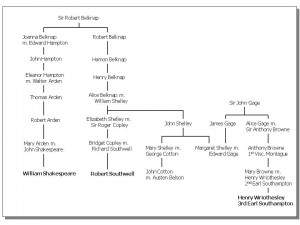

I have written before about Robert Southwell SJ, poet, martyr and Shakespeare’s cousin, and quoted some of his poems. Southwell (c. 1561-1595) was an English Jesuit from an aristocratic family, whose mother had been a governess and friend of Queen Elizabeth I. He left England illegally to study for the priesthood and returned — again illegally — to live and minister in secret to England’s oppressed Catholic population. He was captured, tortured by Elizabeth’s sadistic religious police, subjected to a show trial, and publicly executed.

Southwell was a poet of fine sensitivity, and drew on his Jesuit spiritual training to become the first English poet to develop personation (or subjectivity), a psychologically-real description of the interior self. His cousin Will Shakespeare was to adopt this idea in his poetry and plays, so that (for example) we learn about Hamlet’s internal mental deliberations, not only about his public actions and conversations. The late Anne Sweeney argued that Southwell developed personation in his poetry as a direct result of completing the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Lopez of Loyala, a process of meditation and self-reflection which all Jesuits undertake. In her words (p. 80):

The core experience of the Ignatian Exercises was the reading and learning of the hidden self, the exercisant learning to define his reponses according to a Christian morality that would then moderate his behaviour. After a powerfully imagined involvement in, say, Christ’s birth, he was required to withdraw the mind’s eye from the scene before him and redirect it into himself to analyse with care the feelings thereby aroused.”

It would be interesting to know if Ignatius himself drew on literary models from (eg) Basque, Catalan or Spanish in devising the Exercises.

Living underground and on the run, Southwell wrote poetry for a community unable to obtain prayer books or to easily hear preachers; poetry was thus a substitute for sermons and for personal spiritual counselling, and a form of prayer and spiritual meditation. His poetry is also strongly visual.

Because the Jesuit mission to England during Elizabeth’s reign was forced underground it is not surprising that Jesuit priests mostly lived in the homes of rich or noble Catholics, or Catholic sympathizers, sometimes hidden in secret chambers. It is more surprising that there were still English nobles willing to risk everything (their wealth, their titles, their freedom, their homeland, their lives) to hide these priests. One such family was that of Philip Howard, the 20th Earl of Arundel (1557-1595), who was 10 years a prisoner of Elizabeth I, refusing to recant Catholicism, and who died in prison without ever meeting his own son. Howard’s wife, Anne Dacre (1557-1630), was also a staunch Catholic. The earldom of Arundel is the oldest extant earldom in the English peerage, dating from 1138.

The Howard’s London house on the Thames was one of the noble houses which sheltered Robert Southwell for several years. The location of their home, between the present-day Australian High Commission and Temple Tube station, is commemorated in the names of streets and buildings in the area: Arundel Street, Surrey Street, Maltravers Street (all names associated with the Arundel family), Arundel House, Arundel Great Court Building, the former Swissotel Howard Hotel, and the former Norfolk Hotel (now the Norfolk Building in King’s College London) in Surrey Street. Maltravers Street is currently the location for a nightly mobile soup kitchen. Of course, in Elizabethan times the Thames was wider here, the Embankment only being built in the 19th century. One can still find steps in some of the side streets leading to the Thames descending at the edge where the previous riverbank used to be, for instance on Milford Lane.

Southwell also, it seems, spent time in the London house of his cousin Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624), who was also Shakespeare’s patron and cousin. Southampton’s house then was a short walk away, in modern-day Chancery Lane, on the east side of Lincoln’s Inn fields. Southampton was part of the rebellion of Robert Deveraux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1565-1601) against Elizabeth in February 1601. The London house of Essex was also along the Thames, downstream and adjacent to that of the Howard family. The street names there also recall this history: Essex Street, Devereaux Court.

Supporters of Essex, chiefly brothers of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland (1564-1632), paid for a performance of Shakespeare’s play, Richard II, the evening before the rebellion. Percy was married to Dorothy Devereaux (1564-1619), sister of Robert, and was regarded as a Catholic sympathizer. Percy also employed Thomas Harriott (1560-1621), a member of the matherati. Given the physical proximity of these noble villas, it is likely too that Southwell and Harriott met and knew each other.

And, weirdly, Essex and Norfolk are adjacent streets in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, too (close by and parallel to Orchard Street).

References:

The image is Shown a plan of Arundel House, the London home of the Earls of Arundel, as it was in 1792 (from the British Library). The church shown in the upper right corner is St. Clement Danes, now the home church of the Royal Air Force.

Christopher Devlin [1956]: The Life of Robert Southwell: Poet and Martyr. New York, NY, USA: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.

Robert Southwell [2007]: Collected Poems. Edited by Peter Davidson and Anne Sweeney. Manchester, UK: Fyfield Books.

Anne R. Sweeney [2006]: Robert Southwell: Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape 1586-1595. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.