Can a work of visual art be an argument? I believe the answer to this question is yes. In this and in some future posts, I will give examples, drawn from Australian Aboriginal art and from pure mathematics.

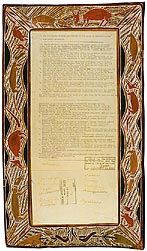

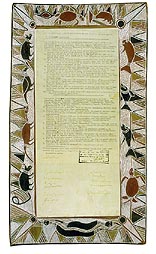

In August 1963, the Yolgnu people of Yirrkala (eastern Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory) petitioned the Australian Government for legal rights to traditional land. The petition was in the form of two painted bark panels. The argument for land rights was made in three ways — in English text, in Gumatj text, and in the surrounding art, which depicted the traditional relations between the Yolgnu people and their land. It is important to note that the visual images are not mere decoration of the text, but a presentation of the same argument in a different language, a visual language.

The artwork of the Yolngu Bark Petition (copied above) is a form of argument, for a claim asserting traditional rights to particular land. The reason that the artwork is an argument derives from the general nature of traditional Australian Aboriginal art, which presents a diagrammatic or iconic description of a particular geographic region, identifying the landscape features of that region (eg, rivers, hills, etc) along with the dreamtime entities (animals, trees, spirits) who are believed to have created the region and may still inhabit it. (The “dreamtime” is the period of the earth’s creation.) The art derives from stories of creation for the region, which are believed to have been handed down (orally and via artwork) to the current inhabitants from the original dreamtime spirits through all the intermediate generations of inhabitants.

Accordingly, the only people who have the necessary knowledge, and the necessary moral right, to create an artistic depiction of a region are those who have been the recipients of that region’s creation story. In other words, the fact that the Yolngu people were able to draw this depiction of their region is itself evidence of their long-standing relationship to the specific land in question. The existence of the art-work depicting the local landscape is thus an argument for their claim to ownership rights to that land. (Note that the art work’s role as argument arises primarily from the special nature of the claim it supports; the art is not, and could not easily be, an argument for any other kind of claim.)

In support of this position, I present some quotations, the first several as explanation for people unfamiliar with Australian aboriginal mythology and art.

Judith Ryan (1993, p. 50):

The term “Dreaming” is difficult for us to comprehend because of its use as noun and adjective in imprecise and ungrammatical ways to refer to the creation period, conception site, totem, Ancestral being, ground of existence, and the notions of supernatural, eternal or uncreated.”

Jean-Hubert Martin (1993, p. 32):

One can more or less imagine what “Dreaming” is: that link between the individual and his land, between the clan and its territory. The paintings [of Aboriginal artists] show figured spaces representing spaces both physical and mental, but it is difficult to go much further than that.

Following Aboriginal explanations one can recognise and name the various elements in these paintings. The thought structure, the references and the signifance of these words and fragments of speech – which reach us distorted by translation – still remain an enigma despite the valiant attempt to explain them in the ensuing texts. A not inconsiderable difficulty is posed by the mystery surrounding certain rituals and their formal depiction. And, one has to remember that what we see today of Aboriginal art is only that which we have been allowed to see.”

Ulrich Krempel (1993, p. 38) quotes C. Anderson/F. Dussart (1988, p. 18), as follows:

When asked about their paintings, [Australian Aboriginal] artists usually respond that the painting “means” or is “my country”, that is, it is a depiction of the painter’s territory. When queried further about the “Dreaming” story, the artist will often identify the main Ancestor depicted and perhaps the primary site at which the Ancestor undertook the actions portrayed in the painting. It is possible for an outsider, especially if working in the local language, to gain further insight into the narrative of events described in the painting, but even then access to the different levels of meaning may be restricted.”

Three quotations from Horward Morphy [1991]:

From a Yolngu perspective, paintings are not so much a means of representing the ancestral past as one dimension of the ancestral past . . .” (page 292)

Yolngu art also provides a framework for ordering the relations between people, ancestors, and land.” (page 293)

Paintings [in Yolngu society] gain value and power through their incorporation in such a process [of cultural definition], through being integral to the way a system (of clan-based gerontocracy) is reproduced, and through being part of its ideological support. Paintings gain power because they are controlled by powerful individuals, because they are used to discriminate between different areas of owned land, because they are used to mark status, to separate the initiated from the uninitiated and men from women. Their use in sociopolitical contexts creates part of their value. However, their value is also conceptualized in other terms, in terms of their intrinsic properties.” (page 293)

Janien Schwarz (1999, pp. 56-57):

In the first section, I argue that an understanding of the Bark Petitions is inseparable from an understanding of Yolngu relations to land. In Yolngu culture, the painting of designs is regarded as constructing an interface between the ground, its spiritual essence, and specific groups of people. The designs on the Petition are inseparable from these associations, in particular from the geographic locations at which they originated during Creation or wangarr. Putting the Petitions’ clan designs in a Yolngu cultural context reveals their strong artistic and political links to the Yolngu people and their land. With mounting pressures on land use from outsiders, Yolngu people have disclosed their designs (and inferred connections to land) through the context of art and art exhibitions as a political means of laying claim to their country which is under threat by bauxite mining. I present the Petitions as part of a larger history of Aboriginal people negotiating for land rights and cultural recognition through the production and presentation of painted barks and other objects of spiritual significance. . . . I contend that the painted motifs on the Bark Petitions merit interpretation as land claims and that, by extension, the paintings are a form of petition.”

References:

C. Anderson/F. Dussart: “Dreamings in Acrylic: Western Desert Art”. Catalog for Exhibition: Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. P. Sutton, Editor. Ringwood, Melbourne, 1988. p. 118.

Ulrich Krempel [1993]: “How does one read “Different” Pictures? Our encounter with the aesthetic product of other cultures”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 37-40.

Bernhard Luthi and Gary Lee (Editors) [1993]: Aratjara: Art of the First Australians. Exhibition Catalog. Dusseldorf, Germany: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Jean-Hubert Martin [1993]: “A Delayed Communication”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 32-35.

Horward Morphy [1991]: Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Judith Ryan [1993]: “Australian Aboriginal Art: Otherness or Affinity?”, in Luthi and Lee, pp. 49-63.

Janien Schwarz [1999]: Beyond Familiar Territory: Dissertation: Decentering the Centre. An analysis of visual strategies in the art of Robert Smithson, Alfredo Jaar and the Bark Petitions of Yirrkala; and Studio Report: A Sculptural Response to Mapping, Mining, and Consumption. PhD Thesis, Canberra School of Art, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Available from here.

0 Responses to “Art as argument”