Norm’s latest entry in his Mommy and Daddy collection of songs is JJ Cale’s version of “Now, Mama don’t allow no guitar playing round here“. The version of this song that I first recall hearing was that of The Limeliters, who do not refer (as Cale does) to “My Mama“. So, I’d always understood the song to be about boarding-house owners, rather than natural-born mothers, and hence a fine metaphor for the suffocating nanny culture that was the US of the 1950s. I cannot find their version online.

Of course, a mention of The Slightly Fabulous Limeliters would be incomplete without a reference to their song about Harry Pollitt, long-time General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Author Archive for peter

Page 26 of 85

Recent Reading 8

The latest in a sequence of lists of recently-read books:

- Jason Matthews [2013]: Red Sparrow (New York: Simon & Schuster). A debut spy-thriller by a 33-year CIA clandestine service veteran, this book is well-written and gripping, with plot twists that are unexpected yet plausible. The book has placed the author in the same league of Le Carre and McCarry, and I recommend the book strongly. As so often with espionage and crime fiction, the main weakness is the characterization – the players are too busy doing things in the world for us to have a good sense of their personalities, especially so for the minor characters. Part of the reason for us having this sense, I think, is the sparsity of dialog through which we could infer a sense of personhood for each player. And the main character, Nate Nash, gets pushed aside in the second half of the book by the machinations of the other players. In any case, the ending of the book allows us to meet these folks again. Finally, I found the recipes which end each chapter an affectation, but that may be me. The author missed a chance for a subtle allusion with solo meal cooked by General Korchnoi, which I mis-read as pasta alla mollusc, which would have made it the same as the last meal of William Colby.

- Henry A. Cumpton [2012]: The Art of Intelligence: Lessons from a Life in the CIA’s Clandestine Service. (New York: Penguin). A fascinating account of a career in espionage. Crumpton reports an early foreign assignment in the 1980s in an African country which had had a war of liberation war, where the US had a close working relationship with the revolutionary Government of the country: The only candidates that seem to fit this bill are Zimbabwe or possibly Mozambique. Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF Government was so close to the USA in its early years that the Zimbabwe Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) had only two groups dealing with counter-subversion: a group seeking to counter South African subversion and a group seeking to counter Soviet subversion. Indeed, so great was the fear of Soviet subversion that the USSR was not permitted to open an embassy in Zimbabwe for the first two years following independence in 1980.

The book has four very interesting accounts:

1. Crumpton’s perceptive reflections on the different cultures of CIA and FBI, which are summarized in this post.

2. The account of the preparations needed to design, build, deploy, and manage systems of unmanned air vehicles (UAVs, or drones) in Afghanistan. The diverse and inter-locking challenges – technical, political, strategic, managerial, economic, human, and logistic – are reminiscent of those involved in creating CIA’s U2 spy-plane program in the 1950s (whose leader Richard Bissell I saluted here).

3. The development of integrated Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for tactical anti-terrorist operations management in the early 2000s. What I find interesting is that this took place a decade after mobile telecommunications companies were using GIS for tactical planning and management of engineering and marketing operations. Why should the Government be so far behind?

4. An account of CIA’s anti-terrorist programs prior to 11 September 2011, including the monitoring and subversion of Al-Qaeda. Given the extent of these programmes, it is now clear why CIA embarked on such an activist role following 9/11. George Tenet remarked at the time (in his memoirs) that such a role would mean crossing a threshold for CIA, but until Crumpton’s book, I never understood why this enhanced role had been accepted at the time by US political leaders and military leaders. From Crumpton’s account, the reason for their acceptance was that CIA was the only security agency ready to step up quickly at the time.

- Paul Vallely [2013]: Pope Francis: Untying the Knots. (London, UK: Bloomsbury). A fascinating account of the man who may revolutionize the Catholic Church. Francis, first as Fr Jorge Bergoglio SJ and then as Archbishop and Cardinal, appears to have moved from right to left as he aged, to the point where he now embraces a version of liberation theology. His role during the period of Argentina’s military junta of Jorge Videla is still unclear – he seems to have bravely hidden and help-escape leftist political refugees and activists, while at the same time, through dismissing them from Church protection, making other activitists targets of military actions.

