This post is the latest in a sequence of lists of recently-viewed streamed TV and movies (in reverse chrono order).

- The Recruit (Season 2)

- Conclave (movie)

- Departure

This post is the latest in a sequence of lists of recently-viewed streamed TV and movies (in reverse chrono order).

Luca Guadagnino, director of the movie “Queer” (quoted in The New York Times, 20 November 2024):

Every movie is a documentary about the actor playing the character.”

The streaming series Young Royals, produced by Netflix Sverige, is a coming-of-age story about teenagers with the unusual feature that the main actors are themselves only teenagers. (Most series aimed at teenagers seem to employ actors in their twenties.) Because of this focus, the reviews of the series I have seen are aimed at parents deciding whether or not they should allow their teenage children to watch it.

This is a list of movies which play with alternative possible realities, in various ways:

- It’s a Wonderful Life [Frank Capra, USA 1947]

- Przypadek (Blind Chance) [Krzysztof Kieslowski, Poland 1987]

- Lola Rennt (run lola run) [Tom Tykwer, Germany 1998]

- Sliding Doors [Peter Howitt, UK 1998]

- The Family Man [Brett Ratner, USA 2000]

- Me Myself I [Pip Karmel, Australia 2000]

On the topic of possible worlds, this post may be of interest.

Man, in contrast to other animals, is conscious of his own existence. Therefore, conscious of the possibility of non-existence. Ergo, he has anxiety.”

Woman speaking at party, in Shadows, a film by John Cassavetes, 1959.

I am not convinced that man alone is conscious of his own existence, not when elephants go to specific places to die and other elephants avoid those places, nor when dogs play jokes on their owners, nor when octopodes exhibit an aesthetic sense, and nor when some birds seem to enter into relationships with humans to whom they present their offspring proudly as if to a grandparent.

I saw James Ivory’s film Slaves of New York soon after it appeared in 1989. The movie contains a scene set in a nightclub (minutes 63-69) with the most superb trance music, played by a male singer/guitarist and 3 female supporting musicians: one on percussion, one on synth, and a trumpeter. For most of this number, the trumpeter is smoking a cigarette, not playing, until near the end, when she plays while holding her smoking cigarette. The rhythm is a consistent, driving pattern: ta-ta-ta-ta daa daa (eg, 4 quavers followed by two crotchets) in each bar, or variants of this, with no changes of harmony, and drone-like chants over the top. The percussion includes a regular high-pitched woodblock (or similar).

I saw James Ivory’s film Slaves of New York soon after it appeared in 1989. The movie contains a scene set in a nightclub (minutes 63-69) with the most superb trance music, played by a male singer/guitarist and 3 female supporting musicians: one on percussion, one on synth, and a trumpeter. For most of this number, the trumpeter is smoking a cigarette, not playing, until near the end, when she plays while holding her smoking cigarette. The rhythm is a consistent, driving pattern: ta-ta-ta-ta daa daa (eg, 4 quavers followed by two crotchets) in each bar, or variants of this, with no changes of harmony, and drone-like chants over the top. The percussion includes a regular high-pitched woodblock (or similar).

Other than two songs by the combo of Arto Lindsay and Peter Scherer, this is the best music in the film (which apart from this music is forgettable). Unfortunately, this track is not on the official soundtrack, and the credits at the end of the film do not identify it clearly. The song is Mother Dearest, and the male singer (and the song’s composer) is Joe Leeway, formerly of British group, The Thompson Twins. It is a shame that he has not released any music under his own name, and no longer seems to be working as a muso. What a great loss to music.

One of my favourite films is Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948), which pitted John Wayne against Montgomery Clift. I came across an insightful review of the movie by Roderick Heath, here. The one aspect of the movie not mentioned in that review is the context in which the movie was made, immediately after World War II. At the time, the allies had large military forces being demobilized, with men – they were mostly men – returning with all deliberate speed to civilian life. Many of these men had played responsible and important roles in the war effort, roles requiring intelligence, personal initiative, courage, and the leadership of others. They returned to Civvy Street to find senior management posts occupied by the generation before them, and only subordinate roles available for themselves; they were often immensely frustrated. I once heard of a businessman’s club memorial dedicated To the Men Whose Sons had Given Their Lives in World War II, which sums up for me the self-regard of the elder of these two generations.

With this context in mind, I see Red River as a parable about the struggle between the two generations for the control of business and society in the post-war world. Clift’s caring and listening leadership style resonated much more with returning military men than Wayne’s deaf and inflexible approach, as it does also in the film with Wayne’s cattle drovers. In Japan and Germany, of course, the generation before had made a mess of things, and so there were greater opportunities in the post-war period for the next generation to take immediate charge.

