At the time, Naylor Vickers were renowned for their manufacture of church bells, but in the 20th century, under the name of Vickers, they became a leading British aerospace and defence engineering firm; the last independent part of Vickers was bought by Rolls-Royce in 1999. Mary and Barthold Schlesinger appear to have had at least five children, Mary (1859- , married in 1894 to Arthur Perrin, 1857- ), Barthold (1873- ), Helen (1874- , married in 1901 to James Alfred Parker, 1869- ), Leonora (1878- , married in 1902 to James Lovell Little, c. 1875- ), and Marion (1880- , married in 1905 to Jasper Whiting, 1868- ). The Schlesingers owned an estate of 28 acres at Brookline, Boston, called Southwood. In 1879, they commissioned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead (1822-1903), the designer of Central Park in New York and Prospect Park in Brooklyn, to design the gardens of Southwood; some 19 acres of this estate now comprises the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, of the Greek Orthodox Church of North America. The Schlesingers were lovers of art and music, and kept a house in Paris for many years. An 1873 portrait of Barthold Schlesinger by William Morris Hunt (1824-1879) hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

While a student at Harvard, Henry H. McBurney was a prominent rower. After graduation, he spent 2 years in Europe, working in the laboratories of two of the 19th century’s greatest chemists: Adolphe Wurtz in Paris and Robert Bunsen in Heidelberg. Presumably, even Harvard graduates did not get to spend time working with famous chemists without at least strong letters of recommendation from their professors, so Henry McBurney must have been better than average as a chemistry student. He returned to Massachusetts to work in the then company, Boston Elastic Fabric Company, of his father, and then, from November 1866, as partner for another firm, Campbell, Whittier, and Co. From what I can discover, this company was a leading engineering firm, building in 1866 the world’s first cog locomotive, for example, and, from 1867, manufacturing and selling an early commercial elevator. Henry H. and Susan S. McBurney had three children: Mary McBurney (1867- , in 1889 married Frederick Parker), Thomas Curtis McBurney (1870-1874), and Margaret McBurney (1873-, in 1892 married Henry Remsen Whitehouse). Mary McBurney and Frederick Parker had five children: Frederic Parker (1890-), Elizabeth Parker (1891-), Henry McBurney Parker (1893-), Thomas Parker (1898.04.20-1898.08.30), and Mary Parker (1899-). Margaret McBurney and Henry Whitehouse had a daughter, Beatrix Whitehouse (1893-). The name “Thomas” seems to have been ill-fated in this extended family.

HH died suddenly in Bournemouth, England, in 1875, after suffering from a lung disease. As with any early death, I wonder what he could have achieved in life had he lived longer.

POSTSCRIPT (Added 2011-11-21): Henry H. McBurney’s visit to the Heidelberg chemistry lab of Robert Bunsen is mentioned in an account published in 1899 by American chemist, Henry Carrington Bolton, who also worked with Bunsen, and indeed with Wurtz. Bolton refers to McBurney as “Harry McBurney, of Boston” (p. 869).

POSTSCRIPT 2 (Added 2012-10-09): According to the 1912 Harvard Class Report for the Class of 1862 (see Ware 1912), Henry H. McBurney spent the year from September 1862 in Paris with Wurtz and the following year in Heidelberg with Bunsen. He therefore presumably just missed meeting Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1841-1880), son of composer Felix, who graduated in chemistry from Heidelberg in 1863. PM-B went on to co-found the chemicals firm Agfa, an acronym for Aktien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation. I wonder if Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy ever returned to visit Bunsen in the year that Henry McBurney was there.

POSTSCRIPT 3 (Added 2013-01-20): I am most grateful to Gerard McBurney for the portrait of Charles H. McBurney, and for additional information on the family. I am also grateful to Henrietta McBurney Ryan for information. All mistakes and omissions, however, are my own.

NOTE: If you know more about any of the people mentioned in this post or their families, I would welcome hearing from you. Email: peter [at] vukutu.com

References:

Henry Carrington Bolton [1899]: Reminiscences of Bunsen and the Heidelberg Laboratory, 1863-1865. Science, New Series Volume X (259): 865-870. 15 December 1899. Available here.

George Santayana [1944]: Persons and Places: The Background of My Life. (London, UK: Constable.) (New York, USA: Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

Charles Pickard Ware (Editor) [1912]: 1862 – Class Report – 1912. Class of Sixty-Two. Harvard University. Fiftieth Anniversary. Cambridge, MA, USA, Available here.

Footnotes:

1. Santayana writes as follows about Susan Sturgis Williams (Santayana 1944, page 74 in the US edition):

Nothing withered, however, about their sister Susie, one of the five Susie Sturgises of that epoch, all handsome women, but none more agreeably handsome than this one, called Susie Mac-Burney and Susie Williams successively after her two husbands. When I knew her best she was a woman between fifty and sixty, stout, placid, intelligent, without an affectation or a prejudice, adding a grain of malice to the Sturgis affability, without meaning or doing the least unkindness. I felt that she had something of the Spanish feeling, So Catholic or so Moorish, that nothing in this world is of terrible importance. Everything happens, and we had better take it all as easily or as resignedly as possible. But this without a shadow of religion. Morally, therefore, she may not have been complete; but physically and socially she was completeness itself, and friendliness and understanding. She was not awed by Boston. Her first marriage was disapproved, her husband being an outsider and considered unreliable; but she weathered whatever domestic storms may have ensued, and didn’t mind. Her second husband was like her father, a man with a checkered business career; but he too survived all storms, and seemed the healthier and happier for them. They appeared to be well enough off. In her motherliness there was something queenly, she moved well, she spoke well, and her freedom from prejudice never descended to vulgarity or loss of dignity. Her mother’s modest solid nature had excluded in her the worst of her father’s foibles, while the Sturgis warmth and amiability had been added to make her a charming woman.”

POST MOST RECENTLY UPDATED: 2013-03-26.