Bergoglio seems to understand something his brother cardinals appear not to – that the Catholic Church (and other fundamentalist and evangelical Christian denominations) are not seen by the majority of people in the West any longer as places of saintliness, spiritual goodness, or charity, but as bastions of bigotry, irrationally opposed to individual freedom and to human happiness and fulfilment. In its campaigns against gay marriage rights, euthenasia, abortion, and other private moral issues, the Church opposes free will not only of its own clergy and lay members, but also of other citizens who are not even Catholic adherents. Such campaigns to limit the freedoms and rights of non-believers are presumptious, to say the least. The Catholic Church does a great deal of unremarked good in the world, work which is sullied and undermined by the political campaigns and bigoted public statements of its leaders.

The book is poorly written, with lots of repetition, and several chapters reprising the entire argument of the book, as if they had been stand-along newspaper articles. The author clearly thinks his readers have the minds of gold-fish, since interview subjects are introduced repeatedly with descriptions, as if for the first time.

The photo shows one of the demonstrations of the The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, held weekly since 1977 to protest the junta’s kidnap, torture, and murder of Argentinian citizens. We should not forget that the military regimes of South America, including the Argentinian junta of Videla, were supported not only by the Vatican and most local Catholic clergy (with some brave exceptions), but also by the US intelligence services, including during the administration of Jimmy Carter.

And the Romans? What did they ever do for us?

Andrew Sullivan takes down Maureen Dowd:

Obama’s political style is useless, apart from becoming the first black president, saving the US from another Great Depression, succeeding at getting universal healthcare, rescuing the American auto industry, presiding over a civil rights revolution, ending two failed wars, avoiding two doomed others (against Syria and Iran), bringing the deficit down while growing the economy, focusing the executive branch on climate change, and killing bin Laden.”

Influential Books

This is a list of non-fiction books and articles which have greatly influenced me – making me see the world differently or act in it differently. They are listed chronologically according to when I first encountered them.

- 2024 – Nikki Mark [2023]: Tommy’s Field: Love, Loss and the Goal of a Lifetime. Union Square.

- 2023 – Clare Carlisle [2018]: “Habit, Practice, Grace: Towards a Philosophy of Religious Life.” In: F. Ellis (Editor): New Models of Religious Understanding. Oxford University Press, pp. 97–115.

- 2022 – Sean Hewitt [2022]: All Down Darkness Wide. Jonathan Cape.

- 2022 – Stewart Copeland [2009]: Strange Things Happen: A Life with “The Police”, Polo and Pygmies.

- 2019 – Mary Le Beau (Inez Travers Cunningham Stark Boulton, 1888-1958) [1956]: Beyond Doubt: A Record of Psychic Experience.

- 2019 – Zhores A Medvedev [1983]: Andropov: An Insider’s Account of Power and Politics within the Kremlin.

- 2016 – Lafcadio Hearn [1897]: Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East. London, UK: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company Limited.

- 2015 – Benedict Taylor [2011]: Mendelssohn, Time and Memory. The Romantic Conception of Cyclic Form. Cambridge UP.

- 2010 – Hans Kundnani [2009]: Utopia or Auschwitz: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust. London, UK: Hurst and Company.

- 2009 – J. Scott Turner [2007]: The Tinkerer’s Accomplice: How Design Emerges from Life Itself. Harvard UP. (Mentioned here.)

- 2008 – Stefan Aust [2008]: The Baader-Meinhof Complex. Bodley Head.

- 2008 – A. J. Liebling [2008]: World War II Writings. New York City, NY, USA: The Library of America.

- 2008 – Pierre Delattre [1993]: Episodes. St. Paul, MN, USA: Graywolf Press.

- 2006 – Mark Evan Bonds [2006]: Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. Princeton UP.

- 2006 – Kyle Gann [2006]: Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice. UCal Press.

- 2005 – Clare Asquith [2005]: Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare. Public Affairs.

- 2004 – Igal Halfin [2003]: Terror in My Soul: Communist Autobiographies on Trial. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard UP.

- 2002 – Philip Mirowski [2002]: Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science. Cambridge University Press.

- 2001 – George Leonard [2000]: The Way of Aikido: Life Lessons from an American Sensei.

- 2000 – Stephen E. Toulmin [1990]: Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity. University of Chicago Press.

- 1999 – Michel de Montaigne [1580-1595]: Essays.

- 1997 – James Pritchett [1993]: The Music of John Cage. Cambridge UP.

- 1996 – George Fowler [1995]: Dance of a Fallen Monk: A Journey to Spiritual Enlightenment.

Doubleday. - 1995 – Chungliang Al Huang and Jerry Lynch [1992]: Thinking Body, Dancing Mind. New York: Bantam Books.