From an article by David Bromwich about the movies of Howard Hawks:

The best actors of Hollywood films for three decades did a lot of their best work with Hawks. Grant and Bogart, pre-eminently, but also Cagney, Edward G Robinson, Hepburn (whom he introduced to screwball comedy), Barbara Stanwyck in Ball of Fire, Carole Lombard (who first showed her formidable power and comic range in Twentieth Century), and Montgomery Clift – a refined actor on the brink of being dismissed as overdelicate when Hawks gave him the second lead in Red River and offered tips on movement and gesture. For example, “the business”, as Hawks’s biographer Todd McCarthy relates, “of putting a strand of wheat in his mouth”; also “rubbing the side of his nose while in thought”. All the dynamic contest of that movie is there in the contrast between the voices of John Wayne and Clift, the loud monotone of command and the distinct but quiet utterance that suggests a reserve of conscience. All this Hawks must have heard at once and measured against the story when he saw the actors read for their parts.” (page 17, The Guardian Review, 2011-01-15)

It is hard to believe that someone who had been the leading male actor on the New York stage for a decade before he made his first film should have needed tips on movement and gesture, even from someone as great as Howard Hawks. Once again, Monty’s intelligence, contribution and agency seem belittled and minimized. Why is this, I wonder?

And, while we are wondering about his reception, why has Monty’s home city’s leading cultural magazine, The New Yorker, never published an article about him in its history?

Posts about Montgomery Clift can be found here.

Montgomery Clift is one of the silver screen’s greatest actors. I have written before about his intensely-naturalistic speaking style, with its pauses and false starts and mid-sentence hesitations and apparently improvised modifications on-the-fly. To speak as he did, in so many films, showed that this speaking style was probably not an artefact of all the screenwriters involved, especially when so few other actors in these or other films of the time spoke like that, but instead evidence of his own great intelligence and superb ear for speech.

Amy Lawrence has now written a fascinating book on his screen acting across his career, analyzing in detail what he did and how, and how he achieved his effects. By studying his own, hand-annotated personal copies of film scripts, for example, she is able to identify his particular contributions to the scripts and the dialogue of the films he acted in, and is able to demonstrate the artistry and diligence behind his naturalistic speech. And to show it, in many cases, as his personal artistry, as he worked to revise and rewrite dialog that was often originally stilted or unnatural.

By careful exegesis, Lawrence is also able to debunk some myths. Clift’s shambling, addled performance as a courtroom witness in the late Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), for example, is usually presented as evidence of the drug and alcohol addictions he is supposed to have succumbed to following his near-fatal car accident in May 1956. This accident destroyed his face and left him in pain, and led him to taking pain-killers and to drinking. But, as Lawrence demonstrates, his court-room appearance in the 1961 film shows many of the same personal characteristics and mannerisms of his court-room appearance in A Place in the Sun, filmed in 1951 – “tightening his fists, flexing his fingers, pushing against the armrests with his elbows” [Lawrence, p. 212]. Clearly, the origin of Clift’s witness-box performance is not drugs, but acting chops. Speaking of the character played by Clift in Nuremberg, she says:

Peterson’s gestures are emphatic, not neurotic, but combined with his broken syntax and repetition of sentence fragments, Clift clearly suggests in his performance that the character is not in control of himself. But the actor is. When we see the recurrence of these gestures across time and roles, before and after the accident, it seems reasonable to call them choices characteristic of the performer. Clift is not a mess; he plays one.” [Lawrence, p. 213]

Lawrence also notices how Clift, throughout his career, often acts with his back to the camera, either fully or partially. These episodes usually signal that he is engaged in some intense, interior, psychological reaction to some event or person, as if he could better tell us what he is thinking by not showing us his face. That he would even try to do something so counter-intuitive, let alone that he usually succeeds, demonstrates the great actor Clift was.

I had only one, very small quibble with Lawrence’s book. She describes (on page 63) the scene in The Big Lift (1950) when Clift’s character, about to receive an award for helping in the Berlin airlift, turns and sees for the first time that the official award-giver is a beautiful woman. Lawrence does not describe Clift’s eyes as he suddenly sees this woman: his pupils dilate widely as an expression of his character’s plain delight. We know of course, that the actor Clift must have practiced and rehearsed this dilation until he could undertake it at will. But knowing this fact increases our admiration for his acting skills, since it shows the dedication and diligence he brought to the task.

Clift’s acting art was artless, and like all artlessness, took immense preparation, intelligence, practice, and persistence to achieve.

Reference:

Amy Lawrence [2010]: The Passion of Montgomery Clift. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

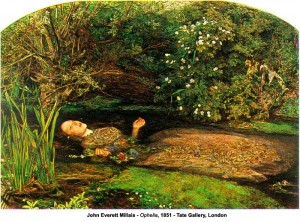

News today that an amateur art-historian, Barbara Webb, has identified the location which pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais used as background for his 1851 painting of the drowned Ophelia. The location is on the Hogsmill River at Old Malden in south London. It’s a long way from Elsinore.

The after-life of this image has been immense, at least in the English-speaking world. For instance, a print of the painting appears on the wall of the room rented by George Eastman, the humble protagonist of George Stevens’ 1951 movie, A Place in the Sun, a film of Theodore Dreiser’s novel, An American Tragedy. I took the presence of the print on Eastman’s wall not only as prophecy of the tragedy to come, but also as a reference to Hamlet, since Eastman, as he is played by Montgomery Clift, is undecided between his two lovers and the two very different fates which his involvement with them entails.