- 1995 – Jon Kabat-Zinn [1994]: Wherever You Go, There You Are.

- 1995 – Charlotte Joko Beck [1993]: Nothing Special: Living Zen.

- 1993 – George Leonard [1992]: Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment.

- 1992 – Henry Adams [1907/1918]: The Education.

- 1990 – Trevor Leggett [1987]: Zen and the Ways. Tuttle.

- 1989 – Grant McCracken [1988]: Culture and Consumption.

- 1989 – Teresa Toranska [1988]: Them: Stalin’s Polish Puppets. Translated by Agnieszka Kolakowska. HarperCollins. (Mentioned here.)

- 1988 – Henry David Thoreau [1865]: Cape Cod.

- 1988 – Rupert Sheldrake [1988]: The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Habits of Nature.

- 1988 – Dan Rose [1987]: Black American Street Life: South Philadelphia, 1969-1971. UPenn Press.

- 1987 – Susan Sontag [1966]: Against Interpretation. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- 1987 – Gregory Bateson [1972]: Steps to an Ecology of Mind. U Chicago Press.

- 1987 – Jay Neugeboren [1968]: Reflections at Thirty.

- 1985 – Esquire Magazine Special Issue [June 1985]: The Soul of America.

- 1985 – Brian Willan [1984]: Sol Plaatje: A Biography.

- 1982 – John Miller Chernoff [1979]: African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. University of Chicago Press.

- 1981 – Walter Rodney [1972]: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Overture Publications.

- 1980 – James A. Michener [1971]: Kent State: What happened and Why.

- 1980 – Andre Gunder Frank [1966]: The Development of Underdevelopment. Monthly Review Press.

- 1980 – Paul Feyerabend [1975]: Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge.

- 1979 – Aldous Huxley [1945]: The Perennial Philosophy.

- 1978 – Christmas Humphreys [1949]: Zen Buddhism.

- 1977 – Raymond Smullyan [1977]: The Tao is Silent.

- 1976 – Bertrand Russell [1951-1969]: The Autobiography. George Allen & Unwin.

- 1975 – Jean-Francois Revel [1972]: Without Marx or Jesus: The New American Revolution Has Begun.

- 1974 – Charles Reich [1970]: The Greening of America.

- 1973 – Selvarajan Yesudian and Elisabeth Haich [1953]: Yoga and Health. Harper.

- 1972 – Robin Boyd [1960]: The Australian Ugliness.

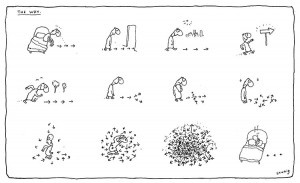

The Way

A recurring theme here has been the complexity of most important real-world decision-making, contrary to the models used in much of economics and computer science. Some relevant posts are here, here, and here. On this topic, I recently came across a wonderful cartoon by Michael Leunig, entitled “The Way” (click on the image to enlarge it):

I am very grateful to Michael Leunig for permission to reproduce this cartoon here.

Traffic safety for Zimbabweans

The Mail and Guardian newspaper of South Africa has compiled a list of prominent Zimbabwean politicians who have died in car accidents, here. Of course, there are other ways to die, as Rex Nhongo found.

Oral and written cultures at FBI and CIA

Henry Crumpton’s fascinating book about his time working for CIA includes an account of his time in 1998 and 1999 seconded, as a CIA liaison, to a senior post in the FBI. This account has a profound reflection of the cultural differences between the two organizations, differences which arise from their different primary missions: for FBI, the mission is to solve criminal cases (which is essentially a backwards-looking activity played against a suspect’s lawyers) versus, for CIA, the identification and avoidance of potential threats (which is inherently forwards-looking and played for an intelligence client). Crumpton summarized his reflections (contained on pages 112-115 of his book) in a Politico op-ed column here:

First, the FBI valued oral communications as much as or more than written. The FBI’s special-agent culture emphasized investigations and arrests over writing and analysis. It harbored a reluctance to write anything that could be deemed discoverable by any future defense counsel. It maintained investigative flexibility and less risk if its findings were not written — or at least not formally drafted into a data system. Its agents were not selected or trained to write.

This is also tied to rank and status: Clerks and analysts write, not agents. Agents saw writing as a petty chore, best left to others.

In contrast, most CIA operations officers had to write copiously and quickly. To have the president or other senior policymakers benefit from clandestine written reports — that was the holy grail. CIA officers prized clear, high-impact written content.

The second major difference between the FBI and CIA was their information systems. The FBI did not have one — at least one that functioned. An FBI analyst could not understand a field office’s investigation without going to that office and working with its agents for days or even weeks. With minimal reporting, there was no other choice.

CIA stations, in contrast, write reports on just about everything — because without written reports, there was no intelligence for analysts and other customers to assess. The CIA required high-speed information systems with massive data management, and upgraded systems constantly.The third difference was size. The FBI was enormous compared with the CIA. The FBI personnel deployed to investigate the East Africa bombings, for example, outnumbered all CIA operations officers on the entire African continent. The FBI’s New York field office had more agents than the CIA had operations officers around the world. The FBI routinely dispatched at least two agents for almost any task. CIA officers usually operated alone — certainly in the development, recruitment and handling of sources.

A fourth difference was the importance of sources. While both the FBI and the CIA placed a premium on a good source, the FBI did not actively pursue them beyond the context of an investigation. The agents would follow leads and seek a cooperative witness or a snitch, often compelled to cooperate or face legal consequences.

FBI agents seldom discussed sources. When they did, it was often in derogatory fashion. But they discussed suspects endlessly. That was their pursuit. And for the FBI, sometimes sources and suspects were one and the same.

CIA officers, on the other hand, routinely compared notes and lessons learned about developing, recruiting and handling sources — though couched so that specifics were not revealed. Ops officers’ missions and their sense of accomplishment, even their professional identity, depended on the success of sources and the intelligence they produced. FBI agents wanted evidence and testimony from witnesses that led to convictions and press conferences.

A fifth difference was money. The FBI had severe limitations on how much agents could spend and how they could spend it. The process to authorize the payment of an informant or just to travel was laborious.

As a CIA officer, however, I routinely carried several thousand dollars in cash — to entertain prospective recruitment targets, compensate sources, buy equipment or bribe foreign officials to get things done. I usually had to replenish my well-used revolving fund every month.

When I told FBI agents this, they seemed doubtful that such behavior was even legal. I often had to explain that the CIA did not break U.S. laws — just foreign laws.

Sixth, the FBI harbored a sense that because it worked under the Justice Department, it had more legal authority than the CIA. Some, after a few drinks, expressed moral objections to the CIA’s covert actions. I would argue that covert action, directed by the president and approved by congressional oversight committees, is legal. But somehow the notion of breaking foreign laws seemed less than ideal to some of my FBI partners.

Seventh, the FBI loved the press and worked hard to curry favor with it. For the CIA’s Clandestine Service, the media was taboo. Most of us had experienced occasions when media leaks undermined operations. Sometimes, our sources died because of this coverage. On top of that, we felt that the media seemed intent on portraying the CIA in a negative light. A CIA operations officer avoided the press like the plague.For the FBI, it was the opposite. Positive press could help fight crime and boost prestige and resources. Every FBI field office worked the media.

Eighth, the FBI collected evidence for its own use, to prosecute a criminal. The CIA primarily collected intelligence for others, whether a policymaker, war fighter or diplomat. The FBI, therefore, lacked a culture of customer service beyond the Justice Department. Without a customer for intelligence, the CIA had no mission.

Ninth, the FBI’s field offices, especially New York, acted as their own centers of authority, even holding evidence, because of their link to the local prosecutor. A city district attorney and civic political actors had great influence over an investigation.

The CIA station instead had to report intelligence to Langley, because the incentive came from there and beyond — particularly the White House.

Tenth, the FBI worked Congress. Every FBI field office had representatives dedicated to supporting congressional delegates. The FBI also had the authority to investigate members of Congress for illegal activity. So the bureau had both carrots and sticks.

But the CIA, particularly the Clandestine Service, had minimal leverage with Congress. Most CIA officers engaged Congress only when required to testify.”

The consequences of these differences for us all are immense. Crumpton again:

The FBI is still measuring success, according to one well-informed confidant, based on arrests and criminal convictions — not on the value of intelligence collected and disseminated to its customers.

When I served as U.S. coordinator for counterterrorism, from 2005 to 2007, I was a voracious consumer of intelligence. Yet I never saw an FBI intelligence report that helped inform U.S. counterterrorism policy. Has there been any improvement?”

Reference:

Henry A Crumpton [2012]: The Art of Intelligence: Lessons from a Life in the CIA’s Clandestine Service. (New York, NY, USA: Penguin Books).

Bellevue WA

The Tap House Grill, Bellevue, WA.

Jenny Biggar RIP

This is a belated tribute to long-time acquaintance, Jenny Biggar (1946-2008), for many years the Treasurer of the Budiriro Trust, a British-Zimbabwean educational charity. I found the following obituary, written by Ann Young and published in the Loddon Reach Parish Magazine (July/August 2008, 1 (4): 16).

Jenny Biggar died on May 8th [2008] after a valiant fight against Lymphoma. All those who packed into St. Mary’s church for her funeral on May 19th bore witness to a life that had been well lived and truly Christian. It was a wonderfully uplifting service and a tribute to someone who had touched the lives of others, not only here, but across the world, and whose dying had been an example for us all.

Jenny was brought up at Manor Farm in Grazeley and attended the Abbey School in Reading. She was the middle child with two older brothers and two younger sisters. Family life was always central to her so it seemed natural that, when her mother died, she returned to the Farm in 1985 to look after her father and make a home for him. She had spent many years working in Africa, had read English as a mature student and was embarking upon a D.Phil at Oxford when she felt called back to her family. She quickly became a very active member of the Parish with jobs ranging from P.C.C. Secretary, to making curtains for the Church hall. She also worked hard for her two favourite charities – The Budiriro Trust (which maintained her links with Zimbabwe) and the B.R.F. She did some counselling work at the Duchess of Kent House and worked in the Estate Office at Englefield Estate.

Jenny was a wonderful cook and will be remembered for her soup at many Church events. She was a skilled needle woman and an accomplished musician, singing with the Farley Singers, the Dever Singers and the Church choir as well as playing the organ. She was also an intellectual with a deep love of literature. She was honest and forthright in her opinions, but always with grace and good humour. Throughout her life Jenny had more than her fair share of difficulties; she fought hard battles to overcome them and developed not only a stoical resistance to pain and discomfort, but huge inner strength. She gave so much to us all and will be sorely missed.”

And here is an obituary by Elspeth Holderness (1923-2009) in the 2007-2008 annual report of the Budiriro Trust.

Jenny Biggar died on 8th May 2008 after a valiant fight against Lymphoma. She was a very wonderful and exceptional person. St. Mary’s Church, Shinfield, was packed for the inspiring Funeral Service, which included several choirs which Jenny used to sing in herself – a wonderful tribute to someone who had so many friends here and abroad and who was always cheerful and quietly helpful and who had this deep inner strength.

Until not long ago, Jenny was a Trustee of Budiriro as well as Secretary and Fund-Raiser. She spent a great deal of time and energy in seeking out sources of funding, both from individuals and corporate bodies and managed to raise thousands of pounds with her tireless energy and enthusiasm. She was also involved in other ways (not least her home-made cakes, etc. after each Annual Meeting!). She was working at Manor Farm Estate, and also did some counselling.

She grew up at Manor Farm, run by her father, on the Englefield Estate, near Reading, and was part of a big, loving family. Her father, Bill, and Hardwicke [Holderness] (see obituary, Budiriro Trust Annual Report 2006-2007), had become great friends during the Second World War in the same squadron in RAF Coastal Command, and years later we found him and his family again on one of our rare visits to Britain – which was lovely. Around 1970, Bill wrote and said Jenny had decided to emigrate to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and could we perhaps “keep an eye” on her and we said “fine”.

She was, I think, very happy, working as a Medical Secretary, making new friends, joining St. Andrew’s Church [Salisbury], having her own flat, and also having the freedom of our house and garden. She also realised how some of the children around us needed education and to be able to read books. Jenny had a love of literacy and books and literature all her life.

After she rejoined her family some years later, she took a degree in English as a mature student at Reading University, and when we later went to live in Oxford, she had embarked on a DPhil at Oxford University, also in English. We introduced her to Ken and Deborah Kirkwood (who had been highly involved in Budiriro since the beginning and had already embroiled both of us), and she was happy to become involved too. She worked miracles.

Elspeth Holderness was the wife of Hardwicke Holderness (1915-2007), RAF pilot, Rhodesian MP and fighter for racial equality, whom I mentioned here.

The Yirrkala Bark Petition

Australia has just commemorated the 50th anniversary of the presentation of the Yirrkala bark panels as a petition to the Australian Commonwealth Parliament in August 1963. The panels are an example of visual art as argument, as I noted here.

Related posts on visual arguments here and here.